Sylvia

Sylvia

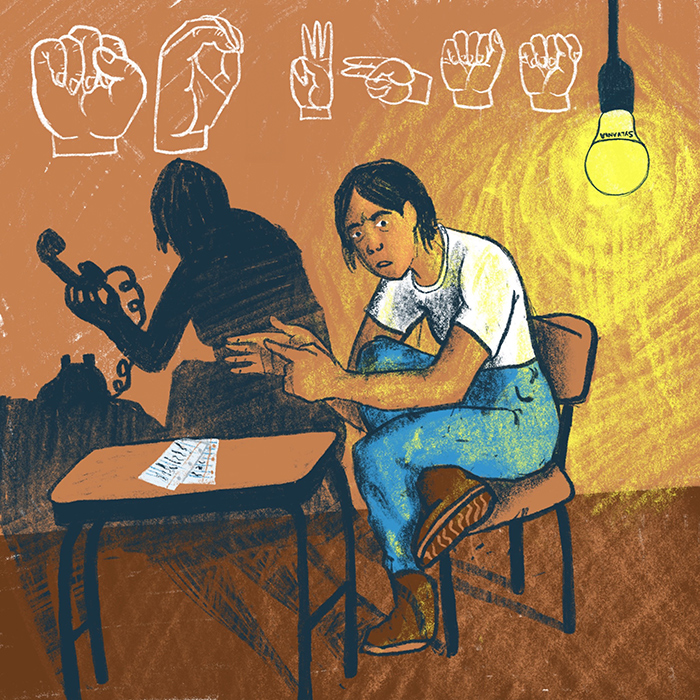

Illustration by Kimberly Edgar

I never saw her smile—not once—not in all the months I would come to know her. Her eyes held something. I didn't know what. It wasn't vacancy. It wasn't sadness. Maybe it was rage—maybe hidden, seething rage. Maybe that's too strong. She was the most homeless-looking person who had ever walked into my deaf adult evening class. The jacket she wore the first night had the unmistakable look and smell of Goodwill. Her slacks were dark plaid and polyester, and the navy blue of them seemed to seep up into a haze that enveloped her, extending outward into an almost visible aura around her edges. Her hair was dark, her eyes were dark, and as she stood in the doorway, she seemed dark...and lost. She had the look of a child who had just awakened upside down in an overwhelming large bed. She was wearing neither hat nor gloves that night, but, oddly, she wasn't shivering.

And silent. She was definitely silent. Not the silence of the other deaf students in my class. Not the silence that is willingly broken to make hearing people understand. This silence was different. It seemed purposeful, like the closed-lipped silence of a person holding something like liver in their mouth that was too disgusting to swallow and too large to spit out.

She arrived late that first evening, and I could feel myself trying to smile graciously for what I knew would now be, at the very least, a ten-minute disruption. It wasn't anyone's fault. It was a deaf culture thing—a social phenomenon that swoops in like a wildfire in a forest parched by the need to be understood. Most of the students in my class had attended the State Residential School for the Deaf back in the '60s. Seeing an old classmate now, some 30 years later, would start a blur of concepts that would flash laser-like across the room on visual strings that begged to continue in vibration. And in the blur, all news would be told… Remember JK, senior year?... new job... g-r-a-p-h-i-c-d-e-s-i-g-n… Really? ... You? Twins? Cool! (the latter signed like deaf kids in the '60s used to sign neat.)

I didn't mind the anticipated interruption. I was no longer the young "hearie" teacher who would catch but a few signs here and there, missing the subtleties, like a tourist in a foreign land. I was in the field long enough to feel one with this culture like the American Jesuit in Guatemala giving his homily in Spanish… the British importer in Beijing ordering lunch in fluent Mandarin. I had even dreamt one night in only signs.

But there was no interruption this night. No flashing lasers across the room…only sign-less stares at the reticent navy-blue figure who still stood in the doorway.

"Welcome," I signed, "Come in." I hoped I was still smiling as I gestured to a vacant chair.

"Your name?" I signed as she sat.

Only three finger-spelled letters later…"s"...stop..."y" stop..."l", and I knew and my class knew, our group dynamic was about to change. She had none of the deaf-style fluidity of fingers that makes unspoken words become calligraphy in space and time. Some thirty-five years old and she was clearly new to signing. "Perhaps she had been late-deafened," I thought. Could be hard of hearing. Raised orally without signs? Possibly. "S-y-l" continued, struggling for the next letters like a child at the piano looking for the keys. In the slow-motion of the waiting, my mind started playing with the possibilities…Sylvester? I laughed to myself. Sylvania…yeah, like the light bulb!… No, obviously it must be Sylvia… Come on, Sylvia, paleease get it out.

She continued: "v-i-a".

"Nice to meet you, Sylvia. Do you have a name sign?"

Sylvia's eyebrows knit as she just sat and looked at me.

Name sign! I thought. Damn, she doesn't even know what a name sign is. I turned to the class, hoping for help. One by one, my students spontaneously illustrated the concept of their individual name signs; Sylvia barely blinked in response to their efforts. Finally, we agreed Sylvia would now be an "s" at the temple and hoped she caught on.

Class that night felt long. Sylvia's lack of understanding was forcing me to switch back and forth from an ASL deaf-preferred signing structure to a more hearing mode of voiced Signed English, hoping she might understand with lip-reading cues.

And I resented it. For the last two weeks, the profound deafness of this particular group of adults had propelled me to a peak experience. We were signing adult to adult, not teacher to child. And I was "in the zone", my skills being challenged to their capacity. Two fingerspelled letters here, and I would know the word…a flicker of movement there, and I could understand who did what to whom and why. Three hours of "saying" without speaking…three hours of connecting and feeling useful. I was the privileged hearing person let into a secret world, and now it had to change because Sylvia couldn't understand!

I was thankful toward the end of the evening that Joyce, the director of Deaf Bridge, stopped by to see how the students were doing. I could finally sit down and let her take over. When she finished with program updates, I dismissed the students and Joyce stayed to talk.

"I see Sylvia showed up," Joyce started. "She appeared at my office to register this afternoon."

Appeared! It echoed in my mind. What an accurate word for how she entered my class.

"I haven't seen her other sessions," I replied. "She doesn't seem to understand much…or even lip-read for that matter. Just recently became deaf, I take it."

"No…uh, no. It's not an age or progressive thing. She's been profoundly deaf from birth. Her sister told me."

"What!? For God's sake, Joyce, she doesn't sign or even lip-read. Where's she been all her life...in a cave? It's the '90s, Joyce, not the 1800s! She's well past thirty. Not one deaf student in the class seems to know her. Don't you think that's just a little odd?"

As I looked up, Joyce continued explaining that Sylvia's sister was the one who had found the Bridge. "She can never help Sylvia register because she plays cello or violin for some philharmonic orchestra. Only flies in and out of town every so often."

"How ironic is that?" I interjected.

As we walked out into the evening chill, Joyce explained Sylvia was raised down south somewhere… "Arkansas? Tennessee?" She didn't know. "Shows up for class every other year. Great writing skills though."

"That's what I mean, Joyce. I had her write a few sentences. No dropped -ed or -ing endings... Perfect subject-verb agreement. It's like she grew up hearing."

"Talk to her sister. Trust me, you'll have the chance. She's called Sylvia's teachers in the past. I'll give her your number if that's okay."

I thought phone calls in the evening were over when I stopped teaching little ones, but I replied, "Sure." The mystery of Sylvia was too intriguing to say no.

The next week, the wind off the frozen lake howled only to the hearing, but chilled everyone indiscriminately. Still, there was full attendance at the Bridge. Even Sylvia showed up—again no hat, no gloves, no shivering. Again, she simply appeared almost ghostlike, as if up from the floorboards or down from the ceiling. Again, she frowned through the first hour of idioms and verb tenses. At break time, the other students filed past her, fingers chattering. Sylvia stayed seated at the end of the pressed-board tables, alone.

"Break time," I mouthed larger to her than I wanted.

In slow, straight "hearing" English Sylvia signed, "I-am-fine."

It felt unnerving to scurry about finding transparencies for the overhead projector and checking papers with one silent, staring student left in the room. I forced the feeling of discomfort somewhere outside of my body and pushed the guilt for not engaging with her down to some place I knew I'd be visiting later. When I arrived home after class late that night, the phone was ringing. I answered with my coat still on.

"I'm Sylvia's sister. Joyce gave me your number. I'm Diana." Her voice had the throatiness of sophistication, and I could visualize her playing the violin in an elegant long-sleeved black crepe.

I tried to not sound tired.

"Ah...yes. So happy you called," and I jumped right in with, "I've been wondering about Sylvia."

There was something cold and direct in her "Why?"

"I mean her educational background. She doesn't seem to understand when I sign."

"She hasn't had much," and there was that kind of silence that the controlling leave open for those not brave enough to leave it alone.

"Hasn't had much...schooling?"

"No, not much schooling. We're from Arkansas." She continued with lengthened vowels that would seem to confirm that fact. "I wasn't around much while Sylvia was growing up, so I don't exactly know. I think she started school and then stopped."

"Oh, I see." But I didn't. Not around much? But I was too tired to go there. New subject. "I don't exactly know our goals yet."

"She wants to learn more signs," Diana offered.

"Yes, I see. But...I'm wondering if a class in basic sign language, to begin with, might be a better match for Sylvia right now. Our class focuses on the refinement of English writing skills and discussions of socially relevant topics." I felt a twinge of guilt for wanting my "deaf only" class back to myself.

"No," she answered simply. Her voice was firm and seemed to echo in a room that sounded hollow to me, perhaps a sparsely furnished apartment she rented when in town, I surmised. Again, there was the silence that seemed to force my response.

"Well, she doesn't seem willing to mix with the other deaf students. She sits alone at break and doesn't go out to the hall to try to mingle or get a soda or anything."

I thought I had misheard the sister's next response.

"She doesn't know how to use the Coke machine."

"Uh..." I scrambled for meaning. "Excuse me."

"She can't count money. She doesn't know how to use the pop machine. I want her to learn that."

I was dumbfounded at the concept. It was obvious that despite her homeless look and novice signing, Sylvia was in no way lacking in mental capability; her written responses to my writing assignment clearly indicated that. How does one get to be some 35 years old and not know how to use a Coke machine? The other students in my class might have been deaf, but they were only deaf. Bob was taking night classes because he had an appetite for politics and wanted to discuss articles in Newsweek and Time. Bonnie was the mother of hearing twins. Her toddlers could sign and speak and wore Nike tennies and little jeans from the GAP. She wanted to learn to sign the nursery rhymes she had never heard as a child. Richard, the graphic designer, studied at the prestigious National Institute for the Deaf in Rochester, New York. His new role as President of the Open Door Deaf Club would require an understanding of Robert's Rules of Order.

I tried to explain to Diana the writing and vocabulary goals I had for this class, but she was insistent.

"Sylvia needs to learn things. Surely you could find some time…"

Of course, I could. What could be so hard in teaching someone to get soda from a Coke machine—someone who didn't understand a single word I signed or said or mouthed or mimed—during the one break I had all evening!

Instead, I answered, "I'll give it a try."

"Next week?"

God, this woman! "Yes, next week."

I started the following Monday's class with a discussion on writing autobiographies. It would keep the group working while I pulled each person out to work on individual goals. I saved calling Sylvia to my desk until close to break time.

"Sylvia, your sister called me. She said you'd like to learn to use the Coke machine."

"What?"

I wrote what I had just said in her notebook.

Sylvia reached for my pen. Under my sentence, she wrote, "My sister called you? What did she want?"

"Yes." And I pointed once again to the sentence I had written.

Sylvia nodded like an obedient child.

During break time, Sylvia and I walked to the vending machine area. I took some quarters out of my pocket. "Twenty-five," I signed "fifty, seventy-five." There was the familiar look of "Sylvia-confusion", but I proceeded. I pointed to the slot and motioned her to put the coins in. She wouldn't take them from my open hand.

Oh Lord...

"Okay, Sylvia, I'll go first." I placed the coins in the slot. I heard the soda drop below. Sylvia still stared at the coin slot. I pointed down to the tray, grabbed the can, and put it on the floor so I could continue signing. I took out three more quarters and handed them to Sylvia. Again, she wouldn't take them.

Okay...start her off...damn...this is taking so long.

I motioned for Sylvia to press "Push Here", but hadn't expected her reaction. There was fear in her eyes and she backed away from the machine as if it would harm her. "It's okay, Sylvia." After looking into her eyes, the task seemed to take on more seriousness and compassion overtook my impatience.

I pointed again and mimed the action of pressing.

I was hoping I didn't look like some missionary in Africa in the '20s delighted with myself for exposing this soul to civilization, but I might have had that look. Sylvia simply looked confused, but she came closer.

"It's okay, Sylvia, press."

The Miracle Worker first hit the cinema long after I had declared deaf education as my major, and I never went into the field to be Anne Sullivan. That night, however, as Sylvia pressed the button and I pointed to the tray where she hadn't heard the soda come out, I felt as if I was at the pump spelling out w-a-t-e-r. It was a fleeting feeling because I was the only one sharing in the triumph. Sylvia never reacted, never smiled. Her frown lines only shortened a bit as she walked robot-like with her soda back to the room.

I was hoping Diana would be out-of-town playing her fiddle or whatever in some city far away because I was too exhausted to rehash the evening. But no, again, the phone was ringing as I walked in the door.

I was actually excited to relay tonight's victory. "Diana, yes. So glad you called. Sylvia learned to use the soda machine tonight!"

I suppose I expected back a "Great, fantastic, thank you, Ellen. So nice of you to take the time."

Instead, Diana simply responded, "Good," and not taking a breath added, "She needs to learn how to ride the bus."

Oh brother! Will this woman never relent? I felt like echoing Dr. Leonard McCoy's voice, "For God's sake Diana, I'm a teacher of the deaf, not a social worker!" And the concept of social worker became the new rope I grabbed.

"You know, Diana, I would be more than happy to set up a meeting with you and Sylvia and a social worker."

But Diana couldn't meet us at class, she said...her "schedule and all" made it impossible.

I suggested a future Monday since she seemed to be able to call on Mondays!

Diana then raced her response along some convoluted trail of logic paths that circled back and around and lost me somewhere in the middle. I abandoned the social worker idea and ended up capitulating once again to Diana's plan. I would try to unravel the Metro bus schedule myself, I promised, and later would help Sylvia read it. I would have preferred teaching gerunds and participles.

Sylvia missed class the next week, and I was glad. As I mimed turning an invisible lock near my larynx, the sign for not talking, a collective dropping of my students' shoulders seemed to take place simultaneously. Like a secret member of a special club, I could now sign silently, fluently, to my deaf-only students. Everything flowed that evening and I felt released and connected, the way lovers do when it's good.

The next week I signed, "Welcome back," as Sylvia slipped in after class had begun. Students were finishing their autobiographies, and I was introducing "Little Bunny Foo Foo" to Bonnie for her twins. Sylvia read her assignment and got busy writing her autobiography.

Just before the break, I walked over to her desk and signed, "Finished?"

Still stoic, Sylvia nodded her head and motioned down to her paper. I pulled up one of the folding chairs and started reading. Her written English was simple, but somewhat straight (as teachers of the deaf like to say). It would need only minor corrections; I could tell that from the first two sentences. I decided, therefore, to read on for content only. It was a decision I wouldn't have had to make, for the content surpassed any notice of grammar or punctuation errors. It was the most shocking content I had read in fifteen years of teaching.

I was born in Arkansas. My mama died when I was six. I think in a fire. I had two brothers. My first brother drowned in a lake. My father was yelling at him. I was in the boat. He fell in. John drowned.

I was aware of my head moving back and forth to retrace the page as if reading the sentences again would change their meaning. Sylvia lowered her head to look into my eyes as you'd look under a shelf to see why it was not seated properly. She knew the sign most hearing people use for "what" and signed it under my face three times as if I had found some spelling error that she was sure she hadn't made.

Not looking up, I wiggled my fingers to sign "wait, wait" with only one hand and read on.

My second brother died from being shot in the head. There was a lot of blood. I saw pieces on the floor. I saw it. I think that was his brain. I went to the hospital. He died. I want to learn sign language.

Is this possible? I looked at Sylvia. Her face was impassive, stoic, resigned; and in that incongruity there was congruity, and I had to assume the sentences were true. I could feel my chest release the breath I had been holding. I told the other students to go on break and I sat down and looked directly into Sylvia's eyes.

"What?" she signed again, "What?" more insolently now, like a teenager asking, "What did I do this time to get me in trouble?"

I looked in the pools of black-blue tar, looking into mine.

"Sylvia, I'm so, so sorry." The "s" of sorry pressed the center of my chest as it circled slowly over and over.

Sylvia's eyes became opaque, and her frown furrowed deeper, in apparent confusion.

"Why? Why are you sorry?" She signed every word.

Perhaps "sorry" made little sense to her in this context, I reasoned. I tried again.

"I mean, Sylvia...I'm sad," and I mimed pulling down an invisible mask of my face. "I'm sad this—this all—happened to you."

Again she signed, "Why?" as if she was becoming irritated, and for some reason, I could imagine her voice. It would be a low, raspy voice, I thought, with a sarcastic edge of inflection.

"This, Sylvia." I pointed to the paper. "This!" "Death." I signed it again. "Death...your mother...fire." And again... "Death...your brother...drowned," and again "death, your brother shot." "I'm sad all this death, death, death, happened in your life."

Sylvia's frown lessened. She moved back to the support of her metal chair as if relieved that was all.

"Why are you sad? Don't be sad." She shrugged her shoulders as if the story were about an insignificant sliver she had just described. She shrugged once more and fingerspelled "s-o". "So? So what? So nothing. That's life. Don't look at it and it will go away."

The words she signed felt ice-cube cold with rigid straight corners—words, I thought, practiced over and over again, to cool hot grief. And the words in sign slapped me in the face and chilled my blood, and froze the moment in my mind.

I needed to explain what was most likely evident in my face.

"Sylvia, do you know that most people don't have this...this death...all this death...in their lives... Some death, yes, but like this? No."

For the first time, Sylvia looked scared, and I stopped. Somehow I felt like I was tugging on something fragile. And who are we to be so careless as to break the silken thread that holds someone together?

Coming home from class that Monday evening, I was spent. I went to the fridge for the Chardonnay without even taking off my coat. As I reached for the glass, the phone rang. Diana barely waited for my "hello" before saying, "Sylvia needs to understand the bus schedule."

"We went over that schedule several times, Diana. It's just not meaningful to her."

"She needs to get to 55th Street."

I heard 55th Street but didn't have time for details. "Yes. Well…" I shifted the conversation. "I want to talk to you about something Sylvia wrote tonight, Diana, an autobiography. I want to discuss that with you."

"Why?" I could hear her clear her throat. "What did she write?" She cleared her throat once more.

I hadn't put my briefcase away and quickly found Sylvia's paper and read it to her sister.

At the end of Sylvia's essay, Diana took a long breath that seemed to calm her voice and replied, "It's true. That's all true. But it's only the half of it." She then began a story that seemed to belong in a movie no director would be daring enough to put on the screen.

"My father abused Sylvia from the time after my mother's death all through high school. It was August when we moved to Little Rock. He'd bought a small farm and kept her at home. He never registered her for school."

"Then she never went to school?" I asked.

"I can't remember. I think she did, some days, I think. I don't know. I wasn't there."

Wasn't there! Again. I was silent as my mind scrambled to fit those pieces together. It was Diana who filled the space that would give me the clue.

"He'd have sex with her in her bed and then go out to the fields. I think she was seven. He'd lock her in the closet so she wouldn't run away. There were wires on the doorknob, electric wires."

I was getting sick to my stomach as the possibility of causation came to my mind. I could make no sound to even acknowledge I was hearing this story. Diana continued.

"He rigged it up so that if she tried to open the door, she'd get a shock. He left a light on, though. Thank God, he left the light on. There were books my mother had. There was a card with finger spelling that someone gave me at the State Fair one year. She would lie on the pile of shoes and dirty clothes and look up at the light bulb and onto her card. 'S-y-l-,' she'd practice."

"You mean, like the name on the light bulb back then—Sylvania?"

"Yes."

My stomach felt like it was at the top of a roller coaster ready to plunge. I was surprised at my fear.

"He raped her...all through grade school...he raped her...different ways. He made her do things. He told her she had to be silent. She had to be silent or else." Diana stopped and waited.

I couldn't speak.

"What?" Diana asked. It was a familiar what and gave me the feeling that she was lowering her head to look into my eyes.

"What?" she asked. "What's wrong?"

"Diana, it's just so...so...horrific. I'm shocked. I'm sad."

On the other end, I could hear a sigh, not of resignation, not of shared sorrow, but of relief. I could imagine her slinking back into a metal chair, relieved that that was all. I could almost see the shrug of her shoulders as I heard the words from a voice that was raspy and low with a sarcastic edge of inflection.

"Why are you sad? Don't be sad. So what? So nothing. That's life. Don't look at it and it will go away."

If one word would have been different, just one word; if her tone didn't match the tone I saw hours before, I might not have guessed. If the story were less horrific, I might not have known. If she hadn't said "gave me the finger spelling card;" if her name hadn't started with "S-y-l" like the old Sylvania light bulbs. But in this conversation, I knew. And from Diana's silence on the other end of the line, I knew she knew that I knew. My knees were shaking from fear I couldn't explain...that strange kind of fear that arises when you don't know if you could be in danger.

Now everything made sense...paradoxical, unbelievable sense. I felt a surgical matter-of-fact-ness as I spoke now.

"Diana." I dared to hear the answer I thought I knew. "Diana, why does Sylvia have to get to 55th Street?"

Her voice held an unspoken Duh! "That's where our psychiatrist is. Sylvia needs to learn how to take the bus. Dr. Holland has never met her. She needs to meet Sylvia."

"What do I need to do?" I asked.

I could imagine Diana's eyes rolling as she raised her voice.

"She needs to learn how to take the bus!"

I held my chest to stop my racing heart and whispered, "I understand."

We both stayed silent. Finally, I swallowed hard and said, "I can do that." I didn't know how, but I knew I had to. With hands still shaking, I hung up the phone.