Manny

Manny

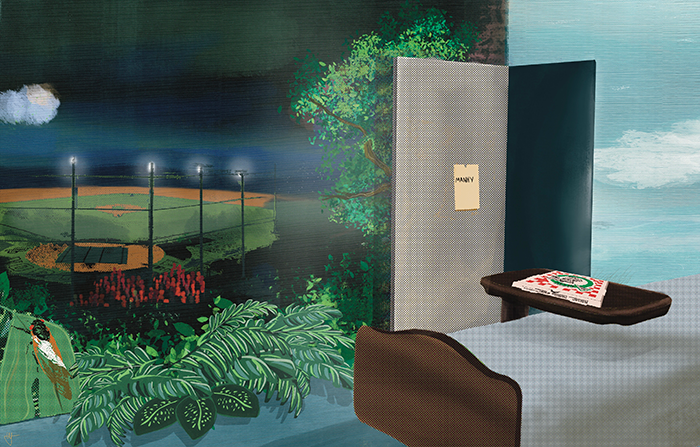

Illustration by Clara Longo de Freitas

January 2015

At just past three in the morning, the seventh floor was quiet, its cramped patient rooms dark save for the cool blue lights of pumps and monitors. Children dozed in unfamiliar hospital beds, their limbs wrapped in delicate tangles of wires and tubing, while their parents contorted their bodies to fit recliners under industrial blankets that smelled like bleach.

As the city sky outside the windows turned from black to navy, nurses moved inaudibly in and out of rooms, their hands pressed to sweaty foreheads, ears filled with heart and lung sounds, nimble fingers finding spaghetti veins in the darkness.

Everywhere in the hospital, night crept in slow, lonely seconds toward dawn. Yet even as the glow of TV screens extinguished around the floor like candles, even as the elevators paused their relentless motion and the normally bustling lobby turned languid and thick with silence, Manny's room vibrated with sound and light.

It had been that way for weeks now, a ceaseless pocket of noise and motion, discordant screens and speakers and hospital equipment. Room 246 could never be dark or still or silent, because inside Manny was dying of cancer, and any trace of those things filled his broken 18-year-old body with fear.

"Can you sit with him?"

I looked up from my computer to see Katie at the nurse's station. Her face was flushed, and her arms were full of IV medication bags and tubing sets. There were two nursing stations on the unit, one on each end of the long, horseshoe-shaped hallway, and Katie and I were the only two nurses with patients on the east side of the floor that night.

"His mom needed to go downstairs," Katie continued. "And I'm late on pretty much everything else I have to do for my other kids right now."

I glanced at my computer, at my own long list of overdue medications and tasks. It had been a long, busy shift, and I had already been in Manny's room with Katie a half dozen times that night to witness boluses of Ativan or Morphine, all failed attempts to stem his anxiety and pain.

"His mom won't be gone long."

I looked up at her and felt a pang of guilt. I had been so relieved that night when I arrived, to not be assigned Manny. But that simply meant it was another nurse's burden.

"Of course."

Her face softened into relief.

"Oh my God, thank you."

"It's no problem. Does he need anything right now?"

I asked as I came around the counter.

"We just did a clinician bolus on the PCA," she said, glancing down at her papers. "He had his last Ativan and fentanyl thirty minutes ago. So, he should be good for at least a half hour on everything." She glanced at her watch. "Just call if anything comes up."

A few moments later I stood at the door to 246. It was the largest private room on the floor, and the only room with its own sitting area. It was also the only room with a mural, a hand-painted forest scene against the back wall, with wide-eyed deer and rabbits against a calm green backdrop.

Unofficially, it was the hospice room, chosen because it was spacious enough for multiple family members and also secluded, tucked in a corner away from the playroom and its chirps of laughter, away from the outdoor deck with its colorful slides and swings.

Near the door there was a small sitting area, with a couch that had been unfolded into a bed for Manny's mother. Like most nights recently, it looked unused, the sheets and blankets still neatly tucked in. She spent most of her time in the navy recliner, or closer, right on the bed next to her son, her strong, middle-aged fingers encircling his thin, mottled ones, her steady voice in his ear, assuring him it would all be okay, even as they both swayed from the violent crashes of his failing body.

The overhead TV was on at full volume and set, per Manny's request, to an outdoor nature station, hour after hour of shows about boats or trucks or people in the wilderness. I glanced at the TV to see the image of a lone boat rocked by massive waves as the crew hauled metal crab traps aboard a rain-soaked deck.

Manny sat on the edge of the bed underneath the hard-white glare of a half-dozen overhead lights. There was a green metal oxygen tank on the floor beside him, which emitted a continuous rushing sound as it flooded oxygen into Manny's nose. One of the nursing computers had been wheeled into the room and placed a few feet away, set to an online station for relaxation music, its gentle electronic melodies in sharp contrast to the grunts and shouts of the people on the television. A large IV pump was attached to a stand a few feet away from him, and long, clear tubing ran in tangled arcs into the port on his chest.

Manny looked up as I approached. Every centimeter of his pale, anxious face was magnified under the bright lights. His cheekbones, once soft accents in an otherwise plump, boyish face, were now sharp edges that hung over the deep pockets of his cheeks. Without eyebrows or eyelashes, his eyes looked bigger than they really were, dark brown ovals surrounded by blossoms of blue and green.

"Hey Manny," I said as I approached. He watched me as I pulled a small plastic chair close to the bed. His eyes were focused but exhaustion and a haze of opiates blurred the edges. It had been days, weeks even, since he had slept in more than short fragments of time.

"Do you mind if I sit here with you for a while?"

He stared at me, swaying slightly, and I could see him struggle to stay alert. But I also knew that any second, the switch would flip, because with Manny it always did. It didn't matter how exhausted he was or how little he had slept. It didn't matter how frequently the palliative team increased his morphine or Ativan or Haldol, how many times the nurses paged the doctors throughout each progressively longer night, pleading for higher and higher dosages.

Manny's cancer was terrifying, the way it tore through his lungs and bones and brain, the speed with which it grew and flourished in his once strong, athletic body. But it was nothing compared to the aggression and velocity of his fear.

I sat down in the chair. Manny stared past me into the room, toward the door, and I watched his chest rise and fall in rapid, labored breaths.

I glanced at the monitor next to the bed, its screen dark. It was one of the many concessions to Manny, and one of the many battles at this point in his care. He asked frequently to have his heart rate and blood pressure checked, wanted to keep the pulse oxygenation sticker on his finger. As a hospice patient with a DNR, there was no need for any of it.

But even as his parents and care team attempted to reduce the invasiveness of the hospital, create a gentler, more peaceful environment, Manny clung to medicine, to the alarms and routines and labs. For him, there was no hospice, no comfort care. To accept those things would be to accept drowning. It didn't matter how far from shore he drifted, how endless or cold the sea. It didn't matter how many times the hospital chaplain stopped by his room or how tightly his mother held him and promised him he could rest.

Anyone who spent any time in that room knew that for Manny, there would be no peaceful surrender, no gentle release. He was 18, and none of us could change the fury or desperation with which he clung to life.

As if sensing my thoughts, Manny turned his head toward the monitor and held out his arm.

"Will you check it?" he asked, his voice thin and hoarse.

"I can," I paused. "But I think Katie is going to do that soon. So maybe we can just wait until then?"

He didn't move his arm, but his eyes grew unfocused. Gently, I placed my hand on his shoulder and guided his arm back to the bed.

"Will you listen to me?" he asked abruptly, his eyes suddenly wide and desperate. He picked up a stethoscope beside him on the bed. "My chest hurts." He swallowed. "I feel like I can't breathe."

I hesitated for a moment, but then finally took the red plastic stethoscope as he held it toward me.

"Okay."

Manny leaned forward as I placed the silver bell of the stethoscope on his chest, just underneath the top of his hospital gown. I took a small breath of my own as his deteriorating heart filled my ears. Manny was a full-grown adult, but his heart beat like a newborn's, with a rapid, irregular cadence.

I moved the bell of the stethoscope, pretended to concentrate to the sound of his struggling lungs, to the deep, rough currents of oxygen, shallow, desperate breaths to match his shallow, desperate heart.

I had only been a nurse on the pediatric floor for a year, and yet, even at 28, I was so sure I understood death. I believed there was some order to it, some promise of grace, particularly for a child. But I had never seen someone die like Manny, watched a beautiful young body resist with so much violent opposition.

I took the stethoscope out of my ears and placed it on the bed.

"Everything sounds okay," I said as I sat back in the chair opposite him. He looked at me, his soft brown eyes the only part of his emaciated face that remained unchanged from when I met him.

"Can I have the mask?" he asked, slurring his words.

I nodded, stood up and took the clear plastic oxygen mask off his IV pole. He sat motionless as I placed the mask on his face, wrapped the green cloth strap around his smooth head.

"How is that?"

He nodded and took a long, shuddering breath. I let my hand rest on his thin back, felt atrophied muscles tensed beneath his gown.

"Do you want to lie down? Try to get some sleep." I asked quietly, even though I knew the answer, the same as it had been for me and his mother and so many other nurses and doctors over the last few weeks.

He shook his head and took another ragged breath as he reached for the small plastic button attached to his morphine pump.

I stood there as he pressed it, as the machine beeped and emitted a mechanical whir to signal the release of more morphine into his bloodstream. It should have been more than enough to make him sleep, to relieve his pain and anxiety. It all should have been enough, the hundreds of tools at our disposal there in that big, reputable academic hospital with its pedigreed physicians and boundless technology.

We should have been able to make him comfortable, to give him that at least. But his teenage body defied all of our efforts, all of our science and knowledge and expertise. We were failing, and every nurse and doctor who walked into his room felt the catastrophe of that failure, the unforgivable fact of his suffering, and our irrelevance in the face of it.

I lifted my hand from his back and took a step toward the chair.

"Are you leaving?" he asked suddenly, his voice muffled by the mask. When I looked back at him, his eyes were not the eyes of who he so recently was, a six-foot-tall, popular, confident high school senior, but the eyes of a small child afraid of the dark.

"No, I'm not leaving."

I sat on the bed and looked back at Manny, his eyes unfocused now and half closed, his bald head bowed. And then I looked past him, out the window on the opposite wall, at a city full of sleeping people in dark, quiet rooms a million miles away.

"I'm not leaving, Manny," I repeated, because there was nothing else I could do except sit beside him, the two of us alone in the brightness.

•

October 2014

I fumbled to cross Manny's room, dark except for the glow of emergency lights and the muted TV screen attached to the wall. It was just past four in the morning, and the room was quiet except for the mechanical hum of Manny's IV pump.

I took soft steps toward the bed, careful to step around the bags and belongings that had piled up like snowdrifts during his admission. Neither of his parents were there. They lived over an hour away, and after the brutality of the last two weeks, no one begrudged them a night at home, a few hours away from gray hospital food and the endless interruptions.

I stepped carefully around the plastic bedside commode beside the bed. Manny hated it, preferred to walk to the bathroom, but the medication required to control the pain in his back made it unsafe for him to cross the short distance at night alone.

When I reached his bed, I stopped and put a hand on the bedside rail. Only a small patch of Manny's smooth, bald head was visible. The rest of his body was nearly obscured by an enormous stuffed bear that was wedged into the hospital bed next to him.

A friend of his had brought it in, one of the few of Manny's high school friends who still visited with any regularity. It had been meant as a joke, something to make him laugh, or ease the awkwardness of the visit.

But somewhere in the space of time since my last shift, after words like palliative and futile began to appear with alarming regularity in Manny's chart, the bear began to spend each night in Manny's bed.

I glanced up at the PCA pain pump on Manny's IV pole. The PCA, like the bear, was a new component of Manny's care, as well as regular Ativan and Benadryl to control his nausea and anxiety. So much had shifted in the weeks since his previous stay in August, back when there were banners and balloons strung over his door to celebrate his last scheduled inpatient chemo, when we all stood at the elevator bay and cheered at his discharge.

He wasn't supposed to come back to us. But a few short weeks later there he was, in a wheelchair from the emergency department, pale and bent over in a new and terrifying pain.

"Hey Manny," I whispered into the quiet as I placed a hand on his back. He didn't move. He had been awake most of the night, alternately in pain or nauseous from the medication required to control his pain. But now he slept deeply, his back rising and falling beneath my hand in slow, easy waves.

"I need to get to your port to do labs, okay?" I said, my voice a little louder. Manny still didn't stir, but carefully, I picked up the enormous bear and lifted it out of the way. It was soft and warm from being pressed up against Manny in the bed.

For a few minutes, I worked in silence, pulling on bright green sterile gloves and opening supplies for his lab draw onto the small table by the bed. Finally, I turned back to Manny to attach the tubing to his port. As my hands brushed his bare skin, his eyelids fluttered open.

"Hey," I said, as I unscrewed the cap on the end of his port. "Just getting your labs okay?"

He blinked and stared at me, his eyes thick with sleep, but he didn't say anything. I attached a syringe and pulled back as dark red blood filled the tube.

"What's for dinner?" he asked abruptly, his speech heavy and his eyes still unfocused.

"It's early Manny," I said as I flushed a tube of saline into his port. "Still night time."

He looked down and watched as I unhooked the empty flush.

"I asked for Subway," he mumbled.

"It won't be dinner for a while."

He lifted his head and it swayed back and forth.

"Why don't we get you something to snack on?" I turned to the tray and picked up the syringe of blood to transfer its contents to the small rainbow of tubes beside it.

Behind me, Manny let out a loud exhale.

"Okay, I'll have a milkshake," he said, the words slurring together.

I turned to look at him. I had never seen Manny this sedated. He rarely received anything stronger than Benadryl or Oxycodone, even at diagnosis or after his resection surgery. But this was the first time I had taken care of him since since a dozen new tumors lit up his scans like tiny, horrible moons.

Everything was different now. There was no scheduled chemo or surgeries. The regimented protocols of his earlier admissions had been replaced by painful, delicate conversations, hushed voices in the hallway, long, unstructured days where the only goal was to simply alleviate the pain. There was vague talk of going to Philadelphia or Boston, experimental trials or new therapies, but no one spoke of it with much conviction.

Manny was the center of it all and yet he was completely removed from it, adrift in a haze of opiates and benzos, flimsy and light.

"What kind of milkshake?" I asked, as he flopped himself back down to the bed.

He made an exaggerated shrug.

"I can do chocolate or vanilla. That's what I saw in the galley when I last looked."

"Maybe strawberry," he said, his jaw slightly slack, his eyes already heavy again.

I looked down at the tubes of his dark blood, still warm to the touch.

"Not sure if we have that one, but I can check."

Manny swallowed and watched me gather up my supplies, his face half buried in his pillow. His cheeks had lost their steroid puffiness, and his strong features were once again prominent, wide, strong nose, high, graceful cheekbones, dark almond-shaped eyes.

I placed the tubes of blood in a clear bag and turned back to Manny.

"How's the pain?"

He shrugged again, his expression a little more focused. At different points during the night, his lucidity fluctuated. Sometimes, he spoke clearly. Other times he talked in vague, confusing tangents.

He reached for the pain button on the bed. It emitted a tiny blue flicker of light as it blinked. He pressed it and turned his head toward the television.

"You ever watch this show?" he asked.

I turned to the muted TV to see a show about people who drove trucks across long stretches of ice.

"I haven't," I said, watching as a tense-faced man navigated an enormous truck across a vast sheet of white earth. "Is it any good?"

Manny shrugged, his eyes reflecting the light of the TV in the dark room. "It's okay."

I picked up the empty syringes and walked across the room to throw them in the sharps container.

"Do you think it's cold there?" Manny asked, his voice soft and mumbled. I looked at the TV.

"Probably freezing. It would have to be, with all of that ice."

I walked back to the bed.

"I like the cold," Manny said, each blink a little slower. "Snow and sledding. There's a hill near my house." He closed his eyes. "It's not that big but if you hit it right, and it it's icy, you go flying." His mouth twitched, the look of a half-remembered dream. "I hope it snows this year."

"Me too," I said quietly.

Manny grunted and reached toward the end of the bed. He fumbled for a moment before his hand closed around the stuffed bear. Without opening his eyes, he pulled it up in the bed until it was beside him, one arm draped over it, his face pressed into the fur.

Manny's breathing slowed, and his mouth opened slightly. And for a long time, for a minute that felt like an hour, I stood there, my eyes fixed on his long, slender hand, the way it clutched the ridiculous oversized bear.

I had known Manny for months, and a hundred images fought with the one in front of me.

Manny in button-down shirt and tie the night of the oncology prom, embarrassed over the attention from the nurses, a half wave over his shoulder as he led his girlfriend down the hall, one hand in hers, one hand on his IV pole.

Or in his room, in a tee shirt and a baseball cap, basketball on the TV, a group of teenage boys crowded in the room with him, open pizza boxes littering the bed, jokes and nudges as I brought him a small plastic cup full of pills.

He used to walk the unit in long, slow circles, pace up and down the halls like a caged animal. For so long, he refused to wear the hospital gowns or eat the hospital food or sleep in the hospital beds. He was polite and charming, but he also found every opportunity to shut his life to us, even as he grew bald and moon-faced and pale.

He had been so sick for so long. But it wasn't until that moment that I had seen him act like he belonged to that place, to those gray rooms and windowless hallways. As I watched him, I felt a sadness settle into my stomach like a weight, a deep ache for the world that existed before I knew Manny, or any of the children like him, the ones who would never go home again.

I reached for the large gray call bell that was draped over the top of the bed. And careful not to wake him, I placed it beside Manny's pillow, so that it would be there when he opened his eyes.

•

March 2014

When I opened the door, Manny sat upright near the window, framed against a thousand tiny embers of distant light.

I took a few steps into the room. Near the door Manny's mother slept on her side, her face turned toward me. Unlike her tall, muscular son, she was a tiny woman, with soft, round features and dark, gray-streaked hair.

She stirred slightly as I stepped around her bed but didn't wake. She had been exhausted when I met her earlier that night, polite but pale and quiet. She had spent the previous night in the emergency department, in a bright, noisy room that smelled like peroxide, watching as more and more people with bright yellow badges walked into her son's room, each more somber than the last, bringing with them words like opacity and mass and sarcoma.

Manny's bed was empty as I approached. All of the lights were off except for the television, which played a sports channel on mute. He sat, as he had that entire night, in one of the hospital recliners at a nearly 90-degree angle. It was the only position that offered him any kind of relief from the pain in his back, pain not caused by a slipped disc or a muscle strain, as his mother initially assumed, but by a five-centimeter tumor wrapped around the base of his spine.

"Hey," I said in a low voice. Manny turned his head toward me, his brown eyes alert, even at that late hour of night. "Time for another set of vitals."

He nodded and shifted slightly in his chair. His face tightened as he moved, and for a moment he closed his eyes and stayed very still.

"I'm guessing that last oxy is wearing off," I said quietly as I slipped the pulse oxygenation monitor onto his right index finger.

He opened his eyes, and rubbed his left hand through his dark, curly hair.

"A little."

"It's still early for the next dose. But I can page the doctors. See if we can increase it maybe, to hold you a little longer." I pressed a button on the monitor next to his bed, and the screen blinked to life with a soft beep.

He stared down at his finger as the oxygen monitor glowed red in the darkness.

"I'm fine," he said.

We both looked at the monitor as it lit up yellow and emitted a low alarm. His heart rate was 108.

"Where's your pain right now?" I asked, glancing toward the other bed, where his mother shifted her weight but didn't open her eyes. "1-10."

He looked up at me.

"You guys like that question."

I nodded as I wrapped a blue blood pressure cuff around his arm.

"We're big fans of numbers around here. Makes the paperwork easier."

He stared at the cuff as it inflated around his arm but didn't say anything.

"Unfortunately," I said into the quiet, "I do need a number. At least a ballpark."

The cuff let out a low noise as it loosened, and we both looked at the screen to see a reading of 139/75.

"Maybe an 8.5," he said finally. "But I can wait until the next dose. It's fine."

I unwrapped the cuff around his arm. He wasn't an adult, but he also wasn't a child. If he were younger, I could ask his mother about increasing the pain medication, bypass him completely. So many things were easier when they were little. I could soften the edges of the unit with games and toys and pizza on the dinner menu, distract them, keep the harder truths blurry and distant. But Manny was too old to protect.

"Okay," I said. I picked up the thermometer and handed him the probe to put under his tongue. While we waited for the read, I glanced out the window. Unlike the other side of the unit, which looked over downtown, all glass and glittering city lights at night, Manny's view looked out away from town. At night, with only a crescent of moon in the sky, the landscape was vast and barren, empty land stretching all the way to the horizon.

The thermometer beeped, and Manny handed the probe back to me. I took the oxygen monitor off his finger, and he eased back into the chair. Even in the dark I could see his mouth tighten, hear the sharp intake of breath.

I glanced at the empty bed beside Manny, the blankets still neatly made and tucked in tight hospital folds and corners.

"What about Tylenol or ibuprofen now, while you wait for the next oxy?" I said with a look toward the clock. "And we have the lidocaine patches. Or heat packs."

He stared at the TV above my head and made a noncommittal shrug.

"Okay then," I said. "We'll try those, see if it helps."

For a long moment, he didn't respond. As I was about to turn to leave he spoke.

"What time is the thing tomorrow?" He paused and swallowed. "I mean, do you know when they'll take me for it."

"I'm not sure," I said. "I can try to find out for you though."

He looked down at his hands. He wore a large gold ring on one of his fingers. It looked like something he would have received from a sports championship. I knew he was a baseball player. Somehow that fact had found its way into Manny's nursing report, a little speck of humanity amidst all of the dire results and grim prognostics.

"How long does it last?" he asked as he moved the ring in slow circles around his finger.

I swallowed. It was the first time that shift that Manny had acknowledged, even indirectly, what was about to happen to him. Until that moment, we had both danced around it, smiled and made small talk about his favorite subjects in school, where he wanted to go to college, pretended he was there for any other reason, a sports injury or bout of food poisoning, something logical and fair.

"I'm not sure about that either," I said. I was only a month out of orientation. There was so much I still didn't know. But I couldn't tell Manny that, couldn't admit that I was new and scared and overwhelmed. Or that every time I left his room, I fought the urge to walk to the supply closet and cry. I hadn't yet learned how to look at a 17-year-old with aggressive, metastatic cancer and pretend it was just part of the job.

"I don't think it should be very long," I added. "I'll try to find out exactly."

Manny nodded.

"That would be great," he said. He looked back down at his ring. "Hannah wanted to know what time she should come in the morning."

I had met Hannah, his girlfriend, earlier that evening. She was pretty, blonde, and far too young to be sitting in a hospital room with her boyfriend the night before a tumor biopsy. She perched nervously on the bed, held Manny's hand for hours and brought him an enormous bag full of fast food that slowly grew cold on the bedside table.

"She can stay in your room, even if you're not here," I said.

Manny nodded.

"I mean, I'll be sleeping for a little while after, right? Like they put me out and everything." For the first time, I heard fear drop into his voice, like a pebble breaking the calm surface of a lake.

"You'll be under anesthesia," I said, careful with each word. "So, you'll be asleep. And it can take a while to fully wake up after. You might be groggy, but they'll keep you in the recovery area until you're a little more alert."

Manny looked out at the window at the ashen sky.

"Okay," he said finally. I waited for him to say more, to ask more questions about the next day. But he was quiet. Whatever moment there had been, whatever lapse that allowed him to speak freely, was gone.

"I'll be back soon," I said finally. "Is there anything else you need right now?"

Manny shook his head. Beside us, his mother let out a long, slow snore.

I hesitated. There was something else to say. Some right action to take. Some way to tell him that it would all be okay, to convince both of us that morning would bring a more logical world. I wanted to assure him it would be over soon, all of the tests and pain and waiting, that he would go home, back to his pretty girlfriend and bedroom full of sports trophies, to high school hallways full of acne-faced teenagers.

If I had been a more experienced nurse, or had known what was to come, maybe I would have stayed with him, a little bit longer, so he wouldn't be so alone in those lingering, empty hours of night.

But I didn't know. Neither of us did.

And so, I left him there, in the hospital recliner, in a dark room while his mother slept, waiting for the dawn and all that it would bring.

•

Out of the hundreds of children I cared for, Manny is the one who comes back most often, usually at night, in late, fading hours, or early in the morning, when the world is pale and blue and quiet. It's been years now since I sat beside him, years since I listened to his brave, frantic heart try so hard to compensate for his failing body. Eight winters have passed since the one that took him, eight years where I've woken up to hushed, snow-coated mornings, watched my breath curl in tendrils toward clear January skies.

But still, Manny remains, defiant in memory the same way he was in life, unwilling to fade.

I wish I had known Manny before he was sick. I was there for the last winter of his life, but without the rest of it, without summer and spring, the years of beauty and warmth, his story feels unfinished. I can't accept Manny's life as I knew it, those broken months of deterioration, the long struggle between a teenager's will to live and cancer's cruel mirror of that will.

It would be unfair, and inaccurate, to tell Manny's story only as I witnessed it, to suggest that his horrible death was some kind of conclusion, to leave him alone once more in memory, in so much pain and fear.

Manny's life ended in that bright, noisy hospital room, with a soft, green forest painted on the wall next to his bed and a window that overlooked the gray March city. But before that, before I met him, there was summer.

Not his last summer, when he was in treatment, bald and puffy and sick.

But a summer that was long and bright and golden, full of fast food and cheap beers snuck from basements, hot, muggy nights in parking lots or empty fields, a constant buzz of talk, where to go next, what to do, the dazzling, infinite possibilities open to a 16-year-old on a June night.

There were days at the river, soft, cool mud on bare feet, the taste of silt and algae. And bright afternoons at the pool, the feel of warm skin and the sharp, tangy taste of chlorine, the way the world looked beneath the surface, blue and undulating and streaked with sun.

There were days and weeks and months, copious, gorgeous time, a certainty that it would always be that way, that there would always be a next summer, that life would stretch endlessly toward a moveable horizon.

And there was baseball.

A night game, bright lights against an orange sky.

The evening air warm and heavy, dripping with the humidity of late summer, dense with the sounds of cicadas and frogs, the soft, drifting smell of honeysuckle.

A red clay baseball diamond, a wide, unkempt field of brown, overgrown grass, a handful of beat-up metal stands filled with parents and teenagers.

Manny at sixteen. Tall and tan. With a mop of dark, curly hair tucked into a uniform baseball cap. He stands at the mound and glances at the stands, at his smiling girlfriend, at his parents, there in the fading sun and heat, the way they've been for all of his games, as long as he can remember.

Manny looks at home plate, sizes the opponent up, his stance and stature, the way he holds the bat.

He knows before he even throws the pitch, hears the swish of metal through the air, the satisfying thud of cowhide against leather, the cheers and applause for the final out and win.

He sees how it will end. His team surrounding him, as they have on so many other summer nights. Admiring looks from his friends, annoyed looks from the other team. A kiss from Hannah when he greets her in the stands, the taste of lip gloss and spearmint.

A hug from his mother, even as he pretends to struggle against it, the smell of cold cream and fabric softener and home.

The night will end as it always has, and summer will drift forward, lazy and unhurried.

Manny knows all of this as he leans back at the mound, one arm behind him, muscles taut and ready. His shoulder rotates. His arm accelerates in a graceful, powerful arc. His entire body tilts forward, and for a moment all he sees is the red, clay dirt.

But he looks up just in time to see it, the brief, beautiful glimpse of the ball as it flies through the air, its trajectory infinite and perfect against the darkening sky.