A China Story

A China Story

Every contest cycle, a category emerges that has stronger entries than all the others. Last year, the strongest category was poetry. This year, by far, the strongest category was memoir. To earn recognition in memoir this year is a distinction worthy of special praise.

Ying Qian's A China Story: Growing Up in Mao's Cultural Revolution is a page-turner that I could not put down. The flawless writing, coupled with the compelling story of oppression under Chairman Mao's Cultural Revolution in China, kept me awake for several nights because I had to read one more page, and then another. The juxtaposition of the author's beautiful descriptions of Chinese flowers, trees, and landscapes with the horrors of mass murder and torture, mysterious disappearances, and neighbors turning in neighbors for slight or suspected offenses, makes this entry a tour de force.

Qian is an 8-year-old second grader in Beijing when the Cultural Revolution begins:

Old songs were banned. We were not allowed to sing my favorite song about a little rowboat floating on the lake and the cool breeze caressing children's faces anymore. Now we sang: "big machete chops down on foreign devils' head" or "pick up our pen and use it as a knife or a spear".

Qian's beloved Teacher Li must now inculcate her second-graders with propaganda and force on them complete devotion to Mao. Oppression escalates: school children abuse and insult their teachers, professors are forced to walk around campus with nicknames written on their backs: Giant Poison Snake Wang, Old Cunning Fox Xu. People considered members of the bourgeoisie disappear. And disappear. And disappear. Qian's two brothers are forced to take jobs away from home. Qian and her mother, a chemistry lecturer at a nearby college, are forced to live in a tiny apartment with another family.

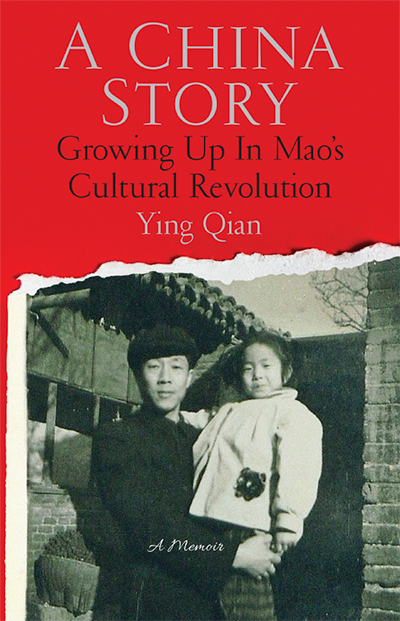

Qian's father, an expert in explosives, had disappeared when she was two. The memoir begins and ends with the mystery of how and why her father disappeared.

(Spoiler alert and trigger warning: his expertise in explosives is used in efforts to create a Chinese nuclear program. Some of the scenes of torture are devastating.)

The horrific fate of Qian's father is revealed piece by piece. Unexpectedly, he is allowed to return home to Beijing for a few months. This vacation brings much joy to young Qian and her mother; this unexpected happiness is symbolically shown by Qian's descriptions of the sensual beauty of the Chinese landscape she sees around her as the family enjoys a slow row-boat ride around a lake.

The story arc of her father's fate is the structural backbone of the book. Qian returns to China many years after settling in the United States. In a Beijing hotel room, she receives documents from family members that reveal how and why her father died.

Of special interest are the examples Qian uses to show how she and her classmates developed unconditional devotion and loyalty to Mao, how she slowly—ever so slowly—began to privately question this process of inculcation, and how she sought escape by becoming a college student in physics in the USA.

There are minor issues from a judging perspective. There are very few errors. The style is a bit formal at times, but a pleasure to read because of its impeccable editing and grammar. Qian mentions in a short paragraph how she met her future husband in America and bought a house with him. That is all we learn about her husband or marriage. Because I cared so deeply about Qian at this point, I wanted to know about their life together. However, I suspect that privacy was an urgent issue and respect her choice to keep her marriage out of the book. I am puzzled as to why this book has not been picked up by a major publisher; it tells a necessary story that deserves to be widely marketed and read.

The book has a strong binding with readable font and comfortable spacing between lines. The front and back cover are red, the perfect symbol for this must-read account.