Reflections

Reflections

Illustrations by Maria Sweeney

for Lois

I woke to spring this morning. Plum trees batted against the open window, and a hard, purple knob landed on my pillow. I stretched toward the sun, the first bright bulb of my calla lily watching from the sill. It was a lazy Sunday, so I pruned back my rosemary and cut aloe clippings. A New World warbler rested on the plum branch, all lemony crown and golden belly. He was eyeing the wayward plum on my bed, so I tossed it onto the grass. I ambled to the fridge, where I was propagating dillweed. I fingered the long, white roots. They reminded me of my grandmother's hair, almost opalescent in the sunlight.

I keep dillweed for protection, like my grandfather showed me, and eucalyptus by the front door to ward off ill intent, like you taught me. I tucked the roots into compost dirt and secreted a wish into the soil. If you were still here, you'd tell me to line the bottom of the pot with rocks for drainage, to use plantain peels as fertilizer, to invoke my ancestors when nestling the small white scrap of paper with my wish scrawled on it. But you can't find plantains in New Mexico, and I'm still working on my relationship with my ancestors. I think you would tell me that's okay, to take my time. I'm writing this for you as much as I am for them. Thank you for listening.

When my grandfather died, I refused to go to his funeral. Once, he hit my grandmother so hard she sustained brain damage. She couldn't even follow a recipe afterward, and her pot roasts came out of the oven crumbling, spilling their innards on the counter. My mother was watching from the closet when the crowbar came down on her skull. Twenty years later, I read the words I cleaned up the blood so Dave, Chris, and Little Greg wouldn't see in a yellowing journal with a broken lock.

He died peacefully, surrounded by his children and the woman he married after my grandmother had to be put in a home. Sometimes I wonder if he ever hit his new wife, but by the time he married her, he was already old and feeble. Harmless, my mother would tell me when I declined trip after trip to their crumbling Victorian on the outskirts of Pittsburgh.

My mom wanted me to go to the funeral in her stead, since I was already up east for college, and she couldn't afford to go. After my dad left, we racked up bills for Grandma's care. Besides, she told me, he loved you. He would want you there. At the time, I thought I was establishing healthy boundaries by telling her no, prioritizing my own wellbeing over an abusive man's wishes. Now I know I was doing it to spite him.

Instead of weaving my way to Pennsylvania on the Amtrak, I made a CD of my grandfather singing traditional Irish songs like "Mo Ghile Mear" and, somewhat incongruously, a rendition of "Fly Me to the Moon" set to bagpipes. I sent it to my step-grandmother, who overnighted my Pap Pap's journals to me in return. For my granddaughter my Pap Pap had scrawled on the first page. I spent weeks poring over hybrid metaphysical-medical entries such as

Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica, Neantóg, devil's claw, burn hazel)

gout, rheumatism, protects prostate

increases milk production in lactating women and animals

banish unwanted spirits, break curses

use in protection bags

Note: diuretic, avoid if low blood pressure

When I called my mom to ask about the notebooks, she said, "They're from your great-grandfather. Pap Pap transcribed his journals and added to them when they got to America."

"The one from the mantel?" A brooding man with sunken cheeks always watched me as a child from his gilded frame.

"Aidan. He was always gardening, always doing something with plants. I remember picking weeds in the yard with him as a girl. When I went to throw them away, he stopped me. He boiled them and made dandelion tea with the roots. I learned later it's good for the liver."

"Good thing Pap Pap had his little folk remedy or his liver might have started failing him a few decades earlier," I said. The words felt wrong in my mouth, and their bitter aftertaste lingered long after I hung up.

Our last summer together, you and I pierced each other's ears. We only had one lemon half between us, so we passed it back and forth, pressed it behind our earlobes and let the blood catch between the flesh and the rind. Red ran down your neck, and I licked it, registered the metallic tang only after my tongue had traversed from cartilage to clavicle. When it was my turn, I may have cried. You held my hand as the needle lodged in my ear.

After, you mashed your Ken doll onto my Career Barbie, who lay lifeless on the bed. Her briefcase was at her side, as if she had just come home from a long day at the office. Her pencil skirt was flecked with our blood until, suddenly, it wasn't there at all.

"What are they doing?" I asked.

"It's what you do when you get older," you said, and I nodded solemnly out of respect for the two-year head start you had into the unknown world of adults.

The Easy Bake oven dinged. Pink little cakes popped out, so underbaked that they drooled batter. We doctored them up with strawberry sprinkles and fed them to each other because that's what you said happened when you got married.

"Why you wearing a bra, Lo?" I dabbed at my mouth with a leftover Christmas napkin. "It's nighttime."

"Nobody taught you anything, and that's a shame," you said. "It's not right for a girl to flaunt when men's in the house. Brings trouble."

I thought I saw you wince, but it may have been a trick of the light, the way the sun never seems to set over the prairie, how it sits still in the window for so long you forget all about night.

"I'll show you," you said, pulling at my Pocahontas nightgown.

It was ratty, long deemed unfit for sleepovers by my mother. But my commitment to Pocahontas above all the other Disney princesses was unwavering. I would not abide by her Cinderella replacement or sparkling Tinkerbell stand-in. Pocahontas's determined gaze crept up inch by inch as you lifted her to my navel.

"How's that feel?" You tugged at my underwear.

I thought of late-summer sunburns, popping a big blister after gymnastics. "It hurts," I said.

Your eyes met mine, and I saw something in them like recognition or relief, maybe. "I think that means I'm doing it right."

A barn swallow flitted by outside in a flash of blue. I draped my nightgown back over my knees, and Pocahontas seemed to wink at me in the fading light.

After the crowbar and the brain injury, my grandmother developed early-onset dementia. Her memory loss was precipitated by the head trauma but also by her depression and isolation from friends and family. My grandfather drank away what little money he earned at the steel mill and insisted she stay home at all times, except for trips to the grocery store. This was the era in which many women didn't drive, and she would make her weekly pilgrimage to the Giant Eagle ten blocks away with all four of her children in tow. Eventually, she lost her ability to speak. To her neighbors, she was "good-natured" and "quiet". To her priest, she was "dedicated" and "contemplative". To her children, she was a ghost, cutting the crusts off Wonder Bread sandwiches and silently trailing the whir of the vacuum around the house.

Eventually, I joined her in silence. I didn't speak for the three months following my third suicide attempt. She was living with my mom and me because money had run out for the home. We met in the space between words, a brush of hands as we passed the salt. We smiled at each other in the hallway, her body blooming larger with time and mine withering into a husk. I dreamt of a silver thread that wrapped itself from her neck to mine and woke with the weight of it unspooling across my clavicle.

I leafed through my Pap Pap's notebooks, finding a passage on mugwort for sleep. I ordered some online and prepared an infusion with lavender and chamomile. I slept soundly for seven nights, until he appeared in my dreams. His bald head was covered by the paddy hat he always wore, and he hobbled toward me with his cane. "I forgive you," he told me, and kissed me on the cheek. When I awoke, I was fuming. Wasn't he the one who should have been asking for forgiveness? As if I were chomping at the bit for patriarchal clemency in the first place. Not attending someone's funeral is a far cry from beating someone until she can no longer function.

Still, I returned to Pap Pap's journals, making my own notes in the margins. When I scraped my shin on the gears of my new bike, I flipped to the entry on arnica. I poured equal parts olive oil and beeswax into my makeshift double boiler and melted them together with an arnica-St. John's Wort emulsion. My skin healed perfectly after a few days of nightly application. I wondered if my Pap Pap had made this arnica cream for my grandmother whenever he hit her. And if he had, was it to ease her pain or to heal the bruises quickly so neighbors wouldn't stare, wouldn't look at him differently when they passed him in the street?

I read a friend's cards last night. Her husband had hit her for the second time. When I opened the door, the first thing I saw was her bloody lip. I liked that she didn't cover it with makeup. I've had my fair share of busted lips, and I mastered the art of concealing them with thick coats of lipstick blending into caked-on foundation. "I told him I wouldn't lie for him. It's about holding him accountable in his community," she said of her bare lip.

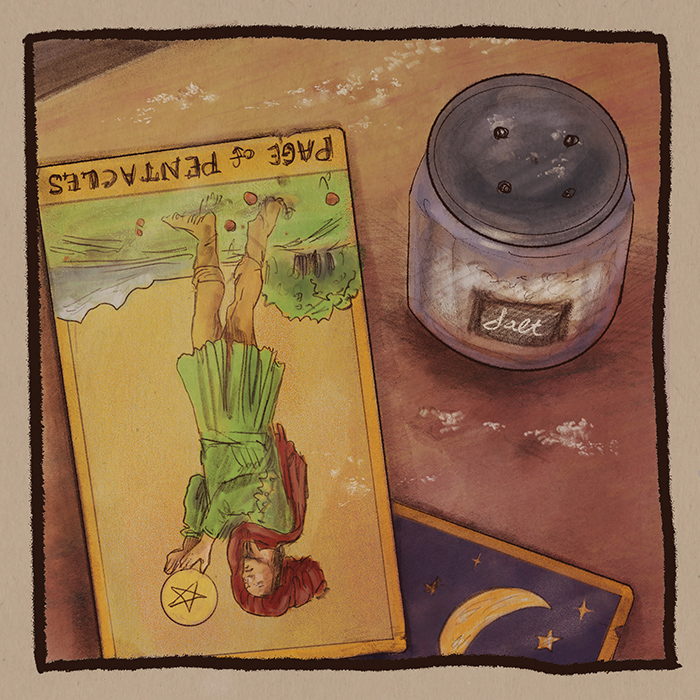

Before I started the reading, I invoked your spirit and my grandmother's. I hated to bother you, but I figured things must get boring where you are, anyway, and so maybe you wouldn't mind that much. Then I pulled the reversed Page of Pentacles—forgiveness.

"It doesn't necessarily mean forgive Travis," I hastened to clarify. "It could be about extending compassion to yourself."

Candlelight flickered across her face. She started to smile, and her lip began to bleed anew. "Can I ask you something?"

I stopped shuffling the deck to meet her gaze.

"Why didn't you ask your grandfather's spirit to be with us? It seems like he would be a good guide. He taught you, didn't he?"

"Not really. He just gave me some notebooks. And he killed my grandmother. He beat her so bad she could barely remember her own name." I set three stacks of cards in front of my friend, but she looked hesitant. "Everything okay?" I asked.

"I don't mean to be inconsiderate. It's just that in the Navajo way, you don't talk about the dead like that."

"It's the truth." I headed for the stove to put on more tea. "I don't like to sugarcoat things."

"There's a pull that draws the spirits back to this world when they hear they haven't been forgiven. Forgiveness releases them. They need that to move on."

I set our tea down and nestled the Page of Pentacles back into the deck. "Maybe forgiveness looks different for different people."

I tend to think about forgiveness in terms of understanding. I know the guy who cut me off in traffic was probably having a bad day, as we all do from time to time. I know my own father wasn't a better dad because he had no models for parenthood, only two people who barely liked each other trying to buffet a child, reasonably unscathed, into adulthood. I know my ex hit me because he was afraid of the world and of himself. None of this absolves people of responsibility, but it waters compassion until forgiveness flowers. It makes living easier.

I'm not sure if you remember, if memory functions the way it does here where you are, but we used to stand in front of the full-length mirror that your parents brought from Thibodaux, whose parents brought it from Haiti. Your aunt told us that mirrors were portals to the spirit world, and so we should always be careful when looking into one. In retrospect, I've often wondered if her advice wasn't more to ward off vanity than ill-intentioned spirits. At the time, though, we clasped palms and earnestly sprinkled salt around the mirror for protection. Your fingers over mine, a scrim of flesh around a gleaming gold gourde. A gris-gris is what your aunt called it, a talisman. We would invoke our ancestors—the good and the bad alike—and ask the portal to bring us someone to talk to, someone who would listen to us, two small girls with wobbly knees and shaking hands.

Once, we thought we saw someone. A woman with hair down to her feet. Of course, it could have just been the quivering of the candleflames or the slow wave of the maple outside. She was obscured as if by layers of veils, her silhouette barely distinguishable from our shadows. After we exchanged a look and turned back to the mirror, she was gone.

"You see her?" you asked, your fingers still interlaced with mine.

"She was there. I saw her."

All these years have gone by, and I can't know if there was a woman in the mirror, or even if I'm remembering what happened correctly. What matters is that we saw her together, that for one moment, we looked and saw the very same thing. Sometimes, I wonder what the woman wanted, if she needed something. I wonder if we could have helped her if we hadn't looked away.

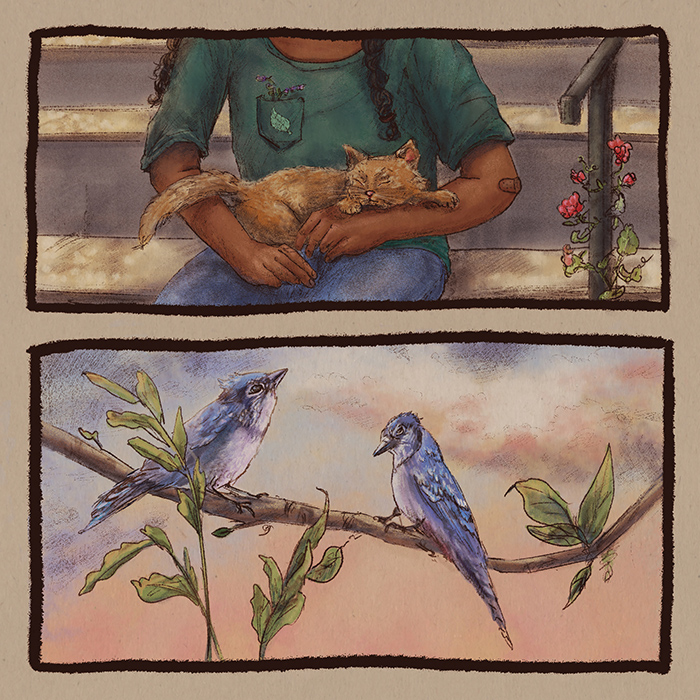

One summer after my parents divorced and my dad moved across town, my Pap Pap came to visit. He and my dad sat in the small herb garden out back as I played with my cat on the patio, pretending not to eavesdrop.

"When will she grow up already?" my dad asked. "It just takes so much to keep her busy."

"You'll miss this time you had with her one day. Remember that." Pap Pap winked at me through the sage.

My dad got up and arranged my grandfather and me in front of his tripod. Pap Pap indulged me by holding my kitten in his arms, even though he was allergic. He plopped his paddy hat atop my pigtails right as the shutter went off.

I still have the photo. It's the one I like to remember my Pap Pap by most. The way the sun glinted off his bald head, dazzling white above a swath of green. I can make out thyme next to marjoram, the suggestion of purple in the bottom left-hand corner where wild lavender grew amok. Afterward, we would plant dillweed at Pap Pap's insistence, his fingers fluttering like butterfly wings as he pulled a packet of seeds from his breast pocket.

I have to level with you. I didn't go to your funeral either. I don't really know why. I kept thinking about the night with the lemon half and the gooey pink cakes, kept thinking I should have listened to what you were saying. Maybe I was ashamed. When your dad looked at you that night from his La-Z-Boy, I didn't want to understand what it meant, but I know deep down that I did. It's the look we're taught to fear from birth, the look that says, "I can hurt you because you won't say anything." You didn't say anything, and neither did I. I didn't say anything when he yanked at your waist in the kitchen, the plastic knife you were holding falling into the sink. I didn't say anything when you showed me the blood blooming in your underwear. I didn't say anything because I didn't have the words.

I am still searching for the words.

When you died somewhere between Tulsa and Fort Worth, headed back home for a visit from college, I pictured you dropping your phone and swerving into the concrete barrier. I tried to imagine your face, tried to see if it would have been contorted in fear or staid with acceptance. I remembered you telling me that once you went away, you were never coming back. I wondered if you ever really got away, if you held onto the steering wheel and closed your eyes, maybe even remembered the way our blood commingled on the lemon slice and how we fed each other cake as if it were our wedding. When your mom told me the news, I asked what had happened. "An accident," she said but looked out the window, concentrating on a pair of blue jays sitting so still they might have been bolted to the tree branch. Your father didn't say anything, just kept his eyes trained on the TV.

I didn't go to your funeral, but I did buy a black dress. The fabric was stiff and unyielding against my skin as I slipped it on and stood in front of the mirror. I invoked my ancestors—the good and the bad—and searched for you. I said to myself, to you, "I'm listening, Lo. I'm listening," over and over like a prayer. But all I saw was my own reflection.