The Faller

The Faller

Michael Demaray's literary novella The Faller is a stark but redemptive coming-of-age story set in a rural community in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Logging and mining keep the town's men precariously employed, and violence and alcohol are their go-to methods for grieving. When he loses his parents within the space of a year, 12-year-old Leif must discover how to be wounded without being damaged.

This book's physical and cultural sense of place made it stand out. Some of our fiction writers neglect specificity of setting because they want to delve right into the characters' relationships and interior reactions. To me, this can come across like a stage play on an empty set. Remember that emotions exist in bodies, and bodies move through places occupied by other people, weather, and material conditions that either meet their needs or don't.

In real life, not all reactions manifest as dialogue or even interior monologue. They come across more effectively sometimes in the way the character engages with his physical surroundings, which means you have to show what options for self-expression his particular environment allows or forecloses.

The wrenching first scenes of The Faller exemplify this perfectly. Leif is helping his father, Ernest, with logging in a remote patch of woods. As tough or hoping-to-be-tough guys do, they're bonding over dangerous physical work and sharing grotesque stories, but the intimacy is as fragile as Ernest's life will prove to be. As will eventually be fleshed out in later chapters, there are hints at the cause of Ernest's depression: Leif's mother died of cancer a few months ago, and her brother fired Ernest from his mining operation for drunken brawling. Skinny and sensitive, Leif struggles to live up to his rugged father's model of manhood, let alone to coax him out of his dissociation.

In seconds, everything changes. Ernest cuts his throat in a peculiar chainsaw accident. To honor his father and also cover up the possibility that it was suicide, his son works heroically to load his huge body onto their barely functioning truck and drive back to town. The wealth of physical detail here reminded me of Jack London's survival story "To Build a Fire" or Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea. (Is Ernest's name a tribute to him?) There's no need to explain Leif's pain, or belabor the book's theme that he's carrying a burden too heavy for him, because all of this has become dreadfully literal and concrete.

How do men express grief? How do they express love? Without ceasing to respect Ernest, Leif learns from the other men in his community that his father's ways are not the only or the healthiest ways. That turn towards life, out of isolation and repetition of the past, gives The Faller its beauty and hopefulness in the end.

Design-wise, the interior layout could have been more elegant. It was readable, in a normal book font, but the block-capital chapter titles and the skinny margins made the text look pasted directly from an unpublished manuscript. I found it strange that only the even-numbered pages had numbers on them. Fortunately, there's now a new edition that eliminates these problems, with an attractive large font and elegant chapter headings.

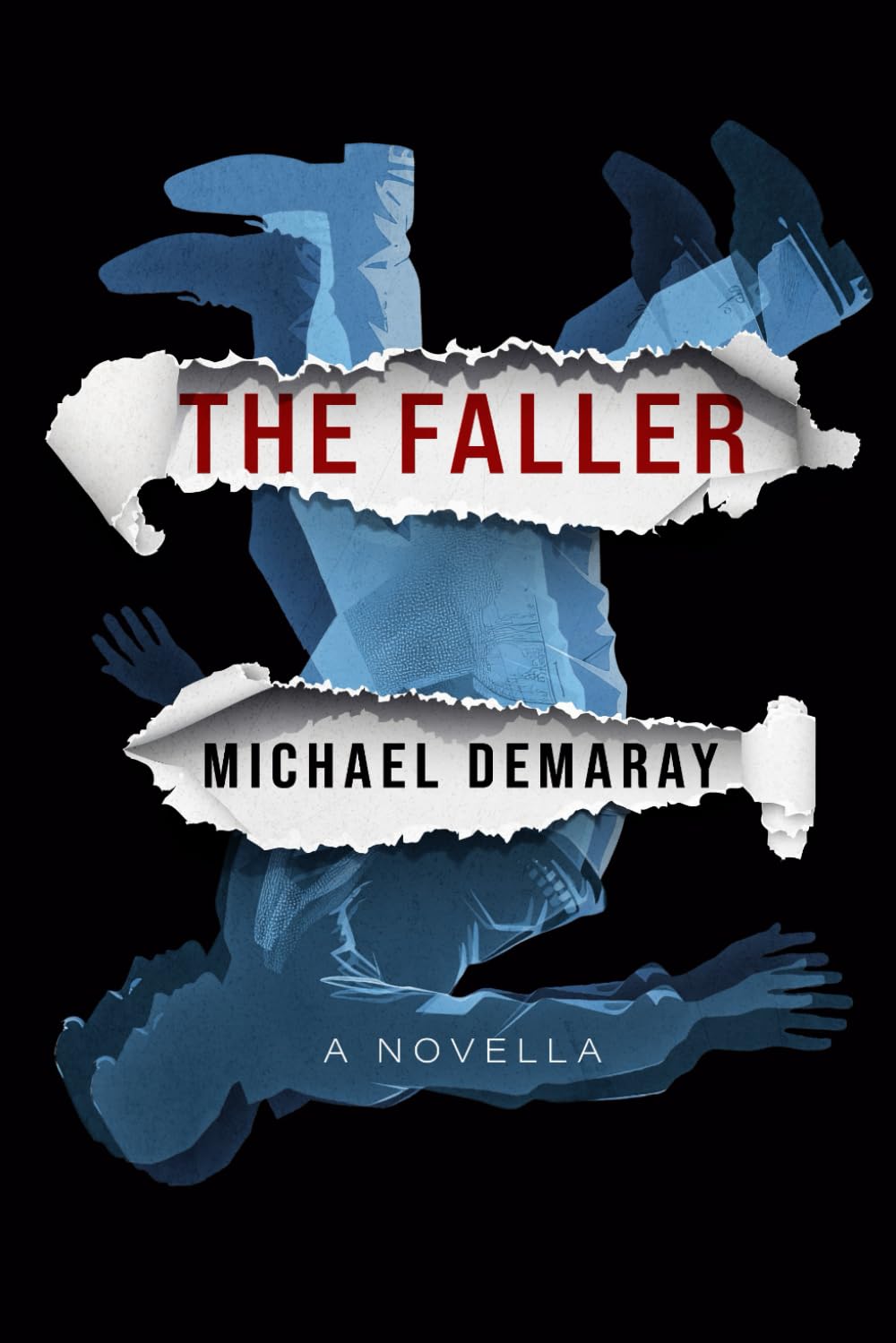

The front cover had an excellent design that conveyed both literary and noir elements. Against a dark blue background with a silhouette of a falling man in work clothes, the title and author name were set inside holes that appeared to be torn in the cover. The version we judged had a tagline at the bottom, "The heaviest burdens we carry are the ones we can't put down". Professionally published books generally don't have these explainers on the front cover. I was glad to see that the new edition eliminated this text, allowing the resonant image to speak for itself.

The Faller is a profound, perfectly paced novella that would be appropriate for a high school English class, as well as a book whose wisdom can be appreciated by adults.

Read an excerpt from The Faller (PDF)

Buy this book on Amazon.