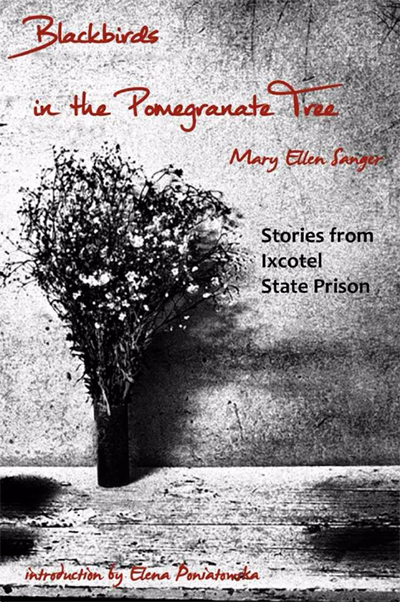

Blackbirds in the Pomegranate Tree

Blackbirds in the Pomegranate Tree

Critique by Ellen LaFleche

Critique by Ellen LaFleche

Many teachers of English caution against using too many adjectives when writing. But that rule has been temporarily suspended for the purpose of this critique; it's impossible to discuss Mary Ellen Sanger's memoir Blackbirds in the Pomegranate Tree without using as many superlative adjectives as possible. This book is lush, lyrical, magnificent. Magical and mesmerizing. Poetic. Eye-opening. It's an important book that pleasures the reader with visual and auditory descriptions of nature and landscape while exploring the harsh grittiness of prison life.

Sanger was a young American woman who left a high-stress career to take a public relations job in the Mexican tourist industry. The early part of the memoir combines mundane details of her personal life with vivid images of Mexico's indigenous flowers, plants and people. I wish I could quote the entire book here. Since that is impossible, here is a sample literary delight.

I walked over mountain paths in the tag-along light of the pre-dawn moon, listening to the sunrise as chirring insects hid away, and the first birds awakened. I shifted under my skin. Oaxaca glistened with rare ambers, jades and rubies. Indigenous colors. A scarlet bird on a golden cactus bloom... A Chinantec woman poised in a crimson blouse embroidered with rainbow geometries that held the history of her family.

The middle part of the book pivots into scenes of horror. Sanger was suddenly and unexpectedly sent to prison as the result of a land dispute involving the house in which she was living.

This part of the book uses an interesting literary technique in which her first-person account of life in a Mexican prison is interwoven with chapters describing the lives and struggles of individual women. Sanger is both an observer and participant in events. The chapters about the women are the heart of the book. These women have experienced poverty, rape, loss of children, abandonment. They have beautiful faces, they have faces ground down by years in prison. They are proud, they are shamed. They are patient, they are rageful.

Sanger spent hours a day in the prison yard sitting under a tree and writing her thoughts and observations. But she was also subjected to many of the same abuses and deprivations as the other women prisoners. I appreciate that she was able to acknowledge the ways in which her financial and racial privilege set her apart in many ways from the women she lived with. Her situation received a lot of political attention in the United States and she was freed after a month behind bars.

The ending of Blackbirds in the Pomegranate Tree describes Sanger's post-prison life in America and was not as powerful as the rest of the book. The text has almost no proofing errors and was aesthetically appealing with readable print. I hope this book reaches a wide readership for its poetic imagery and its contributions to women's studies and Mexican cross-cultural understanding.

I wrote this critique in the final days of January 2017, when Donald Trump's desire to build "a wall" along the Mexican border has put Mexico in the news. Most Americans, myself included, need to know more about Mexico, its history, economics, and people. As a native New Englander with family ties to Québec, I know a lot about Canada; I've visited it many times and speak both languages. But I know little about Mexico. This lack of knowledge about our other national neighbor cannot stand, especially now. This book has made me realize that many Americans need to know more about Mexico—lots more. I urge everyone to read this book and learn about this beautiful and complicated country.

Excerpt from Blackbirds in the Pomegranate Tree by Mary Ellen Sanger on Scribd