Ghazals Connected as Though Cargo Freights

Ghazals Connected as Though Cargo Freights

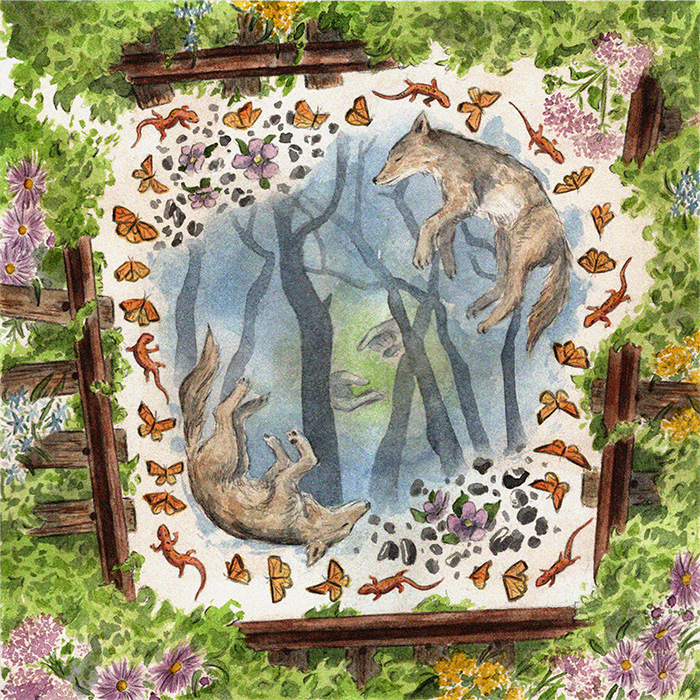

Illustration by Rowan Fridley

I.

As a child, my mother boosted me into a dumpster of damp discarded library books. I fished out

limericks, and Langston Hughes, and stack after stack of Hardy Boys. Years later, when I came out

to my mother, behind a closed door, I cried like a wolf. I didn't know it then, but there are queers all over

every forest, tucked in hunting blinds, hands huddled around portable propane heaters. Their hideout:

camouflage and venison jerky traded around like love letters. But even Pennsylvania folk in love are taken

by windstorms. When I say wind, I mean debris, and when I say debris, I mean the Oxy scripts handed out

once every two weeks, by a doctor in each and every county. I remember those car rides with my father—

me and my sibling sweating in the back, asking for Burger King, or to turn up U2's Beautiful Day, or to get out

and stretch in the Salvation Army parking lot. My father was named after his father, and his father named

after his. Peter, from Latin for stone. Too stoned and swerving. Every headlight on this backroad is burnt out.

II.

When my mother was a young mother, she would sunbathe naked on the porch. Personal planes would flyover,

lower and lower, dangerously close to the treetops. As she bronzed in baby oil, I searched for four leaf clovers

and thought about all the girls I had already decided I loved. I would whittle them tokens of affection and hope

they might finally see me. Just after I made my body angular enough to stop bleeding, I had my first sleepover.

We talked all night, and right before bed, we traced one another's lips with our pointer fingers. In the morning

we were silent but took pictures of one another laying dangerously across train tracks. Tenderness boils over

if you're not careful. Tenderness is all over the stovetop. Tenderness is two girls in love but unable to say why.

Once, I climbed a trestle and threw wildflowers into coal freights as they rattled by, one for each undercover

trans child in my hometown. You should know that I would save them all if I could. When I rolled up my sleeves

and became a boy, I didn't lose an ounce of gentleness. So, what's your new name? It's not over until it's over.

III.

The Alabama Amtrak whistles each night, loud and bossy through the kudzu, on its way to New Orleans. Take

the Crescent Line and all you see is green and porch swings. When I made a home of the South, I was taken

under its arm, like any other cousin. I was invited into dart leagues and nobody much cared about my body,

only that I could throw, even while drunk and bumpy with mosquito bites. I've made so many mistakes

in my life, but none when naming my friends. When I was a kid, after each rainstorm I'd search for fire newts—

bright and humid animals. When I was a kid, I tinkered with the tin foil antenna, and envied the Undertaker's

muscles. What boy didn't? So much about the world has changed since then, but I still learned the most useful

thing you can do with your time is throw milkweed for the Monarchs and keep your friends close. Please take

my word for at least that. Each morning, I pray to a floral god; I pray for my friend's house plants and I pray

for their growth. Friend, if you need me, I can kiss your cheek, and suggest a train you might like to take.

IV.

Even though the only blood I've ever had on my hands is my own, it's still hard to sleep. When my father

slept, he slept with his eyes open, the whites of them glowing in the almost moonlight. So many fathers

are worried that their families will escape in the night, cut their losses and just run. You might think I'm angry,

but I'm only angry when the engines won't start, and we need them to. Someone should tell our forefathers

about all their indelible and violent mistakes. Someone should tell them about all the American children in danger

and bleeding. Tell them each botched prosecution is another hollow point thrown in a fire for later. So many fathers

know they've done wrong, but won't admit a thing, and instead roll their trucks drunk into another cornfield. Instead

blame their wives, who were at home the whole time. Instead say, Look at me when I'm talking to you. I'm your father.

Somewhere, on a property that once belonged to my family, a light green house is rotting fast into the hillside.

The "Candrilli Construction" sign, crooked and rusty. Teens break in to tell ghost stories. They still name my father.

V.

My mountain had no wolves but plenty coyote, plenty of paper birch taken down by the wind. I used to name

every fallen tree, each coyote mounted on the wall. Now, when I wake, I wake next to my partner. I roll their name

into the bed sheets—like a color poured into a glass of water. Our life is full of plenty and we built it this way.

We plot our future on graph paper and fill it in with scented markers. We draw up a list of brand-new surnames

and try them on like you would a new pair of high tops; everything chafes at first. But there's no need to worry.

Around here, the waves aren't made of porcelain. So, don't worry about them breaking. I can't wait to name

all of my partner's kindnesses as we deliver our vows: all the milkweed thrown, all the lights strung and floating,

all the Jiffy Pop and tenderness. And perhaps, at the wedding, I'll mention that nobody needs their deadname

at all. My father was named after his father, and his father named after his. I named myself. Perhaps destiny

is a myth, and perhaps this myth is all we have. It's time to call me by my name. Please don't miss a sound.

First published in Ploughshares, Vol. 47/1