Otter St. Onge and the Bootleggers

Otter St. Onge and the Bootleggers

Critique by Jendi Reiter

Critique by Jendi Reiter

In the introduction to Otter St. Onge and the Bootleggers, Alec Hastings says this "rollicking tale of adventure" was inspired by the storybook heroes of his boyhood—Robin Hood, the Hardy Boys, Huck Finn, and the like. The novel pays homage to those sprawling, colorful yarns while updating them for modern sensibilities. Otter's sweetheart Mary is an action heroine in her own right, with a traumatic backstory that would have been taboo for young readers of yesteryear.

Our likeable narrator, Otter, is an 18-year-old orphan who helps his grandfather run bootleg whiskey on Lake Champlain in the 1920s. When they discover clues that his father, an army sergeant who went missing in a World War I battle, might still be alive, Otter and his boisterous relatives embark on a hair-raising journey to find him before his mortal enemy gets there first. Though lacking in formal education, Otter thinks deeply about his place in the world and has a soul that is stirred by the beauties of nature. As judges, we thought that his voice gave literary depth and poetry to the saga, while remaining believable for his age and milieu.

The physical descriptions of setting and bodily sensations were vivid and absorbing. People really got hurt in the fight scenes and needed time to recover. I felt I was right there in the rainstorms, night-time sieges, and boat wrecks. Kudos to Hastings for choosing a time period and location that haven't been used too often in historical fiction. It certainly stood out among our entries.

Hastings relies on two old-fashioned literary devices, the story-within-a-story and the dramatic coincidence, to enhance this novel's period feel. These can be off-putting at first for readers who expect realistic dialogue and the illusion that events "just happen" without an author pulling the strings. I enjoyed the narrative digressions but felt that one coincidental connection between the major characters would have been enough. The stories they told turned out to be relevant to the main plot, but sometimes the revelation came so late that I had to flip back to the early chapters to retrieve the reference.

Some of the minor characters could have been cut to make the plot easier to follow, especially at the beginning. Luc, Little Roy, and Louis all showed up in the same boat, had similar names, and didn't play a key role in the action. To add to the confusion, there's also a Lucien who shows up later as one of Otter's father's sidekicks. Another of the sidekicks is named Angus, too similar to grandfather Amos. I could never figure out whether Petrice was a housekeeper or a relative. My co-judge Ellen LaFleche felt even more could be done to put the female characters on an equal footing; it seemed to her that women were always introduced in scenes where they served food to men.

To make this book more accessible for young adult readers, Hastings could shorten it by cutting a couple of the fight and chase scenes, and shortening the story-within-a-story passages. If these anecdotes were told with fewer details than the main narrative, they would be easier to distinguish from the flow of the action.

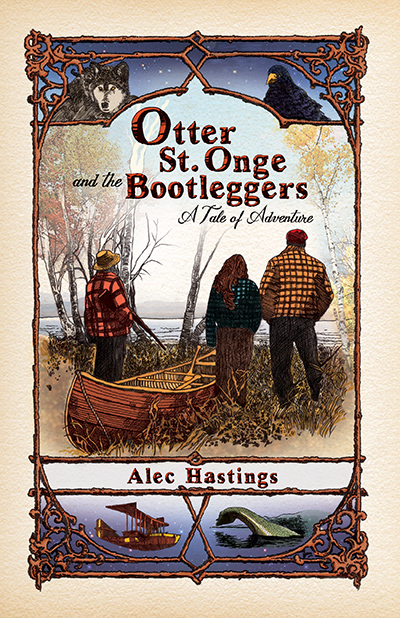

Carrie Cook's original cover illustration and chapter headings (each began with a drop cap illustration of a moonshine jug) were a delightful nod to classic storybooks. It reminded me of the distinctive design of the Harry Potter books. Unfortunately, in the print edition from The Public Press, the covers were printed on cheap cardstock that fell off when the judges shared the book around. Fixing this one flaw would produce a handsome book that stands up to re-reading and does justice to the richly textured, exciting tale within.