Black on Madison Avenue

Black on Madison Avenue

"From the very beginning, Black people were always in advertising," longtime ad executive Mark S. Robinson opens his lively and informative memoir, Black on Madison Avenue. "The only difference—the whole difference—was that the advertising was not created by us, and it was not created for us." He explains that some of the earliest ads in colonial America were for purchasing enslaved people or seeking their recapture. When modern consumer marketing emerged in the 1880s, Black people were featured as mascots, like Aunt Jemima or Uncle Ben, to give white consumers that high-class feeling of having Negro servants in a bottle.

With this witty introduction to his reminiscences of 40-plus years in the industry, Robinson signals that this is no dry business memoir or fluffy celebrity tell-all. I was immediately hooked.

Advertising was in Robinson's blood from the beginning. The son of a fashion model and a commercial photographer, he was an Amherst College student when he was recruited for the Minority Advertising Internship Program in 1977. He found his vocation at once. But he wanted to be in account management, the client-facing side of the business, not the media department, dreaming up campaigns behind the scenes. The glass ceiling for Black account representatives was extremely thick, and their numbers were scarce. Robinson describes how he rose in the industry, up to a point, and then had to decide whether to keep fighting for promotions or join a Black-owned agency—a one-way career move, as the white-owned Madison Avenue firms would never hire someone from a minority company. Nonetheless, he made the leap, and thrived on his own terms.

I enjoyed the anecdotes about the many famous brands and ad campaigns that he worked on, which I never realized were the brainchildren of Black executives. Among his iconic promotions were the Fancy Feast cat food commercial with Eva Gabor (a staple of my 1980s TV-watching childhood) and the first Black doll in the American Girl line, which Robinson's team got onto Oprah's "Favorite Things" list. He also partnered with Spike Lee on a short-lived agency affiliated with DDB Chicago, and was hired by Showtime Pay-Per-View to publicize the infamous boxing match where Mike Tyson ended up biting Evander Holyfield's ear. These are just a few of the dishy stories that lighten up Robinson's well-documented exposé of racism in the ad industry.

Robinson is generous in praising the unsung heroes and heroines of Madison Avenue—his fellow Black executives and the allies who gave them their well-deserved opportunities. Whereas many memoirs are narrowly focused on the author's travails, he's really written a story of his community. Personal narrative, industry statistics, and historical context are smoothly woven together. At a tight 225 pages, it covered a lot of ground without getting lost in details.

On the negative side, the book had some erratic punctuation and capitalization throughout. The style was not particularly literary. I would have liked to know a little more about Robinson's personality and relationships outside work, though perhaps his long hours and ambitious overseas projects didn't leave much time for anything outside the job. How did his wife and children handle his many absences? The downside of the book's tight thematic focus is that it feels impersonal sometimes.

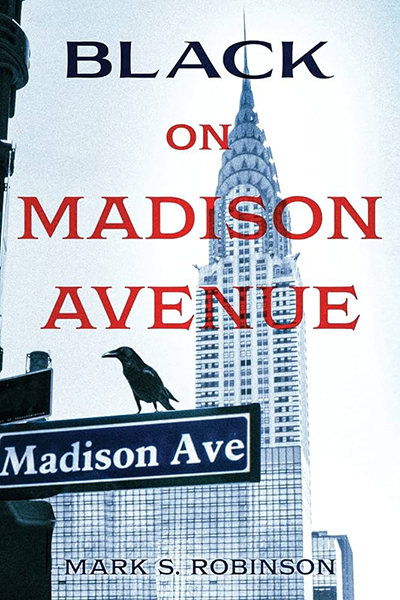

The cover design was simple and dramatic, if not especially imaginative, showing a crow perched on a "Madison Avenue" street sign in front of the Chrysler Building. I felt the duplication of "Madison Avenue" in the title and the sign should have been avoided. With respect to the back cover, designers should take note that italicized small white type on a black background is not the most readable choice.

Black on Madison Avenue is a consistently entertaining and educational read, as well as an important historical document. I was pleased to discover this unique entry in our contest.