Rosebush and Why He Chuckled

Rosebush and Why He Chuckled

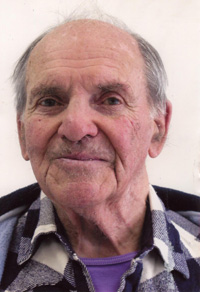

Rosebush was a born buccaneer, with wit, a Xhosa like Nelson Mandela, speaking its ringing tongue-clicks. He was tall, slim, beautifully built, with fine frank features.

Rosebush knew violence, with scars across his left stomach and thighs. He would happily show them, silvery weals on smooth chocolate, acquired in his Black Township of Khayelitsha, Cape Province. It housed a million, mainly Xhosa. The apartheid government had sited it well away from Cape Town city, rail return 9 Rand, then 75 pence, a sixth of a daily wage. Khayelitsha bulged with shacks of corrugated iron, wood, cardboard. It lacked running water, electricity, sewers. And security. Apla had stabbed and robbed Rosebush, he told us, because he wouldn't join them. Apla was the militant wing of the Pan-African Congress, its slogan One Settler One Bullet, fiery rivals of Mandela's ANC. They'd left Rosebush for dead.

Groote Schuur's Trauma Unit saved him. A squad roved the Peninsula by night for casualties. On a Saturday night that unit treated some 130 Blacks and Coloureds, almost all stabbings. Even with heart wounds, a favourite, the medical teams deftly saved 95%, provided they still breathed on arrival. So Rosebush had trotted briefly round the Trauma Unit's corridors. A glass tube, taped into his lung wound, discharged into a jar. Races between such walking wounded, their jars like jockeys, were popular. Rosebush got well fast. He had to feed two sons in Khayelitsha, and a wife and a younger son in the Transkei, 700 miles north-east, where (he said) she ran their tiny farm and sent the son to a mission school.

Why Rosebush? Well, a white Baas had so nicknamed him. Our old gardener, retiring, had sent him. We, in Rondebosch under Table Mountain, saw through our inner front door's fronted glass that he was Black. So did Samantha, our semi-Staffordshire bull-terrier. She barked hysterically. Before us, she'd been tied up in a Poor White's blazingly hot concrete yard, for which illogically Samantha hated Blacks—but not Rosebush! We opened to him, I holding her firmly. But Samantha simply dissolved, her ears laid back, wagging her seat off, eyes ecstatic, black lips parted wantonly!

"Rosebush!" he announced, standing lithe and neat, khaki bush-shirt immaculate, shorts knife-edged. He smiled, trusting, respectful, quite pleased about it.

"Kulungile," I replied. It meant OK, splendid.

He looked surprised, but answered courteously in Xhosa, sensing my slim command of it, then went on in fluent English. "I seek work, Baas. I've a wife and sons to feed."

Invited, he sat primly on parade in our sitting-room. "No tea or coffee, thank you! Just water." He passed us a reference from a lady in Hermanus: "Excellent gardener. Good-tempered, charming. Has taking little ways."

We engaged him promptly. He'd come every Wednesday from 8 am to 5 pm, with an hour off for lunch, which we'd provide, with breakfast, so he'd get at least two good solid meals a week. We'd pay him a more than competitive 80 Rand a day, plus his rail fares. He beamed and left.

Flowers bloomed at Rosebush's touch. He sang to them in Xhosa. Neither Soozi, a physiotherapist, nor I, a writer, had green fingers. Rosebush particularly prized our lawnmower. He could start it at once—I never could!—then drive it chuckling infectiously. Our lawns became shaven slick. We were delighted. There was only one racial flaw. Our Coloured char, Gertrude, had been with us 20 years. She came on Wednesdays too, and cooked. She used our inside toilet near the kitchen, as a perk, as had our former gardener, also Coloured. But, said she, how DARE Rosebush use it too? A Black! With what diseases? So Rosebush was demoted to the other loo in the garden. He'd resent that, however quietly. The Whites had no monopoly of racism in South Africa. The big Coloured community could be as aloof, calling the Africans a Swart Gevaar, Black Peril. But any retaliation by Rosebush would be subtle.

His first year he came precisely every Wednesday, worked hard, chuckled merrily, ate heartily. He always left his loo spotless. In his second year we missed a few things, gold cufflinks, silver bracelets, cash. Sometimes the jewel resurfaced weeks later. Had it ever really gone? The cash never all disappeared. Only two out of say twenty 10-Rand notes lacked. But hadn't we perhaps miscounted beforehand? Rosebush's fine open features always smiled at us, helping with my fractured Xhosa, improving our garden, chuckling contagiously, ever charming, as the reference lady had said. Could we cynically have read more into her phrase "has taking little ways"? But she was untraceable after Hermanus. So our suspicions stayed muted.

And Samantha still adored Rosebush. She had her own exit, through a tunnel set in the back verandah wall. Plus middle-aged spread. she still slotted quite easily through it. She ejected from it like a bullet when she heard Rosebush arrive each week, her ears and thin black lips stretched back ecstatically. Our thefts never occured on a Wednesday, but usually once a month when Samantha and I were on her 40-minute constitutional. If, after it, she nosed about swooning, then something was gone. Yet I always locked up carefully. Still, someone who knew our movements perfectly had certainly got in. At times I'd even seen a Black outside, but too far off to recognize.

This shadowplay could have lasted forever, had Rosebush not sent his younger Khayelitsha son back to the Transkei for Its mission schools, far better than the Cape's state schools, always shut by the police in crises. So his eldest son had no steady education. His was a lost generation, doomed to unemployment and crime. Rosebush got his son's travel money from the Township's loan sharks at 30% a week. Repayment needed a big steal. Rosebush chose my 24-carat gold ring, its rampant-lion crest my matemal grandfather's. An Irish surgeon, he'd typically fought in the Boer War against the British. Our sitting-room photo showed him mounted and bush-hatted as The Terror of Van Tonder's Horse. I'd dangled the ring. Rosebush took it then panicked, so he told the Wynberg magistrate. His eldest son brought it back next morning, Thursday. Rosebush said he'd found it on the lawn at 5 pm. We and Gertrude were out, and he'd not dared to hide it. We'd dropped It, right? We were delighted. Was Rosebush OK?

"Knifed again last night," replied the youth, with aplomb.

We were horrified. "Was he still alive?"

"In bed," said his son, who clearly found such knifings old hat. Soozi rang and delayed her patients. We took Rosebush's son and drove past Muizenberg's fantastic wide beaches beyond which lolled the Great White Shark. Khayelitsha was as deadly, with jagged pondokkies, huts of tin and plywood, every crevice filled. Rosebush's shack was 5 metres by 4, two tiny rooms, a kitchen with primus, no toilets or running water. Rain would honeycomb it. Rosebush survived in a camp bed, right thigh bandaged. He beamed. "At my door last night," he said. "I refused him money. So he knifed me and fled."

"Shall I fix that bandage?" asked Soozi.

"Please don't touch it!" he replied immediately. "I've used lint, iodine!" Of course we left it. I thanked him for guarding our ring. We were impressed by his selflessness and good temper. He'd survive. He had bread, mealie meal, milk, tea, coffee, that impassive eldest son, who escorted us to our car. The bystanders eyed us sullenly, the mouths of their small kids tiny circles. We could have been aliens from outer space. Well, we'd sat on them for some 350 years.

Rosebush was back next Wednesday, wearing slacks. Full of smiles, he seemed fine. In fact, the loan-sharks were squeezing. Next day, back from our walk, Samantha and I were surprised. Inside, Samantha rushed to the verandah, barking joyously.

I followed. Two large pink naked soles projected from the verandah's tunnel. I went round outside to the tunnel's exit. Rosebush turned his head, watching me cooperatively. "Just a bit too tight." he remarked. "My younger son does it better!"

And, once through, he would unlock the verandah door and let his father in, and lock it up again after he'd done his robberies.

Samantha licked Rosebush's captive face blissfully. I peered into the tunnel. Rosebush was wearing his shorts again, and I saw no thigh wound. His midnight-raider knife wound was just a tear-jerker. Lying thick now beside Rosebush were many jewels, my Rolex, my gold ring, and lots of cash. That loot that cleared us out had also snared Rosebush. He'd simply not been able to leave it. To catch a monkey, Africans put delights in a cut-open coconut, its diameter the width of a monkey's paw. He gets the lure in his paw, won't let go, so is trapped.

I rang the police. They came fast, young Afrikaners, neat and attentive. They pulled Rosebush out, pockets still bulging. His fingerprints swamped our dressing-tables and our smashed open strong-box. I phoned Soozi, who rushed back. We drank tea in the kitchen, Rosebush's cup in his cuffed hands. He still smiled royally, Samantha swooning at his feet. The police left for a minute, to get forms from their car.

"Would the Nkozikazi kindly lend me 80 Rands?" asked Rosebush, unabashed. "Just a day's wages, to feed my sons."

The police had taken his bulging purse and given him a receipt. He'd get Soozi's 80 Rands out to his son secretly. Of course she gave them to him. In court. the magistrate gave him six months hard. Rosebush begged another 80 Rands from Soozi, which she slipped to his son. A week later I saw a silhouette in the street. Rosebush? Samantha was ecstatic. I was unworried—we'd installed a stronger safe. Samantha insisted, and still hauled me to the liquor cabinet. I checked. Instead of our usual local knockabout Commando brandy, Rosebush had taken the unopened bottle of Remy Martin. The villain even had good taste!

I rang the Rondebosch Police. "You've lost Prisoner Rosebush," I told them.

"We knew," said one of the two who had come, "the prison reported it to us last night. We rang you, but you were out. Rosebush was doing labour on a farm, under guard. He just walked off. A slim oukie, that one!"

A slim oukie was a smart character in Afrikaans. Rosebush was all of that.

"Any joy to our looking for him in Khayelitsha?" I asked him.

"Can't hurt," said the cop, "but he'll be on a bus to the Transkei by now. His visit to you was just his swan-song. He'll not be back till Mandela guarantees him a Mercedes car, mansion and a good executive job."

So Soozi and I repeated our visit to Rosebush's shack in Khayelitsha, and found it totally empty. We went home sad.

"So while Nelson Mandela targets building a million new homes for Blacks," observed Soozi, "and completely reconstructs black education and the job market, Rosebush helps by cutting up the country's cake and re-distributing it more evenly. And the best of British luck to him!"

Perhaps we'd see him back one day, flitting in and out of existence like an ectoplasm, sparking Samantha off into another tartlike search. What had startled me was his nicking our best brandy. He'd made us laugh or cry! He'd had the last laugh all right. His ghostly chuckle still echoed in my ears. His whole saga really inspired. It showed a new and happy non-racial South Africa, a new life, to be smiled about, even half ironically!