How They Met

How They Met

Author's Note: The Battle of Okinawa began April 1st, 1945 and ended June 22nd, 1945. The entire island was devastated. Crumbled and charred black from bombing and shelling. 183,000 U.S. troops invaded the island, wielding tanks, grenades, and guns. 122,000 Okinawans, nearly one third of the population, almost all civilians, were killed. Almost all the rest were left homeless.

Mother and older sister disappeared in flame then smoke, nowhere to be found. Grandmother lost her sight and grandfather lost his limbs, we can't remember how. Grandmother and grandfather tell us to leave them behind. We beg them to let us stay. We don't want to be alone.

"We will fetch water for you. We will scratch your backs, pick off maggots and squeeze the pus out of your wounds for you. Please let us stay here and die with you."

We beg and weep for two whole days but they still refuse. "You're too young to die just yet. You can't give up. You must go."

So we obey. We dig a hole. We leave them in the hole with the rest of the food, not much, just a jar of miso paste and some dried squid. We cover the hole with branches. We cover the branches with dirt. We place stones in the shape of a circle on top of the dirt. We shout at them through the dirt and branches, saying goodbye one last time, promising to return when the war ends and bring their bones to our ancestral tomb. They do not answer us.

We hope they die calm, sleeping beside each other. We hope they breathe their last breath in silence, after the bombing and shooting finally stop.

When the war ends, we return to the hole but the hole is gone. The Americans have built a road over it. We search for scattered bones along the side of the road but the road keeps widening. The Americans build roads over tombs and graves, marked or unmarked. The Americans build roads through smoldering fields, through embers and ashes of homes. The Americans build roads in between stations and camps, clusters of tents expanding and spreading so fast, we can barely recognize our island from one day to the next.

The Americans can build in a day what takes us months to build.

The Americans can destroy in a day what we will never forget.

We will never forgive ourselves for leaving grandmother and grandfather behind.

We will never forgive the Americans.

Inside the camps, we stand in long lines so soldiers can feed us. They feed us food stuffed into tin cans that doesn't resemble any food we have ever eaten before. They feed us popcorn and candy. Inside the camp, doctors and nurses tend to our sickness and wounds better than we ever could. If one of us asks for water, they just bring us water. We used to tell ourselves that drinking water would make us sicker, because we didn't have enough water to spare. Inside the camp, we live in huts and tents. We sleep on the ground and when it rains, we sleep in mud. Inside the camp, we wear discarded uniforms. Our children run around in shirts five sizes too big and sometimes we sew clothes from torn parachutes.

Outside the camp, we are afraid to walk alone.

A crowd of us has gathered on the road beside a field. We are watching as one of them, a young man, twenty years old, drags one of us, a young girl, sixteen years old, from a tent across the camp, and then across the road into the field. Her mother, one of us, clings to his leg, begging, wailing, making awful animal noises that force us to stop walking, force us to listen and watch. He kicks the mother off his leg and drags the girl farther into the field. He rips off her clothes and pulls down his pants. We watch because we want to bear witness. We watch because bearing witness is the only power left within us. We watch because the horror doesn't frighten or madden us anymore.

We watch until he is done with us, until our mother crawls to us, then wraps a blanket around our stunned and trembling body. We watch, and those of us who can bear it, look at him directly in the eyes. We want to make sure he sees us. We want to make sure he knows we're watching. We don't scold or attack him. We don't seek revenge. We just keep walking. Because that is the only power left within us. Because we are done with this war.

Outside the camp, we shove poles into the ground and hang large bells from the poles. When we see one of them approaching, we ring the bells to warn each other, then run away and hide.

Between 1945 and 1949, one thousand of us are raped.

Those of us who give ourselves willingly to the Americans, those of us who get paid to give ourselves, are called pan-pan. We are called whores. Some of us are widows. Some of us are young girls who still live with our mothers. It doesn't matter what they call us, or what we call each other. At least something is being done. At least we're getting paid. After all, our island is covered in ash and dust, filled with stench and rot. There isn't anything for them—or us—to do except drink until we are numb and fuck. Some of them would rather pay us than rape us and for that some of us are grateful.

They come stumbling out of the bases, through the barbed wire fences, through our villages. They shout and slur our names. We invite them into our homes. Sometimes our mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, and children sleep—or pretend to sleep—on the other side of the walls. Some neighbors complain that we are dishonoring our families, defiling the children. Some neighbors try to banish prostitution but when we ask how else to feed our families, our children, the neighbors have no answer so we come up with a better solution. We move to the outskirts of the villages. Our homes become brothels and our brothels become districts.

By 1967, ten thousand of us become prostitutes.

We are done with this war. But they're not. They have a war to fight in Korea, and then a war to fight in Vietnam. "As long as communism is a threat," Vice President Richard Nixon announces during his visit in 1953, "[the United States] will hold Okinawa." They must use our land to build a fortress to protect the "Free World". A world in which we are not included. They must use our land to launch ships that carry tanks and guns, to launch planes that drop bombs. We shudder with each sound as ship after ship departs, as plane after plane takes off, remembering the massive damage those ships and planes have caused. They must use our land to store missiles and poisonous gases. We feel guilty, complicit, even though we have no choice.

Forests and fields that have just begun to heal are bulldozed and replaced with concrete. Farms that once grew pineapple and sugarcane, staple crops that once sustained our meager economy, are bulldozed and replaced with concrete. Family-owned plots that have been passed down for generations are confiscated, sometimes at gunpoint, and residents are evicted. One hundred thousand of us assemble at their headquarters in Naha and they agree to pay us for the land they already stole.

But it is not enough. Not nearly enough.

So we become labor. We are hired to build their bases. We are hired to build barracks, armories, loading docks, landing strips, fences, gates, more roads. We are hired to serve food in their cafeterias and clean their houses. The prettiest of us, who have curves and speak the best English, get to work at the post office and fancy restaurants like McDonald's. Cities form around these bases, with bright neon signs in English, advertising to them, welcoming them. With bars and clubs where soldiers can yell and laugh and fight and flirt with waitresses and spend money like it's their last day on Earth, because, well, who knows, their last day could be very soon. They're fighting a war and they pay us to help them forget.

But we remember. We will always remember.

Some of us fall in love with them. Is that so strange? Because they're tall and strong and polite. Taller and stronger and more polite than many of our men, since most of our men are gone. Because they carry heavy bags and boxes for us. They open doors for us, and let us enter or exit in front of them. They pull out chairs for us. They offer us their seats and stand for us. Because they drive us home in their cars and trucks, so we don't have to walk home alone at night. Because they're rich. They make more in a day than we make in a month. They smell like soap when we can only rinse our faces and armpits with water from buckets or soak in a public bathhouse once a week. They leave us big tips and buy us gifts. Perfume, make up, silk stockings, chocolate, chewing gum, bottles of liquor and cartons of cigarettes that they bring from their bases and we sell to each other for cheaper than we can get anywhere else on the island. Because they let us watch movies on their televisions and wash clothes in their washing machines, so we don't have to wash clothes in the river. Because sometimes they buy us our own televisions and washing machines. Sometimes they pay our rent.

Because some of them are gentle and genuine, warm and kind, foolish and impetuous, and very young. Just like us.

Some of them fall in love with us. Is that so bad? Because we're tiny and shy and vulnerable. Tinier, shyer, and more vulnerable than many of their women, who are far far away. We blush and we giggle. We lower our heads and avert our eyes. Because that's how women are supposed to act, that's how we're told women are supposed to act. We don't speak much English, so they can't understand us. They don't know us. So they look at our faces and imagine who we are, see who they want to see. They look at our faces and see themselves as they want to be seen. We can't understand them. We don't know them, either. So we imagine that they are brave and good, will protect us and take care of us, never hurt us. Because we're undeniably grateful for everything they do for us. We're not angry, not like those of us who are older. Not like the men, who hate them because they're taller and stronger and richer. Because we're not used to men approaching us and treating us like beautiful, delicate flowers. We're not used to men lying to us in such a way that we have to believe them, lying to us in such a way that they have to believe themselves.

"Don't confuse sympathy for love," one of their mothers writes back to one of them.

The first "international marriage" in Okinawa was recorded on August 1st, 1947, in the Uruma Shimpo, a weekly newspaper written by Okinawans and supervised by American military officers to inform the public about policies and directives, as well as local news. The marriage was between Frank Anderson, a twenty-three-year-old soldier from Ohio, and Higa Hatsuko, a nineteen-year-old seamstress from Ginowan. They received their certificate from a civilian governor. Their marriage was annulled by a commanding officer one month later.

According to the War Bride Act of 1945, spouses and children of Armed Forces personnel were allowed to enter and reside in the United States—"if admissible." However, according to the Immigration Act of 1924, otherwise known as the Asian Exclusion Act, marriage between Americans and Asians was considered illegal. Upon hearing this shameful news, Frank Anderson turned to his ex-wife and said, "Then we'll hold hands, and by the time we get to America, I believe Congress will have changed the law."

And Congress did, eventually, in 1952, with the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act.

Before 1952, there were a few exceptions, temporary reprieves of maximum Asian immigrant quotas. In 1948, during a month-long lifting of the ban, eight hundred twenty-five marriages between U.S. servicemen and Japanese citizens, including Okinawans, were recorded. The newspaper, Uruma Shimpo, noted that an "extremely high proportion" of these marriages occurred in Okinawa compared to the rest of Japan. So much so that in 1948, the U.S. Military issued a special executive order prohibiting marriages between servicemen and Okinawans, referring to an overall best practice of "nonfraternization" in occupied areas.

From 1952 to 1975, sixty-six thousand Japanese women emigrated to the United States as wives of U.S. servicemen. More than half of the total Japanese immigrant population. It is difficult to determine precisely how many of those Japanese women were actually from Okinawa, or if there is a separate number. After 1952 and until 1972, Okinawa was a territory of the United States. Okinawans were not recognized as Japanese, yet certainly not as U.S. citizens. However, since seventy percent of U.S. military bases in Japan are located in Okinawa, it seems safe to assume, as the Uruma Shimpo once noted, that an "extremely high proportion" of these marriages occurred in Okinawa compared to the rest of Japan. Plus, there is significant anecdotal evidence. Just ask any Okinawan.

For many years, it is forbidden. For many more years, it is ridiculed. We are called pan-pan. We are called traitors. We are called Yankee-lovers and gold-diggers. We meet with them in secret. And when it comes time to tell our families, some of us are told we are no longer daughters. No longer sisters.

Our families warn us not to leave with them. "If you go to America, you will be lonely. If you go to America, your children will be tormented. They will call you Jap. They won't accept you." Some of us refuse to listen. Some of us listen but refuse to believe what our families tell us. Some of us do believe, but decide to leave with them anyway.

Some of us leave by ships bound for San Francisco, filled with a thousand or more passengers. Soldiers, sailors, marines, and a few dozen of us, their new wives. We sit together on the dock and stare at the ocean. Talking, dreaming, admiring our new husbands, promising to visit each other all the time. At night, they show movies and host parties. We drink and dance with them, except those of us who are already getting sick in the morning. The voyage takes fifteen days and each day reminds us how far away we are from home.

Some of us arrive by planes, in New York, Boston, Philadelphia. We look around the airport and don't see anyone else like us and immediately we realize we've made a big mistake. "Is it too late to go back?" we look up at our husbands and ask. Our husbands look down at us and nod, their faces confused and sad. Some of us have to sit in a car while our husbands drive for two days, four days, six days, across this vast and magnificent country. We have never seen mountains so high and terrifying, deserts so dry and engulfing. We have never seen roads so wide and smooth. We had no idea. Not even an inkling. We feel even smaller now, humbled. "How much longer?" we look up at our husbands and ask. Our husbands look down at us and smile, proudly. "Just a couple more days."

Some of us find out that our husbands already have wives. They put us in a trailer on the edge of town overlooking a field of corn. They visit us once a week to drop off groceries. They watch TV and drink six cans of beer while we sit beside them. Sometimes they let us sit on their laps. After they leave, we are afraid to go outside. We are afraid to answer the phone. We wish we were dead and some of us swallow pills or slit our wrists and crawl into bathtubs.

One of their wives comes over and beats us. One of their wives comes over and tells us it's not our fault, and asks if we need help getting back home. But we can't go back home and bring more shame to our families, more shame to ourselves. So some of us stay and raise children by ourselves.

Some of their mothers hate us. Some of their mothers are the only reasons we can bear this strange and frightening place. Some of our neighbors ignore us. Some of our neighbors notice our isolation and take us out for walks or shopping at the mall. Some of our husbands turn cruel, call us "stupid" and "ugly" in front of our own children. Some of our husbands remain sweet and bring home puppies or kittens or promise to give us more children to cheer us up.

When we see each other by chance, in passing, we follow each other until we get close enough, until we muster the nerve to ask, "Anata-no Nihon-jin desu ka?"

"Hai, hai! Nihon-jin desu. Watashi-wa Okinawa shusshin desu."

"Watashi-mo!"

Then we bow and cry and hug and become friends forever.

My mother and father met on the island of Okinawa, where my mother was born and raised, where my father was stationed after serving two tours of duty in Vietnam. They met just outside the Kadena Army Base, at the Blue Diamond Bar, where my mother worked as a waitress, getting paid one dollar for every drink she got a serviceman to buy for her. Perhaps she captivated him with her silky dark hair, flowing down to her waist like water. Perhaps to someone who had just spent four years in combat, she was just too beautiful, vulnerable to resist. He had to save her. He had to make something good come from a lost cause. Perhaps my father wooed my mother with his prep school accent, his charm, his chivalry and generous tips. Perhaps to someone who had grown up eating sweet potatoes her family planted and rations the military provided, who grew up living in a tin-roofed shack with her mother, father, two brothers and three sisters, he must have seemed like a way out.

They met at the Blue Diamond Bar, then dated for several months, then my father was stationed in Korea for a year. They wrote each other several letters. He wrote his in English. She wrote hers in Japanese. They asked friends to translate. He proposed to her in a letter. She accepted his proposal in a letter. They needed friends to translate. My father returned to Okinawa and they lived together for a year before they married on the island, on December 12th, 1974. Marriage to locals was discouraged but as commanding officer my father granted his own approval.

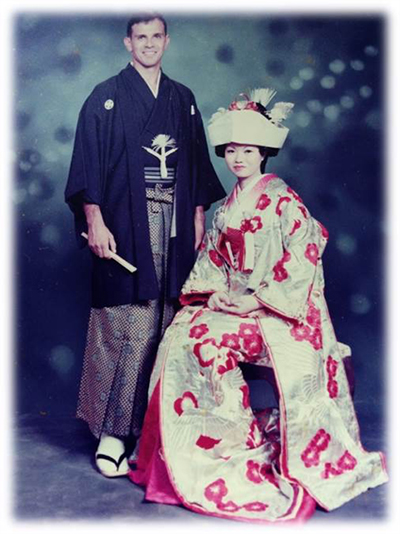

It was a small ceremony. Only Obaasan, my grandmother, attended. My grandfather was too sick, my uncles were too angry, my aunts were too sad, scared, maybe jealous, that their sister was marrying an American, that their sister was leaving. Oba managed to scrounge enough money to rent two traditional wedding kimonos and hire a photographer to document the event.

My mother has seen her mother twice in the forty-two years since she left.

My parents arrived in San Francisco by boat. My father bought a brand new car, a Datsun B210 hatchback, and they drove for eight days, across mountains and deserts, through lonesome plains and eerie swamps, through enormous cities bigger than entire islands. My father wanted to show off his country. My mother had no idea how long it would take. They drove to New York City, the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where my father was born and raised, where my parents lived together with my grandparents for the first year of their marriage. My grandfather was tight-lipped and stiff-shouldered. My grandmother was smiling and let my mother dress her in kimonos she had brought for her. My grandfather told my father that there were plenty of pretty daughters from nice Italian families who would have loved to marry a former soldier and captain, a retired Airborne Ranger and Green Beret. My grandmother told my father that my mother had lovely manners and the most beautiful hair she had ever seen.

My parents slept in my father's childhood bedroom. At night, my father, my grandfather and my two uncles stayed up late, drinking bourbon, talking, laughing, playing cards in the dining room. At night, my mother was alone. One night she snuck out, took the elevator to the first floor, wandered the dark streets until she found a bar. After several drinks, after several hours of sitting alone—a nice girl like her in a place like this—the bartender called the house. My grandmother answered the phone. My uncles laughed. My grandfather wanted to know what kind of girl sneaks off by herself late at night. My father hung his head low while my grandmother yelled and stomped her feet and ordered my father to go out and find my mother, bring her back and promise to never stay up late again. My father always listened to his mother.

My mother told me that if it weren't for my grandmother, standing up for her, saving her, again and again, she wouldn't have lasted.

When I ask my mother why she decided to marry my father, she says because he was very handsome and polite and left big tips. She says he always ate whatever Oba cooked for him, he always knelt at the tatami table even after his feet fell asleep. She says my father bought her a car and taught her how to drive. She says she wanted to get off that sad, poor island. Get away from her sad, poor family.

When I ask my mother if she was in love with my father, she says "Well...now I am."

"Well what about back then?"

"Probably not," she says and laughs. "I guess I don't really know."

I guess that's fair. How many of us really know?

When I ask my father why he decided to marry my mother, he says because she was very beautiful and clean and loved music. He says—without reluctance or reflection—that while serving his tours of duty in Vietnam and Korea, he formed an image in his mind of the woman he wanted to marry, and my mother fit that image perfectly. Perhaps he wanted to redeem himself for all the lives he ended, all the lives he couldn't save, but he has never ever told me that. He says when he went away to Korea, he couldn't stop thinking about her. He missed her more than he thought he would, more than he had ever missed anyone in his life. That's how he knew.

When I ask my father if he was in love with my mother, he says "Of course."

When I ask my mother if she was scared to move to America, she says, "No, I was very excited. I had never seen so many big buildings or cars before. I always wanted to go to Disney World. I didn't know how hard it was going to be. I was too young."

I ask her if she ever wishes she had stayed in Okinawa.

"I used to."

"What about now?"

"No. Not now. I'm too old."

REFERENCES

Crissey, Etsuko Takushi, and Steve Rabson. Okinawa's GI Brides: Their Lives in America. University of Hawaii Press, 2017.

Higa, Tomiko. The Girl with the White Flag: a Spellbinding Account of Love and Courage in Wartime Okinawa. Kodansha USA, 1980.

Keyso, Ruth Ann. Women of Okinawa: Nine Voices from a Garrison Island. Cornell University Press, 2000.

Martin, Jo Nobuko. A Princess Lily of the Ryukyus. Shin Nippon Kyoiku Tosho, 1984.

Zeiger, Susan. Entangling Alliances: Foreign War Brides and American Soldiers in the Twentieth Century. New York University Press, 2010.