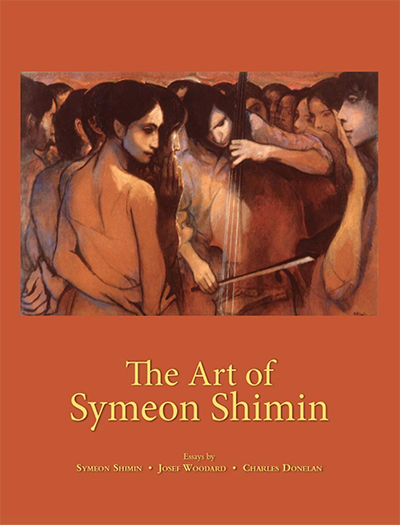

The Art of Symeon Shimin

The Art of Symeon Shimin

Public recognition for an artist, whatever his talents, may hinge on the alignment of his style with the zeitgeist, as well as whether he has financial security to keep developing his craft while waiting for that breakout success. For 20th-century social realist painter and commercial illustrator Symeon Shimin (1902-84), these external factors hindered his ascent in the art world. The Art of Symeon Shimin, a retrospective by his daughter Tonia Shimin, makes the case for greater appreciation of his skills and cultural significance.

Shimin's Russian-born Jewish family emigrated to Brooklyn in 1912. In the autobiographical essay that opens the book, he reflected on the influences that formed his dark and dramatic visual style and his lifelong interest in portraying the dispossessed. His father, an antique dealer, secretly aided the resistance to the Czar. Reading Tolstoy as a teenager, Shimin resonated deeply with the novelist's spiritual ideal of a simple and generous life. He wrote of his original ambition to study music, forbidden by his family as too impractical. This tension between art and survival would shape his future career in America.

Shimin's most notable achievement was the mural "Contemporary Justice and the Child" for the US Department of Justice building, created over 1936-40. As a commercial artist, he created the original poster art for the 1939 film Gone with the Wind and King Vidor's 1959 epic Solomon and Sheba. He also illustrated numerous children's books.

In the tense, knotty, tightly packed figures in Shimin's fine art paintings and drawings, I saw a resemblance to the work of Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), another early 20th-century artist who memorialized the suffering of the working classes. Like Shimin, she was left behind by the art world's turn toward abstraction, but the emotional power of her work is undeniable. I also saw similarities to Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), another American muralist devoted to depicting the common man.

The Art of Symeon Shimin includes essays by Josef Woodard and Charles Donelan contextualizing the artist's work. Woodard notes that Shimin visited Mexico in the 1930s and was influenced by the social realist muralists there, such as Xavier Guerrero. Shimin's social circle in 1940s Greenwich Village included many of the famous abstract artists of his day, but he refused to follow those trends himself.

I would have liked to know more about the artists who did serve as role models for Shimin's stubborn devotion to realism. Biographies for the essayists were also unfortunately absent. Project curator Tonia Shimin's voice was not prominent enough. It would have been nice to hear a little bit from her about the choices she made in selecting the artwork and critical essays for this book, and even some anecdotes about the artistic milieu she grew up in, as a counterpart to her father's personal reflections.

The book design and image reproduction quality were both outstanding. The font was easy to read, with few if any typos. The glossy, sturdy paper and professional layout of images made this book indistinguishable from something you would buy at a major museum's gift shop. The opening essays were well-illustrated with photos and images relevant to the text, setting up the narrative to make sense of the book's second half, a catalogue of Shimin's major works. We had no doubt that this was the top art book of 2022. Hopefully this is just the beginning of a renewed critical interest in Symeon Shimin's achievements.

Read an excerpt from The Art of Symeon Shimin (PDF)

Buy this book on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Pathway Books. For wholesale orders, please contact Pathway Book Service, Ingram, or Baker & Taylor. See also this listing at Edelweiss.