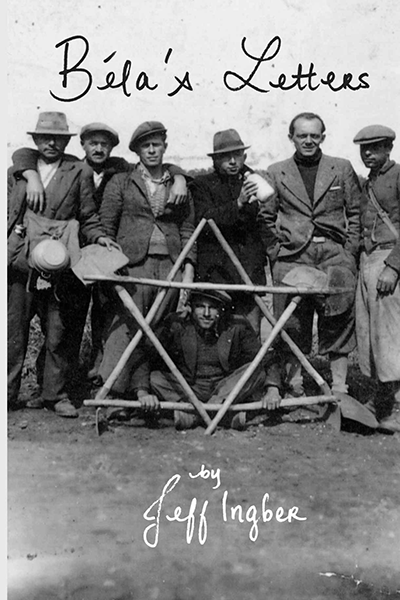

Bela’s Letters

Bela’s Letters

Critique by Ellen LaFleche

Critique by Ellen LaFleche

In Béla's Letters, Jeff Ingber, the son of Jewish Holocaust survivors, has written an epic novel that is girded by a real-life treasure trove of letters written by his ancestors before and during the Holocaust.

I love books that teach me not only facts but new ways of interpreting and emotionally understanding issues. I enjoyed learning about Munkács, a former Hungarian/Czech city now a part of Ukraine. The book is well researched with rich details about the Carpathian Mountain Range and its notoriously long winters, family recipes and customs. Both Jendi and I greatly appreciated the philosophical and religious questions that were debated throughout the book. The tension built up chapter by chapter, bringing great urgency to the very frequent discussions about why Ingber's ancestors decided to leave or stay in Europe during Hitler's rise to power.

Ingber's clear and calm prose highlighted the horrors of the Holocaust without gratitious descriptions of violence. For example, here is a character trying to find information about a missing relative:

I spotted a young woman in uniform, her thick brown hair pulled back into a smooth twist at the nape of her neck, sitting on a chair sifting through a file cabinet...

I summoned the language of my early schooling and addressed the woman in Russian.

"Excuse me—may I ask you a question?"

She turned toward me, revealing wide cheekbones and a heart-shaped face marred by a web of pimple scars, and smiled. "Visitors need to sign in on the second floor," she blurted out.

"Please, we're trying to find family members."

The woman muttered, "As I said," pointing in the air.

Her words did not sting so much as the sight of her turned back.

The simplicity of this passage makes it so emotionally effective.

I also appreciated the skilled, error-free writing. As mentioned in our judging comments, proofing errors were a major problem in many entries this year. I do feel that at 572 pages, Béla's Letters was too long and could have benefitted from a 25 percent editing reduction. The physical book itself was so heavy and cumbersome it was hard to read comfortably.

I was fascinated by Ingber's discussion about the challenges faced by the woman who translated the letters from Hungarian into English. The chapter introducing the letters explored the linguistic, historical and cultural issues that had to be taken into account during translation. I was disappointed that the author did not use more of the letters. The first hundred or so pages did not include the letters; the narrative gained strength as the letters became more frequent. The literary technique itself—writing a fictional account bookended by actual documents—was innovative; I wish the book had pushed that technique a bit more.

This book stayed with me long after I finished it—a sure sign of skilled storytelling. It is an important addition to the history of the Holocaust. I feel honored to have had the chance to evaluate this book.