Arizabesu

Arizabesu

I am five. My mother has picked me up from school after her lunch shift at the restaurant. She smells like cooking oil, sliced fish, and soy sauce. I am ashamed of her smell, her apron. I am ashamed of how she nods and bows to greet my teachers, and hurries me into the car without staying a while to have a quick chat with the other mothers.

I sit in the middle of the backseat as she drives me home, as we pass by the recently cleared fields of corn and newly constructed houses. I can see the in-ground pools in their backyards through the window.

I ask her to say my name, again and again. I ask her to say it, and each time she says it, I laugh. Each time she says it, I laugh, until she realizes I am mocking her. I can see the corners of her mouth tighten and turn down through the rearview mirror. I didn't mean to hurt her. Or maybe I did.

Arizabesu... Arizabesu... is how she pronounces it.

I am named Elizabeth after my father's mother, my father's mother's mother, my father's mother's mother's mother, and so on. It is a family name, a queen's name. It is Anglo. It is Western. It is white. Like my father.

When I was a child, my mother pronounced my name Arizabesu because the English sounds were unfamiliar, uncomfortable to her. The textures were off. Because she had to concentrate just a breath of a second longer.

As a child, I made fun of the way she said it. My friends made fun of the way she said it. My friends' parents made fun of the way she said it. We thought it was her fault.

* * *

My mother's name is Kyoko, which means "respectful" or "apricot" or "echo" or "from heaven" in Japanese depending on how it's written. My mother was born in Okinawa in 1948, three years after the end of WWII, three years after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, three years after the horrific Battle of Okinawa that destroyed one quarter of the island's population and ninety percent of its buildings and infrastructure.

The Okinawans were not soldiers. They were fishermen and farmers, cooks and carpenters, shopkeepers and seamstresses who were conscripted by the occupying forces of Japan to defend themselves against the attacking forces of the United States. They had no stake in the battle. Except for what they lost. Those who survived lived in caves, tombs, or shacks scavenged from debris and scraps.

My mother grew up poor, hungry poor. She subsisted almost entirely on sweet potatoes her family planted and food rations supplied by the U.S. military. She lived with her father, mother, two brothers and three sisters in a tiny hovel that my grandfather built, that my grandmother scrubbed, mopped, painted, fixed up, and rebuilt for many years, long after her husband died and her children moved out. But while they all still lived there, they ate, bathed, played cards, and slept on mats together in the same room.

My mother grew up hearing the sounds of jets, helicopters, ships, and gunfire coming from the surrounding bases, the voices of foreigners in the streets and stores.

She quit school before she finished the eighth grade, has been a waitress since she was fourteen years old. She always gave some of her paycheck to her mother or her younger sisters, even long after she left Okinawa. Sometimes she still gives some of it to her spoiled daughter.

According to a Japanese legend, if you make a thousand paper cranes you are granted three wishes. My mother made a thousand paper cranes once. Her three wishes were to become rich, marry an American, and have a child—a daughter, fingers-crossed—who could eat as much as she pleased and sleep on a bed in her very own room.

* * *

My father's name is Arthur, which means "bear" or "guardian" or "king" in Celtic. My father was born in Brooklyn, also in 1948, the son of a wealthy Italian immigrant and an English-Irish-Scotch woman who could trace her lineage back to the settlers of Jamestown.

My grandfather salvaged a small amount of his inheritance despite the Great Depression. He enlisted in the U.S. Army during WWII and quickly moved up the ranks as a translator. He could speak Italian, French, Spanish, as well as German and English, fluently. Then he founded one of the first telephone answering services in New York City. My grandmother was his receptionist. She had a sharp mind full of fresh ideas, a by-product of her BA in Economics from Hunter College. She was second in charge. But deferentially, soft-spokenly, of course. She was twenty-two years old, fifteen years younger than my grandfather, when they married. They bought a corner condo on the Upper West Side where they raised three boys. An all-American family. An American dream.

My father and his two younger brothers went to Loyola, a prestigious Jesuit school located on 88th Street and Park Avenue, not too far from where they lived. My father was taught Latin. He was taught St. Thomas Aquinas. He read every play by William Shakespeare, every book by Dickens, Conrad, Orwell, Steinbeck, and Hemingway by the time he graduated from Fordham University, another Jesuit institution. After he declined an acceptance to Georgetown Law, much to my grandfather's dismay, then volunteered to join the Army and serve a tour of duty in Vietnam, much to my grandmother's dismay, he read The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and State and Revolution by Vladimir Lenin because he "sought to understand the mind of the enemy." Yes, his exact words.

Back then, my father believed in heroes, in men, in strong men who protected the weak. He believed in sacrifice and honor. He believed that righteousness was inherent, that rightness could be certain.

* * *

Elizabeth means "God's oath" in Hebrew. I was born in Elk Grove, IL, a suburb of Chicago, in 1981, the year Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as the 40th U.S. President, the year Raiders of the Lost Ark premiered, the year MTV began broadcasting, fourteen years after the Supreme Court declared interracial marriage legal, and seven years after my parents were married on the island of Okinawa.

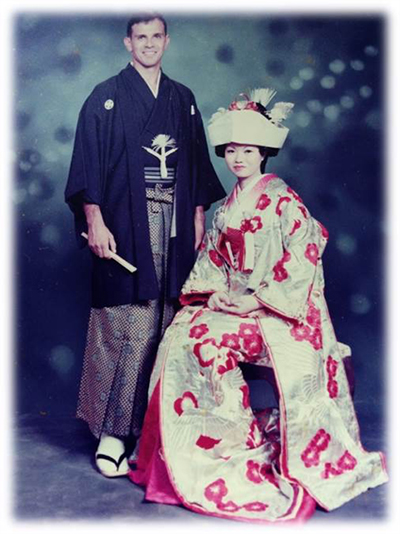

It was a small ceremony. Only my grandmother, my oba, attended. My grandfather was dead. My uncles were too angry and my aunts were too sad, scared, maybe jealous, that their sister was marrying an American, a foreigner, a soldier, that their sister was leaving. My oba, who cleaned barracks, and also prepared bento boxes in her kitchen, then sold them door-to-door while collecting bottles and cans to supplement her income, somehow scrounged enough money to rent two traditional wedding kimonos and hire a photographer to document the event.

My mother has seen her family four times in the forty-two years since she left.

At the time I was born, my father was completing his MBA in Operations Management and my mother was taking ESL classes, both at Northwestern University. My mother hated those classes, she later confided.

"They too hard for me. I want to stop going, but your father not let me. He make me study. He study with me. He help me."

Good for him, I thought to myself. Not yet comprehending the unfairness, the very lopsided power dynamic. Not yet aware of the ease with which she conceived and uttered the word let, the ease with which I heard and processed it. We accepted the word without resistance, with a nod of approval even.

Because my father was the parent who knew what to say when I asked about thunder and lightning, or jumping off a diving board. He knew what to say when I asked about the girls who teased me or the boys I had crushes on. He knew what to say to teachers, gymnastics coaches, my friends, my friends' parents. He knew what to say.

And his pronunciation was perfect.

My father could speak only a few phrases in Japanese. I could speak only a few words. The words for "please" (kudasai) and "thank you" (arigato), the words for the numbers one through ten (ichi, ni, san, shi, go, roku, shichi, hachi, ku, ju), as well as the words for private parts, chin-chin for "vagina" and oshiri for "buttocks," used as euphemisms when my mother needed to confirm that they were properly washed.

Sometimes I believe that the cruelest injustice done to my mother, surpassing the war that ravaged her homeland, surpassing the poverty, surpassing the beatings from her oldest brother, the negligence of her gambling, drank-himself-to-death father and my dear but distracted oba, is the fact that she can't communicate with her daughter in her native language.

I don't know why I didn't learn. I don't know why my father didn't learn and command me to learn like he commanded my mother to learn English. Perhaps ethnocentrism is to blame. Perhaps bilingualism just wasn't very popular in the 1980s.

* * *

My father couldn't afford to live in the nice parts of Manhattan, much less provide for me the private education he had received without the financial aid of his parents, which they gladly would have awarded him. But he was raised on the tenets of rugged individualism and social Darwinism. He was a man, a strong man, a righteous man. So after he completed his second MBA in International Marketing from the American Graduate School of International Management (founded by Barry Goldwater, a libertarian icon), he searched for places for his family to reside that boasted the finest public school districts. He chose Fairport, a suburb of Rochester, NY, the second best after Pittsford, the neighboring district, but he couldn't afford to live there either. At least, he hoped, not yet.

Fairport had a population of roughly 6,000 people, ninety-nine percent white and one percent everything else. The one percent stayed as far away from each other as possible. We didn't want to be associated. Or too visible.

I wonder how different our lives might have been if we had lived in Manhattan, even the not so nice parts, even Brooklyn or Queens or the Bronx. If we had lived in Seattle or San Francisco.

At school, some of my classmates stretched their eyelids with their fingertips and sang the song "We Are Siamese If You Please" from the Disney movie Lady and the Tramp. Sometimes they called me "Data," the "booty-trap" setter from the Donner/Spielberg movie, The Goonies. Sometimes they called me "Chink" or "Gook" as well as a more original yet terribly unclever pejorative, "Gorilla Woman," because of my flattish face, pug nose, and thick eyebrows. They tore pictures of gorillas, chimpanzees, and monkeys from magazines, which they shoved into my desk and locker. This was before the obligatory people of color were presented to the dominant, mainstream culture through Gap and T-Mobile ads. I guess I must have looked unfamiliar, uncomfortable. I must have looked strange.

In fifth grade, a black kid moved to our town from Houston. Everyone thought we would make the cutest couple. On a Saturday, on the playground in the fields behind our school, they demanded that we kiss. I closed my eyes. I lunged forward when I was supposed to stand still. I bashed his teeth with my teeth and busted his lip with my braces.

They laughed at us. He dumped me the next day.

But I don't know if anything can account for how cruel I was to my mother. I ignored her as much as I could, disregarded her as much as I could.

One time I cut up a bunch of her clothes, dresses and kimonos stashed in boxes, because I needed patches for sewing my ripped jeans. These were the same jeans I ripped on purpose because those were the kind of jeans they wore on MTV.

One time I stole three large jars of coins she saved from years of waitress tips and took my friends to a carnival. These were the same friends who stole a diamond necklace from my mother because I showed them where she kept her jewelry. These were the same friends who stole cash from my mother because I showed them where she kept her secret wallet in the first drawer of the China cabinet.

That was how insignificant she was to them. And to me.

I practiced the sarcasm I learned at school on her because I knew that between me and her there was no contest. I knew she couldn't retort or taunt me, not like the other kids. I knew I could outwit and outsmart her even at seven, eight, and nine years old. Especially at ten, eleven, and twelve years old. Sometimes she would get so frustrated at not knowing the words that she hit me. She slapped me across the face, or smacked me on the head repeatedly, or pulled my hair so hard that part of my scalp formed into a bump and throbbed and ached. My father would have to yank her off of me. I never hit her back though, not because she was my mother and I respected her, but the exact opposite. She was weaker. She was a strange woman who looked strange and spoke strange and cooked strange food no one else ate.

And she got drunk. Mostly on her days off. She never drank when she was alone with me. She always waited until my father came home. But when she started, she couldn't stop.

She drank sake and wine. And when the sake and wine ran out she switched to bourbon, which was my father's booze of choice. She called her mother and three sisters in Okinawa. She talked to them on the phone for hours. Then she hung up and burst into tears.

On more than one occasion, I remember my father had to block her from the front door. She would charge and crash into his stout pillar of a body, trying to escape. He would wrestle and restrain her, pin her to the floor, until she punched, kicked, and wriggled free, and then she started charging again. She wanted to go back to Okinawa, she screamed, but she was shit-faced and barefoot and wearing only a nightgown.

Eventually he would have to drag her to the bedroom by her armpits, her legs kicking and flailing, still screaming, and toss her onto the bed. She would be tired but belligerent, crawling to the edge of the bed, trying to escape again. My father would wait at edge, ready to block her, ready to grab her and toss her, gently of course, back down to the bed. He would stand guard, with one foot propped on the edge and one elbow propped on his knee, assuring me with a smile that she would feel better in the morning.

I know he meant to protect her but when I remember these occasions, I think to myself God, how humiliating. I wish I had crawled into bed with her, told her not to worry, told her that I was her daughter, I was home. But I was a little girl then, and more than a little scared and selfish, and I didn't want to be near her.

When I asked my father why I didn't have a Japanese name, that is, a name my mother could pronounce, which I didn't dare say, he answered that he wanted to name me 'Elizabeth' after his mother, after his mother's mother, and mother's mother's mother, and so on. Elizabeth was a family name, a queen's name. My mother agreed.

But could she honestly have objected?

My middle name, however, is Miki, which means "beautiful princess" in Japanese. That was how my parents intended to raise me, as their princess. That was the promise my father represented when he met my mother at the Blue Diamond Bar, where she worked, just outside the army base, where he was stationed. Perhaps she captivated him with her smooth, dark hair, down to the middle of her waist, her petite frame and slender figure. Perhaps to someone who had just spent four years in combat she was just too beautiful, pure, delicate to resist. He had to save her. Perhaps he wooed her with his prep school charm, his generous tips. Perhaps to someone who had grown up sharing a hovel with her father, mother, two brothers, and three sisters, who subsisted on sweet potatoes and food rations, he must have seemed like royalty.

In eighth grade, I decided that 'Elizabeth' was a common, ordinary name. I decided that I no longer wanted to be common and ordinary. Or rather, it was decided for me. I insisted that my friends call me by my middle name. But the new name didn't catch. My friends knew me as 'Elizabeth,' as 'Liz,' as quiet and unassuming and eager to impress. At that age, friends don't let you change so easily.

It is ironic that I insisted on being called a Japanese name but I also insisted on dyeing my hair blond and wearing fake, dark-rimmed glasses that hid the shape of my eyes and lack of bridge on my nose. I remember begging my parents to buy me fake, blue-tinted contacts. They refused on the grounds of expense and frivolity. They didn't mention the term "internalized racism." That term didn't exist in our vocabulary, especially not in Fairport, NY, especially not back then.

The first time my mother saw my dyed hair, she covered her face with her hand and cried. I thought maybe she cried because I was becoming more independent, more rebellious, and how she probably hated that. Years later, after perusing old pictures of myself, I thought maybe she cried because my hair looked so hideous. The color wasn't really blond but sort of an aggressive, gaudy yellow. Now I think maybe she cried because dyeing my hair was yet another sign of rejection.

I bleached my hair so many times it turned brittle. I chopped my hair short and still kept bleaching it. Then I started listening to punk rock and dyed my hair cherry red, violet purple, and midnight blue instead. I listened to angry punk rock and wrote the lyrics of angry songs on the surface of my desk in pen. One afternoon, my teacher sent me to the principal's office and the principal, disturbed by the angry content of the lyrics, sent me to the school psychologist. I went to visit the school psychologist for four sessions. I don't remember exactly what we talked about but I remember she fed me hot cocoa and candy. I remember she called my father to offer her diagnosis. She concluded that I was ashamed of my mother, ashamed of being half Okinawan. My father and I both laughed. "What a hack!" I never went to visit the school psychologist again.

In tenth grade, the cute boy I had a crush on graciously informed me that I would be much more attractive with my natural hair color. I promptly dyed my hair black. But there is no such thing as black hair. Only very very dark, dark brown hair. Only a brown so dark and so deep that it contains many other colors. Sometimes in the sunlight or firelight or lamplight, it reflects tints of yellow, red, purple, even blue, naturally. It took me months to grow my hair out, to return to my natural hair color. But it was too late. The cute boy I had a crush on ended up hooking up with a blonde anyway.

By the time I turned eighteen, I decided I could use my exoticness to my advantage. I got a tattoo of my middle name between my shoulder blades: the kanji inside of a red sun with a white crane flying toward it. The red sun is a symbol of good fortune and the white crane is a symbol of grace. The premise of my tattoo was a bit ridiculous because only gangsters and criminals get tattoos in Japan. Plus I thumbed through an English-Japanese dictionary, consulting my white, American father because my Japanese-speaking, Okinawan mother couldn't possibly know the kanji for my middle name. She never went to high school. I figured she was illiterate.

Sometimes lovers would refer to me as "Miki." They would take it as their pet name. They would take it as intimate. Usually, they forgot to ask permission. Although I enjoyed hearing the sound of it, something felt wrong, fake about it. Maybe because I was never a miki. Maybe because I mocked my mother for not being able to pronounce my first name.

* * *

When I hear my mother say my name now, I just hear it. Her pronunciation does not sound wrong or right. Arizabesu and Elizabeth. They're both mine.

I wish I could locate a precise point of transformation, the pivotal moment when my mother and I finally reconciled. But that's not how we tend to apologize and forgive. The healing is gradual, cumulative. It happens as we begin to recognize our mothers not as mothers but as women who endured husbands and daughters. It happens as we begin to accept and appreciate our very own exquisite uniqueness as well as everyone in our lives we hold responsible. It happens right now as I write.

And besides, this isn't an essay about healing.

I am thirty-five. I am visiting home for the weekend. It is summer in Fairport, NY and the kids are splashing in pools and the parents are mowing their lawns.

I drive my mother thirty minutes to the city of Rochester. We have to go to the Asian market to get fixings for dash broth, kombu (seaweed) and bonito (fish flakes). She plans to prepare a dish of cold soba noodles and tofu for dinner tonight, a delicious warm weather treat.

I listen to music on my phone that is plugged into the car stereo. She asks me how this technology works. I explain that these songs are downloaded, a concept she doesn't quite understand, but that she can listen to pretty much any song she wants by searching YouTube, another concept she doesn't quite understand.

"Here. I'll show you. What's your favorite song?" She tells me the name of her favorite artist and track. I do my best to type the romaji letters. "Can you repeat that?... Say it more slowly."

It's a song I've heard many times. She used to sing it around the house while cleaning or cooking, blaring it through boomboxes from cassette tapes her sisters sent in brightly colored, carefully wrapped packages. I remember the basic melody and try to sing along but fumble over the verses.

"I guess I don't know the words," I say, laughing.

"That's okay. I'll teach you."

She bobs her head and pats her knee. She sings loudly and clearly so I can hear her.