Return to Heartwood

Return to Heartwood

The elegant, subtle "tree portraits" in William Guion's Return to Heartwood: A Search for the Heart of Live Oak Country represent his 40 years of photographing and researching Louisiana's oldest specimens of this iconic Southern tree. Quercus virginiana is colloquially known as "live oak" because it sheds and replaces leaves all year round, rather than losing its leaves in the winter like most deciduous tree species. In Guion's writing, the name takes on another level of meaning. He invites us to build relationships with trees as individuals who have their own spirits and emotions.

The South's venerable trees bear the weight of atrocities they have witnessed on former slave plantations, a history that the author does not gloss over. Elite families were able to cultivate and preserve these trees because of wealth extracted from Black bodies. The task of current-day live oak conservationists is to advocate for the value of local history without romanticizing the antebellum era. At times even Guion slips up in this way, by referring to the first Europeans in the region as "settling" rather than "colonizing" the land. "Settler" erroneously implies a previously unused land, empty of people.

Guion writes eloquently about photography as a meditative process. Using an old-fashioned manual view camera with 4x5-inch negatives, with shots that could take 45 minutes to stage correctly, he created misty, spectral black-and-white images of huge spreading branches draped in Spanish moss. The portraits seem halfway between photos and meticulous pencil sketches, or perhaps 19th-century landscape etchings. This technique gives his subjects the aura of ghosts reaching across time to beckon us into their troubled history—as well as warning us about the loss of irreplaceable flora to pollution and urban development.

In a photo book with a single subject, especially in black-and-white, there is a risk of dullness from too little visual variety. The second half of Return to Heartwood was stronger in this respect, with more different angles and settings for the trees being profiled.

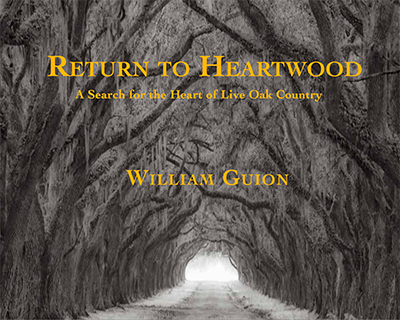

The book design was sturdy, on luxurious matte paper, with a glossy cover and strong binding. The cover photo was a tunnel of oaks leading to a luminous archway, a perfect invitation to open the book. The font had an old-fashioned, copperplate feel to it, appropriate for the subject matter, though the way it handled hyphens and dashes was visually confusing. There were some typos, mostly relating to punctuation. All in all, Return to Heartwood is a beautifully designed and thoughtful book with a unified vision. It would be equally at home on a conservationist's bookshelf and on the bedside table in a Southern bed-and-breakfast.