Who Is Jo March?

Who Is Jo March?

Lin Haire-Sargeant foregrounds the queer subtext of a classic novel in Who Is Jo March?, a Civil War espionage romance whose style recalls Louisa May Alcott's other career as an author of pseudonymous melodramas.

As long as there have been Alcott fans, there have been readers who demanded an alternate ending for Jo March in Little Women. Few believe that the feisty, tomboyish heroine should have married the moralizing, unsexy Professor Bhaer, who shamed her into burning the pulp novels she wrote.

Most of us shipped her with Laurie, the flamboyant young man next door, whose marriage proposal Jo unconvincingly refuses in the official storyline. Lesbian playwright Carolyn Gage's Louisa May Incest imagined Alcott forcing her character into marriage with a father figure in order to occlude her own trauma. The 1994 film with Winona Ryder cast the foxy Gabriel Byrne as Bhaer to make Jo's choice believable, while the 2019 remake by Greta Gerwig left the "real" Jo unmarried, and revealed the Bhaer storyline to be a fiction-within-a-fiction required by the male publisher of Jo's novel, Little Women.

Haire-Sargeant's Jo occupies a liminal gender space, and reflects on it throughout the novel in a complex and sensitive way. On the surface, she merely follows in the footsteps of other pre-modern heroines who disguised themselves as male to have adventures outside the domestic sphere. But like the real-life Civil War soldier Albert Cashier, who was assigned female at birth, Jo's masculinity can't simply be reduced to a matter of convenience. She inhabits her male clothing, body language, and social role with genuine relief and joy. And yet, once freed from trying to imagine herself as a wife, she realizes she loves Laurie and wants to win him back from the hyper-feminine actress (and Confederate spy) who has seduced him away.

Lacking a modern taxonomy of queerness, Jo doesn't have the words for her identity crisis, but the absence of labels allows her to move between genders as required to assist the Union cause. The author authentically depicts not only the physical feelings of transmasculine or butch dysphoria, but the way that it separates you from other people because you're always in disguise.

Meanwhile, Haire-Sargeant gives a dark but plausible twist to the character of Beth, Jo's saintly invalid sister. The Victorian romanticization of early death has taken rather too much hold on Beth's imagination. Her new storyline brings out the suppressed anger and despair of women who grew up believing it was better to die than lose their innocence.

The writing sustains the tone and style of the 19th-century original, with no notable errors or awkward passages. I was frequently moved and always entertained. The plot could be considered too melodramatic at times, but that was also in keeping with the Victorian genre pastiche. It was not clear enough, for my taste, whether Jo continued to live as male at the end of the book—though the detail that she and Laurie moved to San Francisco could be a clue!

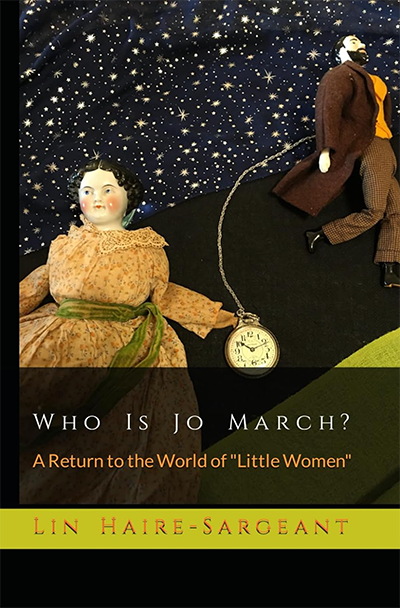

The book design was plain inside but readable, with good line spacing and print size. The cover image of vintage porcelain dolls was intriguing and gave the right period vibes. I'm sure that Who Is Jo March? would have a large queer fan base as a movie or TV series, given the reliable demand for Little Women adaptations.