Resources

From Category:

Terrain

Founded in 1997, Terrain is an online journal of creative writing and artwork with a sense of place and an ecological consciousness. They accept poetry, essays, fiction, articles, artwork, videos, and hybrid-genre work. Regular submissions are open from early September through April 30, and contest submissions from January 1 through Labor Day. Their ongoing series of "Unsprawl" case studies features locales that embody sustainable urban design. Contributors have included Rick Bass, Wendell Berry, Hannah Fries, Naila Moreira, and Pattiann Rogers.

Terrible Minds

Fiction writer and "freelance penmonkey" Chuck Wendig delivers ballsy, bracing advice for writers at his entertaining and useful blog. Got writer's block? He'll tell your inner demons where to go and how to get there.

Tertulia

Tertulia is a no-frills website builder for authors who don't want to tinker with complex software programs. They have a library of website templates designed to showcase books, and an email capture tool that integrates with popular newsletter programs like Mailchimp. Pricing is under $10/month.

Text Etc

Formerly Poetry Magic: A large collection of articles on writing poetry, understanding poetry and getting published. Novice and advanced topics covered. Examples include modernist poetry, postmodernist poetry, sounds in poetry, performing your poem and chaos approaches to poetry analysis.

Text Power Telling

Text Power Telling is a nonprofit literary organization that provides opportunities for survivors of sexual trauma to heal through creative writing. They publish an online literary journal and sponsor writing workshops online and in Bergen County, NJ.

Textbook Illustrations of the Human Body

This poet's voice is eminently likeable, humble and wise. Whether he is finding spiritual wonder in nature's complexity, or working his way to reconciliation with aging parents, Estreich's gift for elegant and original phrases never seems like showing off. This book won the 2003 Rhea & Seymour Gorsline Poetry Competition from Cloudbank Books.

Thanks

By Kaecey McCormick

We sit on the cool rocks and watch the stars swing past the moon

kicking up the dirt, dropping pixelated tears as they go.

It's seeing this with you against the silhouette of our grief:

the burned dreams, the small mounds of dirt under too-large stones,

our fingers reaching for each other's in the dark.

Their laughter breaks through the glass of our memories,

turns our shroud to dust, tugs at our lips and pulls up the corners.

It dries our eyes with handkerchiefs sewn from patchwork dresses

dyed in kindergarten colors and the mood shifts, floats us toward the harvest moon—

raises our eyes from the dead.

I'm watching you smile as you watch their joy and a quiet thrill grabs

my throat because I know what we have though not enough is enough.

And my fingers

as they stroke the soft flesh on the inside of your arm

whisper thanks.

That Great Baseball Summer of 1982

"Break the Guinness record?"

"Who, YOU? You must be KIDDING!"

The cries of laughter

that rang through the hills of Willapa Town

that summer when the mill was down

and the woods were quiet too,

were cries of disbelief, mostly,

that any fool who sat on a stool

at the local pub could hope to rub

elbows with a Guinness award for endurance!

But the echo resounded with glee!

Almost like a guarantee

that more spirited young lads had not yet been born!

"Then we'll make it a BENEFIT game!

And YOU can have the fame!

For we KNOW what we're made of!!"

cried the boys of a feather whose days together

were previously spent

walking the tightrope in work and in play,

flirting with danger 'most every day,

(or boozing and cruising and closer to losing

sight of more tomorrows

than any day on record anyway).

So, a benefit marathon was born

in Willapa Town when the mill was down,

in that great baseball summer of 1982,

and the cries that rang through the evergreen hills

changed in tune to ones that sang

"They AREN'T kidding!" once the 300th inning began!

***

The stands were full now,

applauding the boys in the field,

and so were the skies which poured forth

their own sentiments to nourish the crops in the field,

but which did little for the boys in the field

except to build some character

by presenting yet another challenge called MUD!

Then, while the innings were changing,

and the days were turning to nights,

so too the hecklers changed,

now becoming care takers

of sprains and strains and blistered feet,

of socks, and towels, and things to eat,

while slow pitch ball became slow death for all

who couldn't sleep or cope or eat,

and who had no sight of tomorrow at all,

but were still hanging on

by the fragile threads of determination.

By the 4th day,

after 91 hours and 21 minutes

playing 552 innings of baseball,

with a final score of 365 to 283,

the wild-eyed crowd was cheering,

for the end was finally nearing,

and Willapa Town had HEROES!

(But was also fearing for their lives,

for when the umpire hollered "GAME!"

they watched the spent and the lame

fall in a heap, determined to sleep forever.)

***

Soon the cries that rang down

the evergreen hills of Willapa Town

were cries of pride that came from inside

for everyone loves a hero,

especially one who tried

to break a world's record

for the longest slow pitch game in history,

and raised $20,000 doing it!

"We BROKE the Guinness record

for the longest game—NO KIDDING!"

was the song they were singing then,

in that great baseball summer of 1982

when the mill was down, and the woods were quiet too,

and the heavens poured nourishment

on the crops in the field,

and lessons in character building

were handed down to the next generation

of spirited young lads

who would set their own records

for hanging tough

by the fragile threads of youth,

while still hoping for a glimpse

of yet another tomorrow.

Copyright 2011 by Isa "Kitty" Mady

Critique by Tracy Koretsky

It's spring at last. What a perfect time for a poem about baseball! And what better way to convey the fun and drama of that game than with one of poetry's most enduring and entertaining forms: the ballad.

It's also a great opportunity to remind readers that WinningWriters.com has an exciting new Sports Poetry and Prose Contest. So, this month, with the help of "That Great Baseball Summer of 1982" by Isa "Kitty" Mady as well as a few classics, we'll look at how vibrant sports writing is constructed.

In general, I am not a fan of the common practice in which a teacher tells a student to go off and study a famous piece. This can intimidate, squelching the creative urge with the weight of the comparison, but there is a reason teachers do this. Sometimes it is the best advice.

In this case, it serves, amongst other things, to demonstrate how perfectly Mady has married topic to form. Today the word "ballad" has come to mean a slow popular song, usually romantic. Originally, though, ballads were the fare of wandering minstrels. Literally singing for their supper, balladeers had to engross if they wanted to eat. Other than light verse, which delights with wit, there is no other poetic form intended solely to entertain. The ballad, however, does not operate by wit. Rather, its vehicle is plot.

As a plot-driven form, ballads frequently laud a single character, often a tragic hero, as in "Barbara Allen", which dates as least as far back as the 17th century, yet endures to this day as one of the most popular folk ballads in the British Isles. Notice that, just as in Mady's poem, dialogue plays a significant role. In fact, ballads are more likely to contain dialogue than any other form of poetry. At its best, this dialogue conveys regional color through accent or idiom.

Also like Mady's piece, there is a rhyme scheme. "Barbara Allen" is an example of the traditional ballad scheme of a/b/c/b, though forms vary and evolve over time.

At first glance, you might not think Mady's poem suits that description, but a little deeper analysis shows that, setting the given line breaks aside, a pattern emerges for much of the first long stanza:

The cries of laughter that rang through

the hills of Willapa Town

that summer when the mill was down

and the woods were quiet too,

were cries of

disbelief, mostly, that any fool

who sat on a stool

at the local pub could hope to rub

However, the a/b/b/a; c/d/d/c scheme soon unravels. If Mady should choose to maintain it, she will need to rework the next few lines. Line thirteen might end with "chance", for example, to form a rhyme with "endurance". Alternatively, the somewhat awkward syntax of line 10 might reconfigure to something like "winner of a Guinness" or "Guinness award", both of which offer other opportunities for rhyme.

As an example of the kind of redrafting I mean, here are a few revised lines from the end of the first stanza:

So, in that great baseball summer of '82

a benefit was born—a marathon

in Willapa town, when the mill was down

and the cries that rang through

A note here about using numbers in poems: as poetry is an oral form, numeric words must indicate how they are to be said aloud. Is $20,000 meant to be voiced as "twenty thousand dollars?" If so, write it that way. Other choices might be "twenty g" or "grand" or "thou," all of which are more colorful, fewer syllables, and offer more possibility for rhyme. Likewise, when dealing with time, one might choose "21 minutes past 91 hours," for more rhyming opportunities, or "nineteen hundred and eighty-two" to affect a folkloric tone. Many creative choices are possible.

In the second section Mady foregoes rhyme for repetition: "field" pairs with "field"; "changing" with "change"; "eat" with "eat". This is a wonderful impulse. As a second canto, it operates like the second movement in a symphony. A new timbre and tempo refreshes the reader. Also, as its subject is the numbing iteration of innings, the repetition provides a sonic counterpart. The problem is, just as in stanza one, the pattern peters out.

We might question here whether it is worth the bother to adhere to a pattern and break lines to emphasize it. In very practical terms, rebuilding a poem towards a specific scheme is difficult and, because rhyme is so noticeable, it can easily overwhelm. Today, most traditional forms have been revisited, favoring subtler rhymes.

Personally, I enjoy that Mady has embedded many of her rhymes internally. They are less predictable, keeping the poem fun to read. More importantly, their frequency and exactness create a kind of drumbeat, heightening the drama. For that reason, the scheme, whether presented internally or as end rhyme, is well worth a formal analysis that will continue and strengthen it.

Besides, with a completed scheme, "That Great Baseball Summer of 1982" would suit formal poem competitions in which, I believe, it might do well. Also, in Mady's particular case, I sense such a revision is more attainable than usual. For one thing, the scheme is already nearly intact. More importantly though, I feel there is still work to do on a more basic level that will present new possibilities. Specifically, I refer to diction.

Have a look at Franklin Pierce Adams's "A Ballad of Baseball Burdens". The first thing you might notice about it is that it is not, in fact, a ballad—a story, but rather an ode—a praise song. Adams, famous in his day for his light, witty, verse, has indulged in a bit of consonance at the expense of accuracy. Never mind. Notice instead his lively diction choices. Verbs like "swat", "biff", "clout", and "slug" are the spice that makes good sports writing tasty. Expressions from the lexicon like "jasper league" and "on the knob", not to mention the various players' names, add authenticity, perfectly setting the tone.

Now, Ms. Mady has already demonstrated that she is a natural rhymer. Redrafting with striking, active verbs, and phrases from the baseball diction family will not only give her lots of room to formalize her rhyme scheme, they will make this already fun poem an absolute pleasure to read.

That is, once she reorganizes her story a bit. Remember, first and foremost, the ballad is plot-driven; its intent, to relay a dramatic tale. As a case in point, let us refer to Ernest Lawrence Thayer's ever-popular "Casey at the Bat". (By the way, would-be sports writers, check out the great links on the left of that page. Also, there is also an awfully fun reading of the poem by James Earl Jones.)

Now "Casey at the Bat" is a masterwork, a true piece of the American canon, beloved by generations. I apologize again for comparing Mady's poem to it, but there is so much there to be enjoyed—and learned from.

Once again we have lively diction: "the former was a hoodoo and the latter was a cake." Dialogue like "We'd put up even money now" is idiomatic, contributing to the tone, a tone consistently humorous in its self-consciously heightened drama: "ten thousand eyes" vs. "five thousand tongues." I particularly admire the rare expressive use of meter in the phrase, "and a smile on Casey's face," which breaks the rhythm for a quick triplet, like a child's sudden happy skip.

But above all, what makes "Casey" succeed as a dramatic work is that it has beats. "Beats" are what fiction writers and playwrights call the movement between characters, or between character and setting—the back and forth. See how Thayer has used the movement back and forth between the playing field and the crowd to develop the crowd as if it had a singular personality?

Baseball, as a subject, lends itself naturally to beats, with pauses inherent in its nine innings, and one, two, three strikes, you're out. Take a moment to think about how the beats work in "Casey". See how they are present in every stage of the plot: the set up, the main action and the resolution?

Take note too, of where Thayer chooses to begin his story. There is some brief set-up to the action, but we are already in the game. "That Great Baseball Summer of 1982" uses a different strategy—a long preamble. It's a good choice, imbuing a quasi-folkloric tone. But what I question is whether the first lines are the place to reveal that this ballgame will be played in the hopes of a Guinness record. It might work better coming later, as a surprise. And I'm pretty sure there may be a few beats missing before that 300th inning.

The second section of Mady's poem is more directly comparable to the action in "Casey". The game is in progress. We are told (alas, not shown) that rain becomes mud. In the next beat we discover that the hecklers change. But we never knew there were hecklers in the first place—a sign that we are missing a beat.

The beats in the second section of "That Great Baseball Summer..." might possibly go something like this:

1) The hecklers begin.

2) Day turns to night.

3) The sky threatens rain.

4) The players react.

5) The crowd reacts.

6) It does rain! Boy, does it rain!

7) More hours, more minutes, more innings...

8) Could they break the record? (What record? An exciting new element!)

9) The crowd become caretakers.

And so forth. Mady is clearly a spirited storyteller. Once she takes the time to list and order all the details of her drama, I suspect the words will offer themselves.

You may be wondering where there is room in this already long piece for added beats. Actually, the poem is not overly long for a ballad at this point, though much longer and, indeed, it might strain the reader's attention. Removing some of the redundancy will open space for character development and specific detail.

Make sure every detail is actual information and new information at that. If it refers to previous information, it must develop it. Currently, the poem's third section is mostly recap. Mady has used repetition here as a type of coda. While this is a solid musical instinct, remember, codas generally modulate in key. Bear in mind too, that other great ballads like "Casey" and "Barbara Allen" resolve almost immediately after the final action, allowing their dramatic finales to linger in their impact.

And yes, I said "other great ballads". I really believe that, with revision, the addition of some entertaining and memorable details, Mady has everything she needs to craft an excellent poem. She has a charming story to tell and, apparently, an innate musicality with which to tell it. I only hope that when her skies pour "forth their own sentiments", she'll slip in a little reference to Mudville, and that, for a moment, there will be joy.

Where might a poem like "That Great Baseball Summer of 1982" be submitted? The following contests may be of interest:

Alabama State Poetry Society Poetry Competition

Postmark Deadline: March 23

Prizes up to $50 in a variety of themed categories; previously published poems accepted

Writers' Workshop Annual Poetry Contest

Postmark Deadline: March 30

Top prize in this contest from the Writers' Workshop of Asheville, NC is your choice of a 3-night stay at their Mountain Muse B&B, or 3 free workshops, or 100 pages line-edited and revised by their editorial staff

Kay Snow Writing Awards

Postmark Deadline: April 23

Oregon's largest writers' association gives awards up to $300 in adult category, $50 in student category, for poetry, fiction, nonfiction, screenwriting, and juvenile (a short story or article for young readers)

Senior Poets Laureate Competition

Postmark Deadline: June 30

Amy Kitchener's Angels Without Wings Foundation awards top prize of $500 for poems by US citizens (including those living abroad) who are aged 50+

This poem and critique appeared in the March 2012 issue of Winning Writers Newsletter (subscribe free).

The 1619 Project at the New York Times

In 1619, the first ship of African slaves arrived at a port in the British colony of Virginia. This series of feature articles from the New York Times Magazine surveys the far-reaching legacy of black people's enslavement. These pieces aim to show how America's unique economic and political dominance was built on the wealth extracted from slaves and the racism that underpins our social structures. The full text has been made available for free on the website of the Pulitzer Center.

The 19th Wife

By David Ebershoff. This multi-layered novel intertwines the story of Brigham Young's ex-wife Ann Eliza, a real historical figure who successfully campaigned to outlaw plural marriage in the United States, with a modern-day murder mystery in a polygamist Mormon splinter group. The narrative unfolds through fictional documents—correspondence, research papers, autobiographies—suggesting that truth is subjective and many-sided.

The 3 A.M. Epiphany: Uncommon Writing Exercises That Transform Your Fiction

Over 200 inventive exercises to help you break out of old patterns and discover new things about your characters. Kiteley uses word limits rather than time limits to provide discipline and focus. The prompts are grouped according to the technique they are designed to develop (timing, narrative voice, and so forth) and include brief discussions of why they work.

The 300-Word Gateway: How Going Short Can Fast-Track Your Lit Mag Success

In this 2025 guest post on Becky Tuch's Lit Mag News Substack, Darien Gee recommends writing micro stories and essays for both craft and career reasons. Short forms compel you to make every word count, which can help you identify key moments in a longer manuscript and eliminate filler. A portfolio of short pieces gives you many options for submitting to literary journals while you also pursue longer projects.

The Academy of American Poets

Site includes over 1,200 poems by 450 noteworthy poets, with an emphasis on American and 20th century poets. Search by poem, poet and text. Numerous audio selections. See also the Online Poetry Classroom sponsored by the Academy, with its suggested 100 Best Poems to Memorize.

The ADD Writer

In this 2020 blog post, author and writing teacher Michael Jackman shares tips for writing productively with attention deficit disorder. If daily routines and schedules don't suit the way your brain is wired, try some of his strategies for jump-starting your creative enthusiasm, such as exercise, travel, and enjoying cultural events. Above all, take the long view of your productivity and don't measure yourself against people with different needs.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

This Pulitzer-winning epic novel about the golden age of comic book superheroes is also a love song to New York City Jewish culture in the years surrounding World War II. Two boys, a visionary artist who escaped Nazi-occupied Prague and his fast-talking, closeted cousin from Brooklyn, lead the fantasy fight against Hitler by creating the Escapist, a superhero who is a cross between Harry Houdini and the Golem of Jewish legend. However, their real-world dilemmas prove resistant to magical solutions, and can only be resolved through humility, maturity, and love.

The American Aesthetic

Launched in 2014, The American Aesthetic is a quarterly online journal searching for poetry that conveys in its composition—as well as in the sound, cadence, and possibly even musicality of its words—an expression of honesty and purpose that somehow rings true. See website for free sonnet competition with small prizes.

The Art of Invisible Movement

Maggie Stiefvater is the New York Times bestselling author of the Raven Cycle series and other award-winning fantasy and magical realist novels. In this blog post, she advises fiction writers to make the same scene accomplish more than one task. For instance, a quiet, transitional scene does not have to be filler; it should reveal something important about backstory, character, or atmosphere. The key to good pacing is to use a variety of scene structures: earn those quiet moments by interspersing them with higher-energy action.

The Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP)

AWP's bimonthly magazine, The Writer's Chronicle, is well worth a subscription, and includes information on grants, awards and publishing opportunities. AWP members may access a special Job List of academic and non-academic jobs. Search AWP's extensive program directory for a writing program near you, and consider attending AWP's popular annual conference, a good value for its seminars, networking and readings.

The Audacity of Prose

In this 2015 essay in the online journal The Millions, Nigerian novelist Chigozie Obioma critiques the fad of literary minimalism, arguing that the glory and purpose of literature is to "magnify the ordinary" through language that rises above everyday banal usage. Obioma's debut novel The Fishermen was published in 2015 by Little, Brown.

The Autism Parent Memoir I’d Love to Read

Are you writing a memoir about raising a child with autism? Consider autistic readers' perspectives to avoid stereotypes. Be curious about other ways of processing information, and strengthen your literary craft with introspection about how your own mind works.

Annie Mydla, Managing Editor

Note: In this article, I mention things that "autistic people do" and experience. This can only ever be a figure of speech, because autistic people are so different from each other. As the saying goes, "If you've met one autistic person, you've met one autistic person."

As an early-round judge in the North Street Book Prize, I see several parent memoirs (or APMs) per year by non-autistic parents raising an autistic child or children, often with common comorbidities like learning disabilities. My autistic profile outwardly differs from the children these memoirs tend to be about—I'm hyperverbal and lack a learning disability. But we share a lot of underlying difficulties in common:

Sensory processing issues

Interoception, receiving and interpreting physical cues from inside the body. The problem can be receiving too much or too little. I receive too much.

Proprioception, the sense of where the body is in space. I receive too much information.

Difficulty interpreting and acting on social cues in real time

A bottom-up processing style

Intense interests in some areas and none at all in many common ones

Monotropism, the tendency to deeply engage with only one thing at a time, leading to challenges with switching tasks and tasks with multiple steps.

Holotropism, having "wide open sensory gates". Body, mind, surroundings, and other people seem more like one thing than separate things.

I tend to identify with these kids a lot.

For this reason, I read autism stories very, very carefully. I'm looking for The One. The APM that inspires me and makes me happy. And you know what? I've been looking for a while.

Maybe if I write a blog post about it, my dream APM will come to me. So here's a list of the top 7 things I'd like to see in an Autism Parent Memoir.

1. The memoirist knows what they don't know

A big dream of mine is to read an APM where the non-autistic narrator fully recognizes they have no idea what it's like to be autistic. Such an APM could start with a look at the double empathy problem and how it works in the life of a non-autistic parent of an autistic child.

Often, autistic people are described as "not having empathy". But the double empathy problem posits that while autistic people do not always automatically understand where non-autistic people are coming from, the problem is just as great with the non-autistic in not automatically understanding where we are coming from.

Here's a practical demonstration of how the double empathy problem can come into play in an APM. I encountered a memoir in which a mom was frustrated that her child "continued to test his boundaries" by going on "unsanctioned explorations" into other rooms, the yard, or any other place his parents didn't wish him to be at the moment. The parents were continually creating barriers with furniture, brooms, and other household objects, which the child would dismantle before leaving the room. This happened frequently despite all the times the parents explained the rules and punished him for breaking them.

To the narrator, the child was obviously "testing his boundaries". There were no other interpretations offered. But the phrase "testing boundaries" shows assumptions. It implies that a) the child is intentionally breaking the boundaries the parent has set up and b) the child knows he is disobeying the parents.

But is "intentional disobedience" the only interpretation? I don't think so. An autistic reader could think of a number of autism-related motivations for the child's behavior. He might be...

Seeking to escape overstimulation in the household or environment

Seeking solitude (often comfortable for autistic people, to varying degrees depending on the person)

Honoring internal demand avoidance. This is different from disobedience because it is not based on the child's desire to thwart the parent's authority. Demand avoidance is an internal need that occurs with no regard to the nature of the demand itself or who/what is making it.

Another possibility is what I think of as "circuit joy". Some autistic children and adults take pleasure in loops and circuits. Given the fact that the parents keep creating barriers out of household items, the child's behavior could be interpreted as showing evidence of pursuing a complete circuit. The parents create a puzzle with their interesting barrier, the child solves the puzzle, and then the parents have their familiar reaction (in this case yelling, scolding, begging, punishing). For an autistic child enjoying the circuit, the reaction of the parents is part of the reward of completion, even when the parents think that their reaction ought to be interpreted by the child as a deterrent.

Am I insisting that any of these motivations were the actual cause of the child's behavior in that memoir? No. And am I saying that as an autistic person, I would know the child better than his parents do? Again, no. But the fact is that there are many motivations which to an autistic person may be very pressing and/or rewarding, but of which a non-autistic parent might be unaware. It would be wonderful to read an APM that resists projecting assumptions on autistic children's behavior in situations where there are other possibilities.

2. The memoirist relates their understanding of their child's inner experience to their own lives

Something I have never seen in an APM, but would seriously love to, is a plotline in which the parent strives to relate to the child on their own terms. Eventually, the parent becomes able to see their own self-identified non-autistic lives through autistic lenses. This happens quite a bit in real life, sometimes to the point where a parent seeks autism screening for themselves. But I've yet to encounter it in an APM.

In that ideal memoir, we might see the parent asking themselves questions like:

My autistic child has sensory needs. But what are my sensory needs as an adult, self-identified non-autistic person? How do light, sound, movement, texture, temperature, and more impact my mood? My ability to focus, switch tasks, complete steps?

Answering questions like this, the parent may realize that they can't stand the breeze generated by their ceiling fan, they dislike working in their office while the neighbor is mowing the lawn, or they become unduly irritated when other drivers leave their high beams on at night. I could imagine an APM in which the parent avoids these sources of aggravation or changes their reaction to them, in the meantime learning how to help their autistic child to avoid their own sensory stressors. It also becomes easier for the parent to write their memoir due to the lack of sensory irritation—and to weave tension and relief through their narrative by using sensory triggers in some scenes.

How are my interoception and proprioception? How do they impact my experience of the world and of myself? Are they making my experience different from other people's, or different than what I'd have liked?

Perhaps the narrator thinks back to gym class in middle school and how they were embarrassed by never being able to catch the ball, or how they still sometimes put both feet into one pant leg even when they are paying attention (proprioceptive issues). Or if they get sick, they can't tell right away, so they always end up leaving work in the middle of the day rather than staying home to begin with (an interoceptive issue). These realizations help them empathize with some of the things their own child has trouble with and also leads them to forgive themselves for their "non-optimal" behavior. The end-of-day headache they've been attributing to working too much on their memoir, they now realize, is actually due to hunger. Their hypo-ability in that interoceptive arena makes them forget to eat. They start using a snack timer while writing and end the day in a much better mood.

What is my level of verbal processing and production on any given day? When I am tired, stressed, or overwhelmed, versus when I am relaxed?

I picture an arc in which the parent often yells at their children in the mornings before school. However, due to learning more about autism, they realize that their own verbal processing needs extra time to "wake up" in the morning. The parent then realizes that they were becoming upset by the noise and demand to respond in the morning—and that starting to yell at everyone was making it worse. Steps could be taken to make the morning routine calmer and quieter for everyone's benefit—especially the autistic child, who also needs a verbal warmup time each day. Later, the parent found that the quiet time in the morning made it easier to transition into whatever they were doing next, like doing their job or working on their memoir.

Do I have a bottom-up processing style, where I see details first and then the big picture, or a top-down processing style, where I see the big picture first and then zoom in on details?

Maybe the parent has always had clashes with their parents, teachers, co-workers, and bosses due to asking too many "nit-picky" questions. The parent learns that they have a bottom-up processing style thanks to researching their child's autism and is more aware of why they need so much information before starting a project. They become more strategic in how they ask questions and also use a broader range of resources to get the answers they need. This experience helps them to replace irritation at their child's probing questions with a sense of the child's desire to please them by really getting things right. The parent also identifies that their detail-loving disposition has been slowing down their memoir-writing process, though it has been a significant strength in writing immersive scenes.

What is my executive functioning like day to day? Do I ever have trouble making or keeping plans, focusing on a single task, or completing tasks? Do I procrastinate (either naturally or to avoid coming up against other executive functioning problems)?

A parent who has always deplored their own inability to concentrate learns about monotropism, and through that, polytropism—the need for a wider variety of topics and tasks in order to maintain their mood and productivity. The parent can then forgive themselves and focus on arranging their lifestyle to fit their needs. It also strengthens a sense of solidarity with their child. They both struggle with executive functioning—just from different ends. And now the parent can reconsider whether they really need to be so down on themselves for having a stop-and-start pattern in writing their memoir.

Do I ever experience black-and-white thinking, difficulties putting information and priorities into a hierarchy, or demand avoidance?

Autism parents often have to deal with stigma and ignorance in other people's reactions to autism. The parent in question has had some negative interactions with fellow parents, leading them to reject the social scene in their neighborhood. But now the parent has learned about black-and-white thinking—the knee-jerk reaction that something is all one way or all another. That leads them to reflect that the neighborhood parents have had a range of reactions, not all of them bad. The parent is now more equipped to interact with the neighbors on a case-by-case basis and be more aware of black-and-white thinking traps in the future, including with their own child and in the process of writing their memoir.

Is changing plans uncomfortable for me? Do I need a certain amount of time to process plan changes? Is my experience different depending on whether it is me changing the plan, or I am subjected to someone else's change of plan?

Let's say the author's family moved to a new house six months ago. The parent hasn't worked on the memoir a single time since, even though everything has been unpacked for at least three months. In the past the parent would have scolded themselves for being lazy. But learning more about the child's autism has given them the awareness that their own brains can take time and bandwidth to process change. A month or so later, they've processed the change and are working on their memoir again.

The questions above, and many others related to autism, affect every human to various degrees. But for autistic people, they and others define our lives, shape our experiences, and inform our priorities, personalities and actions. I'd love to read an APM that has the protagonist transforming their own vision of how their brain works based on what they learn about autistic people's inner experiences.

3. The narrator takes responsibility for the situations they put their child into and what happens next

Memoirs need empathy for their subjects. They need to show curiosity. A memoir is not just a record—it is an exploration. The memoirist takes responsibility for their own point of view and questions it, looking at it from a variety of angles. If the parent-memoirist isn't doing that, then the APM is not a memoir. It is an exercise in venting, self-justification, and editorializing. And no memoir is going to win the North Street Book Prize like that, autism or no autism!

The APMs we receive could do more to zero in on that explorative element, deeply reflecting on what happened and the author's part in it.

For example, I read an APM once in which the parent takes their child to the zoo. Soon, the child begins to chew on their fingers and refuses to budge from the middle of a crowded walkway. The parent tries to get them to stop chewing on their fingers and move along. The child is unwilling and starts to cry. The parent insists, lowers the child's hand away from their mouth, and tries to gently lead them off the path. The child breaks down. People stare and the parent feels judged. The narrator's conclusion to the episode expressed that: My child is such a riddle. Autism makes them act erratically. Fortunately, I'm a patient and caring person.

They may well be a patient and caring person in general. But that doesn't change the fact that they've brought their child to a loud, bright, movement-filled place without any form of protection (ear protection, sunglasses). The environment may be new for the child, which is another hardship for those of us with difficulties with change and hyperawareness of spatiality. These factors inevitably lead to the agony of overwhelm, which we observe in how the child reacts.

I see scenes like this in APMs all the time and always have trouble accepting how the narrator makes the child responsible for what happened, rather than rethinking their own actions: bringing the child to an overwhelming spot without giving them sensory protection or other accommodations. The child has been set up not just for failure, but for physical and mental pain and humiliation. Ultimately, such episodes are stories of a power struggle between the parent and the child, in which the child always loses.

It would be wonderful to see an APM from a parent who was fully aware of these dynamics and took personal responsibility for the situations they put their child into, and what happened next—treating the memoir as an opportunity to investigate rather than simply to vent or editorialize.

4. The memoirist acknowledges the parent-child power imbalance and is careful not to abuse it in their book

Speaking of power dynamics, I would treasure the chance to read an APM in which the memoirist shows awareness of the power imbalance in the parent-child relationship—especially while writing the memoir. As described above, the parent has power over the child's physical experiences. But the parent also has control as a writer, deciding:

How to describe the child inside and out ("Good"? "Bad"? "Sick"? "Inspiring"?)

How to characterize autism (A "battle"? A "superpower"? A lifelong neurobiological condition?)

How to interpret the situations in the book ("My child behaved badly at the zoo" versus "I put my child in a challenging situation, and it was too much")

I'd be so glad to read an APM that examines the author-to-subject power imbalance alongside that of the parent and child.

5. The memoirist demonstrates awareness that actual autistic people might read their book

APMs are often a way for the memoirist to vent and connect with other autism parents. That's wonderful—parents of autistic children need and deserve validation and solidarity.

On the other hand, writing exclusively for other non-autistic parents of autistic children can lead memoirists to write as though no autistic person will ever read their book. As a result of this, the content and language can become exploitative and dehumanizing without the non-autistic writer even realizing what's going on. Autistic readers, though, will pick up on these things immediately.

When I say "exploitative," I mean material that puts the child's most vulnerable moments in the world for all to see. Some exploitative scenes I've read in APMs include depicting the child:

Having a meltdown in a public place

Opening their own diaper and throwing feces around the living room

Fighting (verbally or physically) with teachers, doctors, or other authority figures

Wetting the bed longer into their childhood than their peers

Banging their head on a table or wall

Non-autistic autism parents may relate to these scenes, but is it worth it? The child's privacy has been violated, and any autistic reader who comes across the book will be horrified. Does any child deserve to have these private moments of vulnerability, fear, pain, and overstimulation exposed on Amazon? And what does it say about the parent's feelings about their own child that they would allow that to happen? In contrast, I'd like to read an APM that honor the child's privacy and dignity and shows the parent's solidarity with the child.

APMs that don't anticipate autistic readers can also be prone to using dehumanizing language. For example, I read a book this year where the memoirist called her son a "monster child" and compared him to "the worst situations in life." I respect the author's personal experience of raising their child. Maybe to her, it really did seem like he was a monster. But to go from that internal experience, to publishing a book that characterizes an autistic child as a monster and of autism as a monster inside, is troubling. I could tell that the book was not meant for autistic eyes.

I read too many APMs that characterize autism as something other than a neurobiological condition—for example, "monster". Other phrases put a supernatural spin on autism, calling it a "superpower" or a "curse". A classic is when autism parents are called "warriors" who "fight to rescue" the child (autism is not a war or a case of kidnapping!)

The internal experience of autism is more complex than "fighting" or being a "superhero". Nothing about autism is all one way or all the other, and every autistic person has different struggles and strengths in different parts of life. That's why, when I see this kind of language in a memoir, it's a red flag. I'd love to see an APM that dissects these terms and how they're normally used in memoirs. Meanwhile, there are good resources out there for researching how to use more supportive and understanding language that won't shut out autistic readers:

https://www.amaze.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Talking-about-autism-a-media-resource_web.pdf

https://www.autism.org.uk/contact-us/media-enquiries/how-to-talk-and-write-about-autism

Any APMs that care to critique, satirize, or subvert these labels are so much more than welcome in my life and on my bookshelf!

6. The book calls out ignorance, unfairness, and bigotry in individuals and society

I haven't given up on APMs. In fact, I've seen some good stuff. One of my favorite things to find in an APM is when the author pushes back against all the ways autistic people are misunderstood, belittled, and othered. For example, I've seen memoirs where:

The parent stands up to a therapist who kept referring to autistic children as burdens.

The narrator, a special education teacher of autistic children, corrects a child's homeroom teacher whose beliefs about autism are outdated and prejudiced.

The father of an autistic child confronts a GP who won't let his child wear light-protective headwear in the examination room.

When these episodes happen in APMs, I want to stand up and cheer. They make me feel that the parent might be on my side if I was in such a situation. Which leads me to...

7. The memoir shows solidarity with autistic people

As I look back at this long list, what it really amounts to is a desire for autism parent memoirs to show solidarity with autistic people. It would be wonderful to see narratives by parents who are going the extra mile to be not only autism parents, but autism allies.

And by autism allies, I don't just mean wearing blue on Autism Awareness Day, or having a puzzle piece pin on your hat. I mean letting autistic ways of life start to inform your way of life. Don't take it for granted that it's your right to lead, explain, define. Go our way for a while, and let it change you—and what you write in your memoir.

One personal anecdote before I close. I have a severe light sensitivity and often have to wear sunglasses inside. I'll never forget the joy I felt when, during a Zoom consultation on a crime novel, the critique client put their own sunglasses on in solidarity. I asked him, what inspired you to do that?

Turns out he was an autism parent.

The Bad Version

The Bad Version, a print and online journal, is produced by a group of recent Harvard grads, who met during their time at The Advocate and The Crimson. They publish essays, fiction, and poetry, and all of their published pieces have responses to them that comment on the piece, challenge it, and further its ideas. Editors say, "We picture The Bad Version as a snapshot of an ever-evolving conversation."

The Bare Life Review

Founded in 2017, The Bare Life Review is a literary biannual devoted entirely to work by immigrant and refugee authors. Though the impulse behind its creation was political—to support a population currently under attack—the journal's focus remains wholly artistic, publishing work on a wide variety of themes. Submissions are accepted August 15-November 30. Contributors must be foreign-born writers living in the US, or writers living abroad who hold refugee or asylum-seeker status. Translations are accepted. This is a paying market.

The Barricade

By Ned Condini

I would be glad to take his place

like a prince of orphans, to enjoy

my pinch of power in the royal hall.

But this elusive king leaves the door

ajar, warm coffee on the table,

the lights on & the book still open.

I lunge thinking there's the answer

& find a whiff of incense wafting

beyond the room into the dark where he vanished.

I know he will always be

millions of years away from me,

isolated on the remotest star;

yet the fact that he seems to move

when I, too, move makes me believe I'm on his track.

Fulfilling myself yet struggling

to get rid of the self that's me,

I am the Pompei man who saw

what was coming yet stretched out his hand to save

one piece at least of the barricade erected

against you, fighting you tooth and nail,

gripping the axe of his youth.

The Bean Trees

Written in 1988, the first novel by this now well-known author and activist is first of all a heartwarming and funny story about an unlikely "family of choice" formed by a single mother and her baby, a young woman fleeing her dead-end Southern town, and an abandoned Native American toddler. More ambitious than the typical "relationship novel", the story puts a human face on political issues like interracial adoption and the plight of South American refugees.

The Best American Short Stories 1999

A particularly fine installment of this annual series, the 1999 anthology includes a wide spectrum of styles and ethnic backgrounds, with emotionally compelling tales that leave the reader with much to ponder. Standouts include Nathan Englander's 'The Tumblers', which casts the shadow of the Holocaust over Yiddish folklore's mythical village of Chelm; Sheila Kohler's 'Africans', a quietly chilling account of a family's disintegration under apartheid; and Heidi Julavits' 'Marry the One Who Gets There First', an unlikely love story told through wedding-album outtakes.

The Best of Michael Swanwick

By Michael Swanwick. This first volume in a career retrospective of the award-winning speculative fiction author spans over 25 years of creative tales about planetary consciousness, time travel, steampunk con artists, dinosaur tourist attractions, and what would be gained and lost if we could re-engineer the human brain.

The Big Book of Exit Strategies

By Jamaal May. The award-winning poet's second collection from Alice James Books explores bereavement, masculinity, risk, tenderness, gun violence, and the unacknowledged vitality of his beloved Detroit, in verse that is both muscular and musical. Nominated for the 2017 NAACP Image Awards for Outstanding Literary Work in Poetry.

The Bind

Founded by award-winning poet Rochelle Hurt, The Bind is an online journal that reviews poetry books by women and nonbinary authors. They review chapbooks, full-length collections, hybrid works, and translations. The Bind is interested in intersectional and feminist writing. Read a 2017 interview with Hurt on Trish Hopkinson's blog. Visit their website for guidelines for pitching articles and requesting reviews.

The BitterSweet Review

Launched in London in 2022, The BitterSweet Review is a publishing platform dedicated to the advancement of queer literature and visual culture. In addition to the biannual literary journal, which is published in print and online, they offer workshops and limited-edition artwork for sale.

The Block

By Sherry Ballou Hanson

I used to be an oak

before they cut me down.

I was substantial they said.

Catholic bells pealed for generations

and stars danced in my branches

all the nights of my life

as a tree in a wood

along the Thames

but things change. One day they came

and I was hauled out dead

before the sun had set;

better to have silvered among the stumps

than do the devil's work.

I was paired with axe

and together we served the Tower

four hundred long years,

shrinking from the screams at Tyburn

and the mob at Tower Hill

until it was our turn.

The first was worst, a mess of blood,

the severed head cut loose;

we scarce could stand the shame.

When Lady Jane knelt at last,

I felt my death again, wondered

how axe and I came to this fate,

but one goes on.

When the Earl of Essex

finally bowed his head,

we prayed for a sharpened blade.

Seven times we stood to the duty.

Axe kept his shine and I my gloss

but we were hollowed out.

Scrubbed clean now we are shunned

by all except the rack and manacles.

Nights in the Tower are cold,

and life was beautiful as a tree.

This poem was published in her collection A Cab to Stonehenge (Just Write Books, 2006) and was part of the portfolio that won the 2014 Paumanok Poetry Award.

The Blue Mountain Review

Published by the Southern Collective, the Blue Mountain Review is a quarterly journal of arts and culture. They publish interviews with writers, lit mag editors, artists, and musicians, plus original poetry, fiction, and essays. See their website for the current theme for their annual poetry chapbook contest.

The Blues

By Joan Gelfand

"I think there's something in the pain of the blues, something deep, that touches something ancient in Jewish DNA." —Marshall Chess, founder of Chess Records, producer of Chicago blues.

It was news to me that Jews took up the chore of indigo

Dyeing. It was messy, a job in which no noble

Deigned to engage. Fingers, forearms, clothes,

Stained from steaming vats.

"The stench," they complained.

And, holding their noses they

Created a tone so rarified women fought for the right to buy.

A logical progression, this blue

Manufactured by Jews who, as you knew,

Never felt at home—and still don't.

This blue, encoded in the bones, was royal, leaped centuries to David's harp

His poems of yearning for God and Jonathan's forbidden love.

These blues wept and bled, crept along diaspora routes

All the way to Dylan. Today, we mourn Pittsburgh Jews.

The same hands that mixed indigo, lent a hand to suffering wanderers, immigrants,

The displaced, murdered. They recalled their own treacherous crossings.

The blues. The Shoah. Dachau, Pittsburgh.

Indigo, David, bloodlines. Lines of blood

And still, an outstretched arm, an open hand.

The Bombay Literary Magazine

Published three times a year, The Bombay Literary Magazine is an online journal based in India, accepting unpublished fiction, poetry, translations, photo-essays, and graphic fiction in English from around the world. See their submissions page for their next open call. Accepted authors receive 5,000 rupees, which is approximately $60, for each piece.

The Book Designer

This site, run by publishing and graphic design expert Joel Friedlander, gives resources to help self-publishing authors design professional-looking books. The site includes articles on marketing, a guide to software options, typeface suggestions, and book design templates.

The Book of Folly

The mother goddess of female confessional poets, Sexton brings back the truths that lie on the other side of madness. The sonnet sequence "Angels of the Love Affair" presents a visceral depiction of psychosis that is almost unbearably real.

The Book Rescuer

By Sue Macy, illustrated by Stacy Innerst. This inspiring picture-book biography of Aaron Lansky, founder of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, is enhanced with Chagall-inspired paintings of Jewish history. A good story in its own right, the book can also prompt educational conversations about heritage and assimilation, for children of Jewish and non-Jewish backgrounds alike.

The Book Speaks

By Subhaga Crystal Bacon

I cannot put my memories in order.

The moon just wrecks them every time.

—Marosa Di Giorgio, The History of Violets, XVIII

I am a jaw pried open,

old barber's pole red

and white striped, rough tools,

a little blood and pain. Then

release. Who needs Novocain?

A hit of bourbon. Quiet room.

Trees with their promise of relief: hung.

Jung said tooth loss means transition.

Beyond transitory, evolving.

I'm the place you come to unlock

what time and your mind buried

so deeply, you had to travel

the mycelium highway to reach it.

Here I find you. Innocent.

Vessel of shame and rage.

I open you. Unbutton your genes.

You are warrior. Let loose your hair.

Take up the space you crave.

Now, do you see?

You can love what you are

without flinching.

The Bookends Review

Founded in 2012 by creative writing and composition professor Jordan Blum, The Bookends Review is an online journal publishing fiction, nonfiction, poetry, author interviews, essays, book reviews, and visual/musical works from around the world.

The Boy in the Rain

By Stephanie Cowell. In this bittersweet historical novel set in Edwardian England, a young painter and an aspiring socialist politician fall in love, but their idyll is overshadowed by the criminalization of homosexuality. This book stands out for its meditative, introspective prose and its insight into how the bonds of love are tested, broken, and re-created as two people mature.

The Bride Price

Bittersweet romance set on the American frontier tells the story of a white woman and a half-Indian soldier who hope their love is strong enough to survive prejudice and the dangers of army life. The hero's seduction of a married woman is hard to square with his generally noble character, but his displays of leadership and grace under pressure are worth emulating.

The Brown Bookshelf

This book review website is designed to raise awareness of the myriad of African-American voices writing for young readers. Their flagship initiative is 28 Days Later, a month-long showcase of the best in Picture Books, Middle Grade and Young Adult novels written and illustrated by African-Americans.

The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest

We are straying from poetry here, but it's worth it. This contest asks entrants to compose the opening sentence of the worst of all possible novels. Named for Victorian novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton, originator of Snoopy's favorite opening line, 'It was a dark and stormy night.' Entry is free. The winner receives notoriety. Read the Lyttony of Grand Prize Winners.

The Business of Being a Writer

By Jane Friedman. The expert publishing blogger teaches writers about the economics of their industry in this book from the University of Chicago Press. The book is intended to help writers craft a realistic plan for earning money from their work.

The Cafe Review

Contributors have included Paul Muldoon and Taylor Mali.

The Caged Guerrilla

The Caged Guerrilla is a podcast by incarcerated writer Raheem A. Rahman about prison life, urban culture, the barriers we build for ourselves in society, and the struggle to stay free in spirit. His book of poetry and reflections by the same title is available on Amazon.

The Carcinogenic Bride

When the Big C meets the Big D, all you can do is laugh. At least, that's where poet Cindy Hochman's survival instinct takes her. Packed with more puns than a Snickers bar has peanuts, this chapbook from Thin Air Media Press brings energetic wit to bear on those modern monsters, breast cancer and divorce. To order a copy ($5.00), email Cindy at poet2680@aol.com.

The Case Against Happiness

The genially bewildered characters in this unique first collection of poetry try and fail to fit themselves into the American dream of personal satisfaction, but only because they are genuinely groping for a more substantial mode of existence that always remains just beyond the margins of thought and language. Pecqueur's wild associative leaps mirror his inability to find the coherent, contented self that the Enlightenment promised. This book won the 2005 Kinereth Gensler Award from Alice James Books.

The Center of the Universe

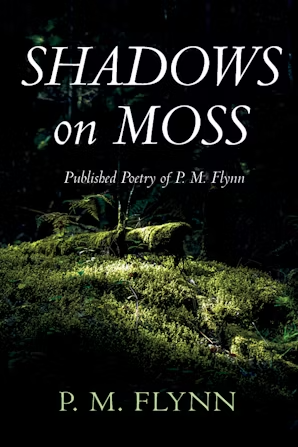

By P.M. Flynn

Behind,

thick stones are colder, deeper than time emptied,

poured into each moment that passes between clouds

that eventually disappear on the horizon.

Shadows on darkness fall from the mountains:

the sacred moving slower than geologists say,

as we turn to the bright autumn air.

(Clouds fall even in darkness.)

Under each rising sun, when there is no darkness; still—

they've always fallen. When there are shadows they fall again:

today; on the ground with less space for the sun or moon.

Before you left falling behind, before you left falling

from them, sounds always fell behind the horizon:

what is lowest behind each forest;

like trees circling the imperfect edges of me,

fallen;

touched.

There, I hear a voice before I was made, before midnight

when the universe of blue spaces between clouds of importance

closed; space you ran to seeking another new moon, or sun;

or sky with horizons closer to the center of the universe.

In seeking the center,

the blue spaces of universe first;

first:

there is no mountain,

then there is;

then there is no mountain.

(I've heard my heartbeat there.)

Then there is.

If there is darkness, you will know. If there is darkness

in the stillness between shadows falling across these mountains

I already know.

The Chapbook Review

The name of this monthly online journal is self-explanatory. In addition to reviews of new poetry and literary prose chapbooks, the site features critical essays and interviews with authors and publishers. Reviews display a lively voice and eclectic tastes.

The Character Therapist

Having trouble with your fictional characters' motivations? Wondering how to depict mental illness accurately? Jeannie Campbell, LMFT, will sit your imaginary friends down on the couch for a diagnosis.