Peregrination

Peregrination

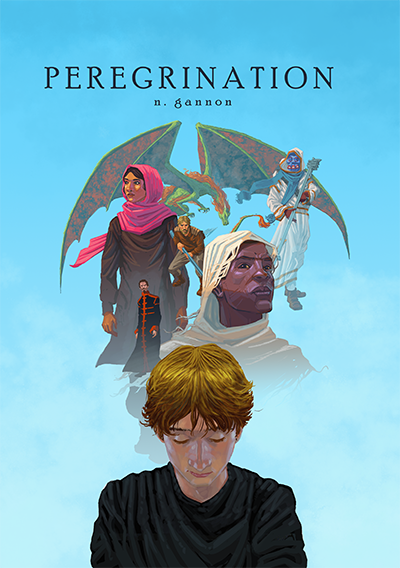

Ned Gannon's visually stunning graphic novel Peregrination weaves together two stories of spiritually sensitive young men who wonder where they fit in the world. One is a wandering monk in a medieval fantasy realm, and the other is the modern-day schoolboy who draws the monk's adventures as a way to process his alienation from peers and teachers. Themes of sacrifice, exile, and violence converge as the scenes alternate between the two storylines.

The monk's tale is illustrated in full color with captions, while the boy's scenes take place in largely wordless black-and-white panels supplemented by his handwritten journal entries. This technique, a classic example of which is the selective use of Technicolor in The Wizard of Oz, clearly conveys the emotional poverty of his real environment compared to the creative richness of his inner world.

Particularly in the color sections, Peregrination contains some of the best art we've ever seen in this contest. The painterly, soft-edged brushstrokes give the monk's world a dreamy quality. I was reminded of the great fantasy illustrators Maxfield Parrish and Michael Hague. The black-and-white scenes are shadowy like a pen-and-ink wash, as though his life at school is one long rainy day.

In light of the book's sophisticated vision and skilled design, the judges were surprised that such a hard-to-read font was chosen for the color captions. The typeface is too small and the skinny lines show up poorly against backgrounds with multiple colors. Fortunately, the journal's handwriting font was both realistic and legible.

Both storylines are saturated with the yearning to be understood, to find a means of expressing love that will be recognized and reciprocated. The monk is cast out of his monastery, the only home he remembers, because they fear his mysterious talent for walking on air. He journeys from bandit-ridden forests to a North African desert where he rescues a captive king from slave traders, enduring hardships everywhere in order to protect victims of injustice. At last he reaches the sky castle where other people with his talent reside, but this community is also too narrow-minded towards those who differ from themselves. His final, unresolved journey is one he must walk alone, like the astronaut at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey passing through surreal color-scapes to a place beyond human concepts.

Meanwhile, as he grows up from about ten years old to high school age, the boy struggles with arbitrary and judgmental discipline from teachers who misinterpret his neurodivergence as stupidity or disobedience. He makes a couple of close friends but sometimes feels baffled by the subtext of their relationships. A few supportive adults keep him on track as he develops into a talented artist. When he learns about Sophie Scholl and the White Rose, an anti-Nazi resistance group in 1940s Germany, he comes to realize that being out of step with the majority is sometimes a good thing.

At the story's climax, a school shooting tests the resilience of the community he has forged. However, I found the ending too ambiguous. The Scholl reference felt like the story was setting the boy up to be a hero and protect his classmates, but it is not clear what action he took, if any. This was a bigger problem for me than the other ambiguity over whether he survived. Nonetheless, it was a beautiful book whose wordless scenes leave room for readers to elaborate with their own emotions. It opens up ways for older children, teens, or adults to process frightening situations through images when words fail.