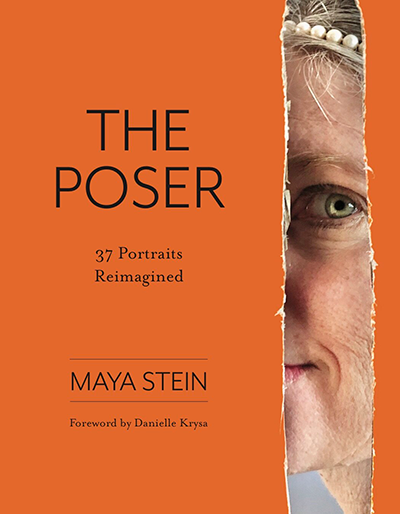

The Poser

The Poser

The COVID lockdown of 2020 felt like a throwback to an era of home-based artisanry. To balance our sudden overdependence on screens, and make up for the lack of professional public entertainment, people baked sourdough bread, landscaped their yards, and shifted from being consumers to creators of art. (These leisure activities, of course, were not always available to those on the frontlines of healthcare and other essential industries.) Re-enactments of classic paintings trended on social media. Maya Stein's art book The Poser: 38 Portraits Reimagined takes a deep dive into this pastime, pairing her interpretations of works by contemporary women artists with the artists' essays on life in quarantine.

Whereas the "museum at home" challenge popularized by the Getty Museum focused on well-known classics, Stein decided to showcase living artists whose work deserved a wider audience. Dialoguing with these women about her re-creations was an additional way to break through everyone's isolation.

She writes in the introduction, "I found myself investigating visual art in an entirely new way; out of the restraints of a museum or gallery visit, where I could only stand back and observe, I was embodying the work, becoming the canvas." Her one- or two-page essays accompanying each re-enactment photo contain autobiographical anecdotes about why the original work spoke to her, as well as the comical challenges that Stein and her wife, Amy Tingle, faced in finding appropriate props around the house.

Their creative choices included a unicorn Halloween mask for Ilona Niemi's lizard-headed person in "Deflated", and a brassiere worn on the head to replicate Naomi Devil's mouse-eared fetish cosplayer in "Yolandi". Since Stein's available props often bore only a passing resemblance to the original items, she concentrated her skills on capturing a painting's pose and mood.

The Poser prompts reflection about where an artwork's essence resides. My co-judge Ellen LaFleche commented, "Stein's strength was honoring the gestalt, soul, and spirit of each portrait. Her re-creations were so powerful because each portrait was a melding of two people and their artistic sensibilities."

Taking the book as a whole, we felt that the text started to overwhelm the artwork. The artists' statements became repetitive. We didn't need all the descriptions of their workspaces. These essays could have been pared down to highlight the most interesting aspect, which was the inspiration for the portrait and then the artist's reaction to Stein's version. Ellen commented, "I couldn't help being bothered by the preponderance of artists' statements expressing delight in the pandemic because it gave them solitude and extra time to create. As a writer, I understand that point of view 100 percent, but it got to the point where the suffering of the pandemic was being ignored."

We also wished for more diversity of portraiture. There were few artists of color and no self-portraits of older women or working-class characters. Ellen and I went back and forth on why Stein, an older white woman, selected this limited demographic. I wondered whether she was concerned about cultural appropriation and edging into blackface territory, whereas Ellen felt confident that Stein would have had the skill and sensitivity to collaborate respectfully with nonwhite artists.

The art reproductions and photos in The Poser were high-quality, with good resolution and vibrant color. The typeface was stylish and legible, and there were few errors. The paperback book's binding was too tight, which made the cover creased along the spine after reading. The Poser breaks the fourth wall between artist and viewer in a thought-provoking way that will give the book resonance beyond the peculiar historical moment that birthed it.