The Tell

The Tell

Linda I. Meyers' The Tell, a feminist memoir and family history, is a stellar example of how to turn eight decades of life into a taut narrative without filler or digressions. Culturally reminiscent of graphic novelist Will Eisner's sagas of New York City Jewish immigrant life, The Tell includes celebrity cameos by Woody Allen and Ralph Lauren (born Lipshitz) as well as the less glamorous but heroic work of breaking inherited trauma patterns.

The suicide of Meyers' depressed mother when the author was 28 catalyzed her to change her life. She left a stifling marriage, began college, shepherded her three sons through a show business career, and became a psychologist and psychoanalyst. The road was never smooth, as she was romantically drawn to unreliable men on the pattern of her father, a charismatic small-time Brooklyn racketeer. The women's movement of the 1970s gave her a framework to understand the constraints that had warped her family's emotional development. As for the book's title, I will simply quote her eloquent foreword:

A tell is an unconscious reveal given under psychological stress. The poker player who recognizes an opponent's tell, perhaps the twitch of the eye or the soft intake of breath, is best situated to win the game or, at the least, to mitigate her losses. A tell is also an archaeological mound containing the accumulated remains of human occupation and abandonment over many centuries. And a telltale or tattletale is a child who reports others' wrongdoings or reveals their secrets.

This memoir is a tell in all of its meanings. It is a compilation of standalone essays that together trace my journey out of the tell my family inhabited and through the restrictive and chauvinistic culture of the forties and fifties, towards emancipation and self-realization.

First-round screener Annie Mydla said, "One of the reasons I value this book so highly is that in The Tell, I recognize the literary memoir that so many of our critique clients and North Street entrants are trying to write." Every year, we receive numerous linear, slice-of-life, full-lifespan memoirs that don't approach this level of thematic unity, to the point that we've been advising first-time creative nonfiction authors to narrow their topic to a pivotal event.

How did she make it work? Meyers explains in the foreword: "I have selected only those episodes from my life that I believe to be turning points and best tell this story; therefore, large sections of time are intentionally left out."

The Winning Writers judges are in this business because we're avid readers, and as such, we all have our special interests. Judging 2,000 diverse books pushes us to expand beyond the typical genres and topics we seek out for leisure reading. The flip side is that when a book does resonate with one of us for personal reasons, we take extra care to be objective about its other qualities.

All that is to say, I can't deny this book made an extra impact on me because I grew up in the world Meyers writes about so vividly. Born in the early 1940s, she's a contemporary of my recently deceased biological mother, who was also the descendant of working-class Jewish immigrants from the Lower East Side, a product of the same pressures on intelligent women to subjugate themselves to marriage and motherhood while being the unacknowledged foundation of the household. Loneliness, neurosis, and emotional withdrawal from their children often afflicted women like her mother and my grandmother, compounded by the social permission for their husbands to be charming and feckless men about town, detached from domestic emotional labor.

The diction of Meyers' characters, with their sprinkling of Yiddish words and immigrant syntax such as "I want you should do this" or "He doesn't know from that," brought back the sounds of my childhood. Whether this is your world or not, I believe her skill in re-creating it will fascinate you, too.

The Tell is deeply satisfying because Meyers took charge of her healing in a way that many inheritors of intergenerational damage never do. She summarizes the family dynamics with clarity and empathy, but neither moralizes about forgiveness nor dwells in bitterness.

As both a liberating cultural touchstone for Jewish Boomers and a problematic symbol of male entitlement, Woody Allen is a perfect supporting character for Meyers' self-transformation into a different kind of woman than her ancestors. Her three young sons were getting regular work as commercial actors and models when Allen picked one of them to co-star in Annie Hall. But that was it for their show business career. Rather than try to build on this celebrity, she heeded her kids' desire for a normal life going forward. This episode for me exemplified Meyers' progress, both in breaking her family pattern of using children to meet their mothers' unfulfilled needs, and in the opportunities that feminism made available to her generation.

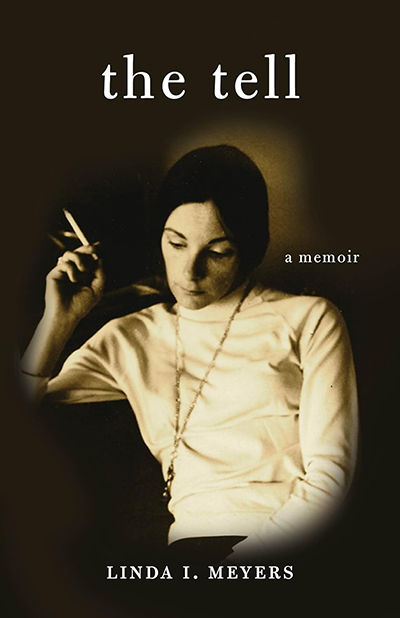

The physical book from well-regarded hybrid publisher She Writes Press was a sturdy trade paperback with a professional interior layout, attractive chapter headings, and well-chosen archival family photographs that hinted at the characters' yearnings, charisma, and sorrows. The sepia-on-black cover with a 1970s-style photograph of a pensive woman holding a cigarette (shades of Susan Sontag!) perfectly conveyed that this is a book about a woman of a certain generation, literary and full of interiority. You wouldn't guess that it was not from a Big Five publisher. Read it and be moved.

Read an excerpt from The Tell (PDF)

Buy this book on Amazon.