As Waters Gone By

As Waters Gone By

Natural disasters undermine not only our physical infrastructure but our structures of meaning. Why were some spared when their loved ones died? Does it help or harm the victims to analyze how they may have put themselves in danger? Dr. Asome Bide's memoir As Waters Gone By recounts how one Cameroonian community approached these questions after a devastating landslide.

Bide, his wife, and her sister are members of a Cameroonian immigrant community in Silver Springs, Maryland, where he works as a pharmacist at Johns Hopkins. His father-in-law, Pa Lang, happened to be visiting them in America in June 2001 when torrential rains in Lang's home village of Limbe caused the mudslide. Hundreds were left homeless and 23 people were killed. Among them were Pa Lang's wife Mama Ewei, three of their children, his nephew, his two nieces, and his grandson.

The post-disaster chaos and finger-pointing paralleled the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Some blamed the villagers for building on unstable ground, but poverty and government corruption had left many without better housing options. Politicians in Cameroon made promises at media appearances, yet found legal loopholes to avoid compensating families for loss of life, as opposed to loss of property. Disaster relief councils lined their own pockets instead.

Bide and his wife had a strong conservative Christian faith that helped them work through the trauma as a test of strength. Pa Lang and his neighbors sought other methods of regaining mastery of their fate. Returning to Limbe for funeral rites, the family encountered rumors that a feud or a curse was to blame for the deaths of Mama Ewei and the children. Neighbors even turned against Pa Lang, believing that he was spared because he must have plotted their deaths for personal gain.

As an educated, Westernized man who nonetheless demonstrates a strong connection to his home culture, Bide is an intriguing narrator of these competing systems of meaning. The tone of his writing is detached and even-handed, empathizing with the villagers' desperate need for a moral explanation, but his loyalty is naturally with his innocent father-in-law. Emigration has given him the critical distance, and perhaps the political freedom, to indict the Cameroonian government's failure to provide for its citizens.

The organization of the book is orderly and clear, with the dates of events given throughout the narrative in order to anchor the reader. Photographs of the family add poignancy and help the reader differentiate the large cast of characters.

I found the style of the writing initially less approachable than what I expect from a memoir, but I chalked some of that up to the differences between American and Anglophone African literary conventions. The tone was rather formal throughout, and the descriptions of emotional states were sometimes reliant on cliché imagery. I will say that transitions between the personal narrative and the sections of factual background were generally smooth. Though the final pages of "where are they now" data about the political players was informative, it felt like a flat and abrupt way to conclude such a dramatic tale.

I realize this is Pa Lang's story first and foremost, but I was curious how Bide himself felt about the villagers' belief system. How did it interact with his Christian faith? Did his greater worldly experience make him critical of their certainties? I didn't get to know him well enough as an individual.

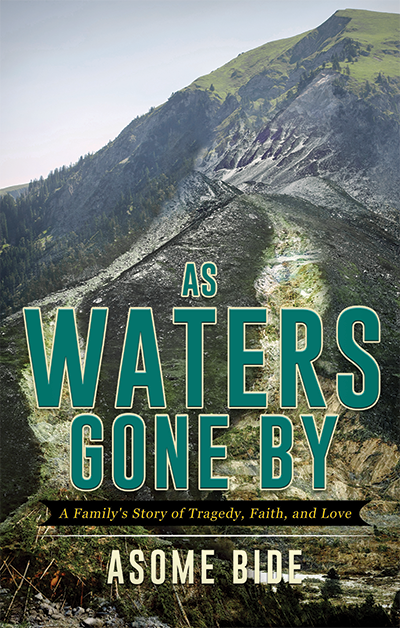

The book was nearly typo-free, with a sturdy paperback binding, a readable typeface and professional layout, and an attractive yet somber cover photo of a steep grassy mountain (presumably in Cameroon). Readers will learn a lot from this unique memoir.

Read an excerpt from As Waters Gone By (PDF)

Buy this book on Amazon