The Long Hot Walk

The Long Hot Walk

Critique by Jendi Reiter

The Long Hot Walk is Deborah McCarroll's compassionate memoir of growing up in New Mexico with her schizophrenic mother. The writing style, particularly in the childhood years, is lyrical and rich with physical details.

Between hospitalizations and her compulsion to wander, Mary McCarroll's mental illness meant that the pair could not put down roots in one place for long. Young Deb had to pull together a ragtag family out of the shifting population of the Catholic Indian Center, a boarding house for Navaho women, where they stayed for four years. Her siblings sometimes provided a refuge but they had their own problems: her brother was fighting in Vietnam and her sisters were overburdened by marriage and child-rearing. As an adult, Deb moved East for a career as a visual artist, but struggled to make personal connections that would replace the intense bond of caretaking her mother.

The book's strengths are McCarroll's poetic style, attention to the nuances of character and setting, and empathy for a difficult parent. The elder McCarroll comes across as someone who tried her best to be a loving mother, but could not help forcing adult responsibilities on her children because of her illness.

In our opinion as contest judges, the memoir's main weakness was the vagueness of the author herself as a character. We felt kept at arms' length from her life goals, personality, and adult relationships. When she was a child, only able to observe events without influencing them, her detachment made more sense. She coped patiently with her mother's constant disruption of her life because she had no choice. As an adult, it would have been natural for her to express some anger and sadness about her deprivation, and to reflect on how it affected her friendships and love life. Although her upbringing was not abusive, it must have been traumatic.

Early on, I picked up hints that McCarroll would grow up to be a lesbian. It was something about the tomboyish way she described herself plus her deep feelings for female friends. However, this plot thread was not clearly developed in the second half of the memoir. Her adoration, apparently unreciprocated, of her co-worker Daniella was frustrating to me as a reader because I could never tell whether they were girlfriends or it was a secret crush. At the end of the book, we suddenly jump ahead to McCarroll living with her partner, Kate. Everyone has the right to tell their coming-out story in their own way, but the patchy and disorganized way that this information was revealed added to our disappointment that Deb's untold story was buried beneath her mother's.

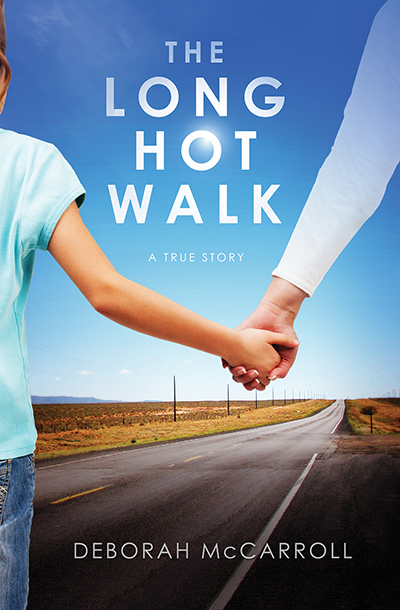

The book design by Studio Pacific ranks as one of the most attractive and professional that we received. McCarroll's training as an artist really paid off here. On the cover, the mother and daughter holding hands on a sun-baked desert road express the core themes of love and exile. The typeface is modern and streamlined, saving the image from sentimentality, with a mid-1960s feel that matches the story's time period. The jacket copy gives just enough information to convey the premise with a taste of the book's lyricism and emotion. Self-published books often have skinny page margins for cost reasons; this one looked like a normal publisher's edition. With some more work on literary structure, McCarroll could take her career to the next level.