Saving Nary

Saving Nary

Saving Nary, Carol DeMent's historical novel about the 1970s Cambodian genocide, is both wrenching and inspirational, with some touches of humorous domestic drama to lighten the fare. The issues raised by this book remain highly relevant in present-day America, as we face another refugee crisis where idealism clashes with fear of the other.

From 1975-79, the Khmer Rouge, a Communist government in Cambodia, conducted one of the most brutal purges in modern history. About 25% of the population was wiped out through civil war, torture of perceived political opponents, and failed agricultural policies that led to famine.

The novel's main character, Khath, is a rare survivor of an infamous Khmer Rouge prison where 20,000 people were tortured and executed. His skills as a mechanic motivated the guards to keep him alive. Tormented by PTSD and his complicity with the regime, Khath only lives to find his daughters, whom the soldiers snatched away from him. With his brother, Pra Chhay, a Buddhist monk, Khath is resettled to Glenberg, Oregon. But the manipulative Mr. Sareth considers himself the leader of the Cambodian refugee community in Glenberg and sees the monk as a competitor to be ousted. Sareth preys on paranoia about Khmer Rouge collaborators in ther midst, leading to an explosive conclusion where secrets are revealed and some miracles of reconciliation occur.

DeMent, a white author, created these characters and situations based on her years of experience in Southeast Asian refugee resettlement. In the introduction, she cites numerous academic studies and primary documents as well as experts she consulted. Her research adds up to a sensitive, complex portrait of people coming to terms with unthinkable acts perpetrated against one another.

Though some white Americans play supporting roles in the plot, this is not the typical "white savior" framing that Hollywood uses to finesse the stories of people of color for a supposed majority audience. The small-town priest and the women volunteers are kind and creative problem-solvers, but realistically miss some nuances of the power struggles in the refugee community, such that their help temporarily makes matters worse. The centering of the Cambodians in their own story was something that made Saving Nary stand out from other social justice themed novels we read.

The writing could have been tightened in several places by cutting unnecessary descriptions of mundane action and of character motivations that had already been established. The judges debated whether Sareth would really feel privileged and secure enough to risk his future in Glenberg by pursuing a petty feud with his countrymen. Though he did not have the same political trauma history as the later-arriving refugees, he had nonetheless lost all his wealth, social position, and ability to return to his homeland. A few moments of fear and self-doubt would have been plausible. There was also a missed opportunity to make his shallow and snobby wife, Chea, a more well-rounded character by showing how she felt about being trapped in marriage to an unkind older man. We never saw them feel the pain of their exile. The middle section of the book dragged a bit because of the focus on this low-stakes infighting, though the amazing twists at the end made up for it.

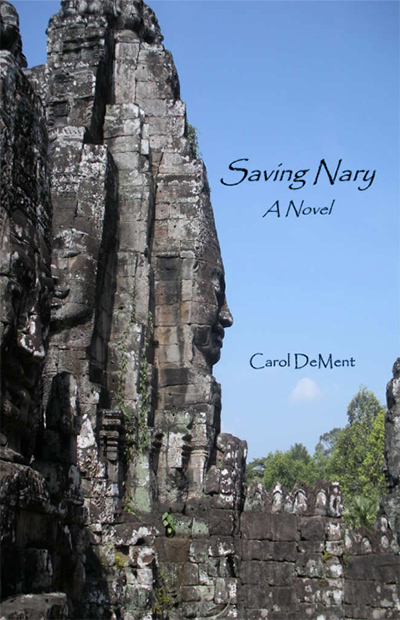

The trade paperback was nicely designed with an elegant, readable font. Proofreading and editing were generally good. The cover photo of an ancient Buddhist stone temple is attractive and intriguing, and the jacket copy concisely conveys the essence of the story. Saving Nary would be a good movie adaptation or book club read, with appropriate trigger warnings for the descriptions of Khmer Rouge atrocities.