Some Measure of Happiness

Some Measure of Happiness

Critique by Jendi Reiter

Critique by Jendi Reiter

Lee Wicks' Some Measure of Happiness is an intimate novel about a year in the life of a group of friends in Cooper Hill, Vermont, as they cope with bereavement, midlife crises, troubled children, and the challenges of being newly single in a clique of couples. In the prologue, set in 2001, prep-school teacher Jack Walker loses his wife and their twin children in a freak accident, and finds himself adrift without her restless, demanding energy. The remainder of the story, spanning 2004, shows how he slowly rejoins the world of the living by helping his neighbors through their own struggles with parenting, aging, and adultery.

Jack would be the first to admit that he is not the hero of anyone's story, an amiable trust-fund baby who snoops in his neighbors' unlocked houses for some clues to reorganizing his shapeless life. Luckily this novel is an ensemble piece, skillfully intertwining the destinies of a half-dozen livelier folks: among them, a runaway teen with a drinking problem, a bitter postmistress, a couple of achingly PC lesbian moms, and a brash but good-hearted divorcée from the city who sets her cap for Jack. You can tell when a writer has lived with animals because their nonhuman characters are neither anthropomorphized nor sentimentalized. Like the horses in Jane Smiley's Horse Heaven or the cats in Patricia Highsmith's stories, the dogs in Some Measure of Happiness have real doggy personalities and unique roles in their owners' families.

The fictionalized Cooper Hill is a white, upper-middle-class, complacently liberal village, culturally similar to Winning Writers' home base of Northampton, Massachusetts, which made us appreciate Wicks' affectionate satire of her characters' political pieties and conspicuous consumption of wholesome products. President George W. Bush's war in Iraq troubles these people from afar—and causes some awkward moments with the one Republican in the women's book club—but on the whole, they're more concerned with making their children eat vegan hot dogs or figuring out which Doctors Without Borders volunteer program has the best beaches.

The flimsiness of these characters' inner resources was the book's main drawback for us. The only ones who try to live by some intentional system of values are the postmistress, with her vinegary and hypocritical brand of Christianity, and the young lesbian couple, forever wringing their hands about trivialities like the feminist implications of their kindergartner's Halloween costume. The rest muddle through the big battles of love and death with nothing more in their arsenal than a bottle of wine and a New Yorker subscription. It would have been a welcome contrast to include at least one character with a deeper-rooted philosophy of life that was not foolish or execrable, like Conrad the accidental Stoic in Tom Wolfe's social satire A Man in Full.

We were also bothered by the fact that the book's one working-class character, postmistress Maud Crowe, was the small-minded villain. Even her last name is a stereotype of the stigmatized, lonely older woman (old crow, crone). Her big misdeed was an excellent plot device, a midpoint hinge to turn everyone else's lives in a new direction, but it might have been more effective to make her secret a surprise for the reader until the characters discovered it too.

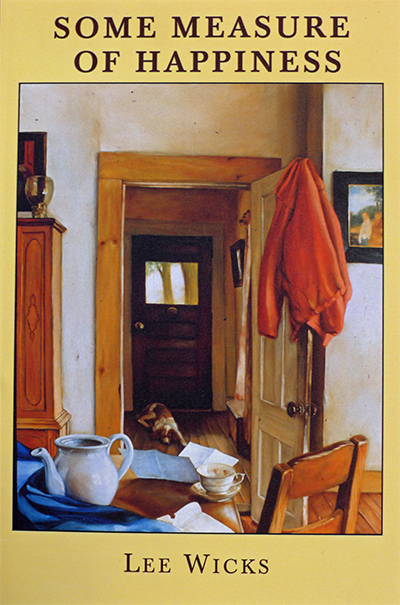

Design-wise, the book from Singing Dog Press had a beautiful cover in pastel yellow, with an original painting by James Whitbeck of a rustic interior scene that captured the book's mood of intimate drama. The large number of typos was distracting. Some Measure of Happiness is a smooth read that will appeal to fans of Jacquelyn Mitchard and Alice Hoffman, as well as dog lovers and New Englanders with a sense of humor about themselves.

Excerpt from Some Measure of Happiness by Lee Wicks on Scribd