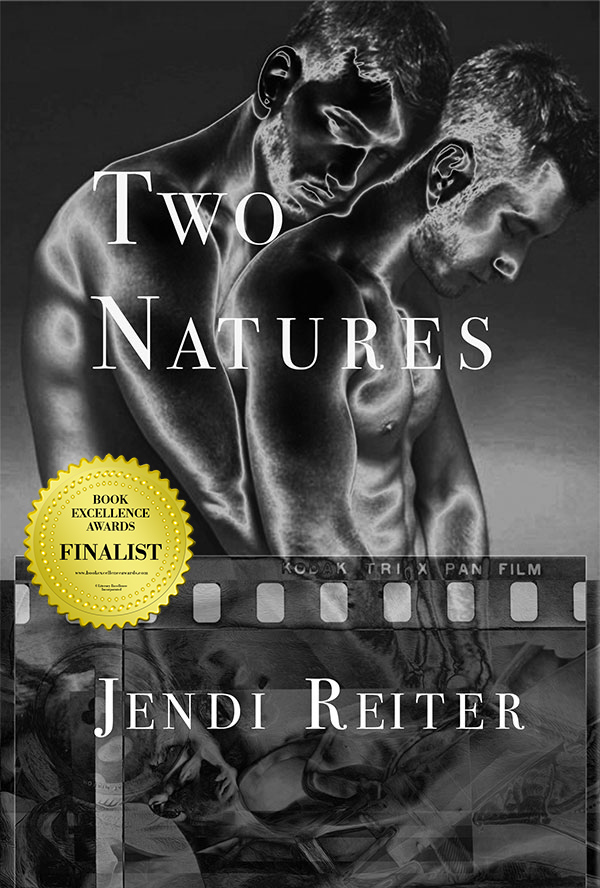

Two Natures by Jendi Reiter

- 2016 Rainbow Awards: First Prize, Best Gay Contemporary Fiction; First Runner-Up, Debut Gay Book

- Named one of QSpirit's Top LGBTQ Christian Books of 2016

- 2016 Lascaux Prize in Fiction Finalist

- 2017 National Indie Excellence Awards: Finalist, LGBTQ Fiction

Jendi Reiter's debut novel Two Natures (Saddle Road Press) offers a backstage look at the glamour and tragedy of 1990s New York City through the eyes of Julian Selkirk, an aspiring fashion photographer. Coming of age during the height of the AIDS epidemic, Julian worships beauty and romance, however fleeting, as substitutes for the religion that rejected him. His spiritual crisis is one that too many gay youth still face today.

This genre-bending novel couples the ambitious political analysis of literary fiction with the pleasures of an unconventional love story. Vivid social realism, enriched by unforgettable characters, eroticism, and wit, make Two Natures a satisfying read of the highest sort. Buy now at Amazon. View the book trailer by Zara West.

For Julian Selkirk, the dry-witted hero of this complex, wide-reaching, and unfailingly touching Bildungsroman, photography is a way of shaping the world while trying to shield himself from it. But "the boy with the camera on the sidelines of the homecoming dance" soon discovers that life and love are too sprawling, unpredictable and flawed to be contained in a viewfinder. To see what is real—we learn along with him—we must hold two natures, beauty and truth, within our vision.

— Tracy Koretsky, author of the novel Ropeless, winner of 15 awards, and Even Before My Own Name, a memoir in poems

Julian is a Southern boy and transplanted aspiring fashion photographer in New York City in the 1990s; a gay man facing the height of the AIDS epidemic and professional, social, and spiritual struggles alike as he questions himself, God's will, and Christian values in the advent of a specific kind of apocalypse.

It's rare to discover within a gay love story an equally-powerful undercurrent of political and spiritual examination. Too many gay novels focus on evolving sexuality or love and skim over underlying religious value systems; but one of the special attributes of Two Natures isn't just its focus on duality, but its intense revelations about what it means to be both Christian and gay.

— Diane Donovan, Midwest Book Review/California Bookwatch

Southern boy Julian Selkirk brings an outsider's wry and engaging sense of humor to his quest to make it in the New York City fashion world. His romp through gay men's urban culture also holds suffering, grief, pathos, and an ongoing struggle with the God of his childhood, as he comes of age during the height of the AIDS crisis. Though he gets distracted along the way—with politicians, preachers, drag queens, activists, Ironman gym buddies and sex, lots of sex—he never stops looking for real love to redeem him. An entertaining novel and a pleasure to read.

— Toby Johnson, author of Gay Spirituality and the novels Secret Matter and The Fourth Quill

We have had so many coming of age stories that it seems like that the genre has played itself out. I figured that if there would be any more written, they would have to be really spectacular. That is exactly what Jendi Reiter's Two Natures is...

The 90s were a rough time for gay men. The AIDS epidemic was devastating the gay community and the racial tensions in New York were severe. Julian is concerned with beauty and he is not relationship-oriented (or so he thought). After all, his career is based upon how people look. We would tend to think that a person like this is probably shallow but that is not the case with Julian. As he finds his way, he learns that there is much past the initial impression and short relationships do nothing for the psyche. He uses his art as a way to pay his dues to society. He remains hurt about the rejection that he received from religion and tries to make up for that by losing himself in the nightlife of New York until he realizes that this is only a substitute for his faith which he never really lost—he just subjugated it to other desires. The spiritual crisis he suffers is much like the kind that so many gay people are forced to deal with as they try to understand why they are rejected by their religions. Here the key word is "religion" and it is not as some may think, "God". There is certainly a big difference between the two...

It is a pleasure to read a novel that is literary in all of its aspects. I also found that the issue of faith that is so important to me is beautifully handled here. For those who are dealing with this issue, there is much to be learned here. We so often substitute things and events that are near for the goals that we search and one reviewer put it perfectly when he says that at that time, "Style has become God, sex has become a contact sport and jobs, money and survival are always around the corner somewhere else". We all know someone like Julian and many of us see ourselves in him. The highest praise that I can give this book is to say that "I love it" and I do. Julian is an everyman and in that he is a composite of so many gay personalities. You owe to yourselves to read this wonderful novel.

Please enjoy this excerpt from the novel:

We had decided to tell my family that Tomas was house-sitting for the violinist, who was not around to disclose what else my friend had been sitting on. One of the oldest tricks in the real-estate business is to bake cookies in a house you're trying to sell. The agent who moved a lot of Daddy's properties had once given him, as a joke, a spray-can of cookie aroma, designed for busy people to simulate the home-baked scent. As I recall, it was something like cinnamon mixed with artificial butter-flavored popcorn. If you could compress the air of family stability into a can, would it smell of roasting Cornish hens, candle smoke, stacks of yellowing sheet music, and fresh lilacs in a glass vase? I certainly hoped so.

Phil and I arrived separately, me from school, him from work. At the gym, he'd showered and changed into khaki slacks and a plaid sport coat that no self-respecting gay person would wear. Even so, it didn't disguise the splendid muscles of his back and biceps. I wanted to run my hands over the cheap wool weave. I knew his vibes too well, though, the crackling of static when he was in an untouchable mood. Fine, we would be Method actors tonight, getting into character as roommates, forgoing that last supportive kiss. We helped Tomas set the table, folding the violinist's maroon linen napkins on top of gold-edged china plates. Tomas hummed the bullfight song from "Carmen" as he tossed the salad. Ariana, who had agreed against her better judgment to be my date, arrived looking elegant in a black cardigan with metallic threads over a belted gray dress, both of her own design. She'd never be beautiful, but twenty years from now, all the beautiful people would clamor to attend her parties.

"You look like someone who could hit me up for a million bucks," I said. "What's your favorite charity?"

"You are." She winked at me and made a beeline for Phil, greeting him with atypical enthusiasm, as if to console him for the deception.

Just as Tomas was beginning to fret that the birds were drying out in the oven, my family arrived. Introductions were made all around. I hugged my sister. She was pale but more relaxed than the day before. I'd meant to seat her between Ariana and me, but when we approached the table, I found that someone (who else but Phil?) had reshuffled the place cards so that she was next to Tomas while I was stuck between Phil and Daddy.

Tomas had thrown every possible flourish into the salad, an assortment of greens with more exotic shapes than a Thierry Mugler runway show, plus baby shrimp and some pickled things that could have been Japanese radishes. Older women love Tomas; he's the guy their husbands haven't been since prom night. All he had to do was ask Mama her opinion about trends in regional cuisine and they were off like a house afire. I noticed that he promoted himself to sous-chef when describing his job. Daddy praised the white wine. He and Phil both tossed off a full glass while the rest of us were maneuvering the slippery greens onto our forks. Laura Sue quietly picked the shrimp out of her salad and tucked it under a lettuce leaf. Ariana asked my sister about her college plans. Leaning across me, Daddy and Phil started a friendly argument about whether the Mets could beat the Braves this year. My sister said she'd liked NYU better than Emory, and was hoping to become a social worker for abused children. Mama broke off a discussion of sauce-thickening methods to say that she really didn't think such heavy subjects belonged at the dinner table, dear. Ariana told a funny story about the time the bathtub fell through the ceiling in our dorm. She implied that I spent a lot of time in her room. I swallowed a shrimp tail. Daddy called Mets pitcher Dwight Gooden a faggot. Phil poured another glass of wine.

Tomas and I brought out the Cornish hens on plates sprinkled with parsley flakes. Red wine followed white. The sauce that pooled around the meat was dark red and smelled like stewed fruit. Ariana adjusted her eyeglasses on her snub nose and asked Daddy whether he'd seen our photos in Femme NY. My sister didn't know what to do with her Cornish hen. Daddy asked me why I hadn't brought the model as my date. I said she was spending the semester in Russia. Phil ate a drumstick with his hands. Mama asked about my internship with Dane Langley and whether I had met a lot of celebrities. All eyes were temporarily on me, except for Tomas who was showing my sister how to cut the bird apart neatly. Speaking too quickly, like an amateur comedian racing through his material before he forgets it, I told them about setting up a shoot for Dane and Cheryl Kingston on a windy day at Pier 17, and how my job was keeping the seagulls from flying into the lighting umbrellas. Mama said she had read an interview with Cheryl in Good Housekeeping and wasn't it a shame about her and that racecar driver. Phil made a joke about my carrying Cheryl's bags, cupping his hands at his chest. Daddy laughed. Tomas sliced Laura Sue's hen down the middle. She covered her mouth with her napkin and raced for the bathroom, but found the linen closet instead. Ariana followed her before I had the chance to stand up. Tomas' face looked like someone had thrown his favorite toy on the ground and stomped on it.

"P-M-S," I mouthed the words to him across the table, but not quietly enough to escape Daddy's notice.

"Now there's a great subject for the dinner table, right, Bitsy?" he winked. "Remember the time you lost it at the Hansons' garden party?" The tell-tale flush, the shine of alcohol, had spread over his wide round face. I nudged Phil to stop refilling our glasses, but he pretended not to understand.

My mother's treble voice climbed even higher up the register. "Yes, we all thought it was the heat, but it turned out I was pregnant with you, dear!" she exclaimed to me.

"She took one look at that egg salad, and—whoops!" Daddy continued his story as if my birth were not the point. Lacking a cigar to re-enact the momentous occasion, Phil lit a cigarette and dropped the match onto the remains of his dinner.

"Lazlo doesn't let people smoke in the house," Tomas fussed.

"Who's Lazlo?" Mama asked.

"He's Julian's imaginary friend," Phil said.

"He's the violinist," I corrected, getting up to clear the plates.

"Well, Lazlo's not here, is he, now?" was Phil's reply.

Daddy chuckled. "You know, that reminds me of what Carter said—Carter's my eldest, you'd like him—one time when Pastor Ed told him he couldn't wear his peewee football uniform to church…"

I escaped to the kitchen. "Tomas," I moaned, as we scraped the salvageable leftovers into Tupperwares, "why did you let me do this? I mean, in what alternate universe would this have been a good idea?"

"Relax. Just wait till I bring out the triple-layer mocha marzipan cheesecake."

Tomas telling me to relax was the living end. "I hope so. It's like the Charge of the fucking Light Brigade out there."

Ariana, solo, stopped by the kitchen to tell us sternly that my sister was allergic to shellfish.

"You didn't warn me," Tomas reproached me.

"She's very self-conscious about it," I fibbed madly, "since my mother's people are from Louisiana." Was it the taste that upset her pregnant stomach, or the resemblance to the tiny pink creature curled inside her?

Ariana came over to take a closer look at me. "How much have you had to drink?"

"Not enough."

When we returned to the table, with Tomas bearing the cheesecake on a silver stand, Laura Sue was sitting in my seat. She and Daddy were turned toward Phil while he cheerfully answered Daddy's questions about his background. "Right now I'm a personal trainer, but someday soon I'd like to go back to school to study sports medicine."

"How about that, Laura Sue—a doctor!" Daddy actually sounded impressed.

"Not exactly," Phil demurred, "more like a physical therapist, you know, rehab for injured athletes."

"Yeah, you figure, some of those guys must get paid a bundle to shoot steroids into Deion Sanders's knee."

I listened to their love-fest with half an ear while complying with Mama's request for a photo of herself and Tomas with the cake. It was a grand specimen, decorated with a pattern of light and dark brown ripples that made me think of a ballroom floor. Tomas bragged that he had soaked the espresso beans overnight in Frangelico, and I understood why he had let me walk into this death-trap. He was a mad scientist, caring only for the elegance of his nuclear bomb.

Daddy was still attempting to find common interests for Phil and my sister. It was slow going at first, since Laura Sue was unmoved by sumo wrestling and Phil had scarcely anything to say about theories of early-childhood education, but it turned out they both favored tighter immigration controls and thought Princess Di had been treated shamefully by the Royal Family.

Ariana tucked into a large slice of cake. I ate a few bites off her plate.

"Does she like you?" I whispered.

"Your sister? Yeah, I guess. She's a nice kid."

"Good. Hold my hand."

"Someday you will pay for toying with my girlish affections."

"Please, Ari."

Fresh from her college interviews, Laura Sue was rattling off a list of her extracurriculars. Tomas passed around coffee with brandy. The guys skipped the coffee part. Ariana prepared to feed me a bite of cake. Daddy said something about going bass-fishing with Andy Crosby and asked Phil about his hobbies.

"Not much time for that," Phil said. "Basically, I get off work, I like to go home, take a hot shower, watch 'Entertainment Tonight', and get fucked up the ass by your son."

Ariana dropped the cake on my white shirt. Mama put her hand up to her mouth, that old useless gesture for keeping words in or fists out. I went around the table to my sister but she pushed her chair back and walked stiffly to the bathroom. My stomach churned, as when in dreams you approach that deadly room you always return to, where the black dog leaps out of the shadows and your mother's body is lying on the ground. That place whose furniture you recognize instantly—the crooked picture, the curtains drawn shut—which never stops you from walking back inside, makes it seem more inevitable, in fact, than waking in your own bed.

"The hell you think you are, talkin' like that to me?" Daddy bellowed. He propped himself halfway upright, his big hands spread on the table, and loomed over Phil, who squared his shoulders and jutted out his jaw. Daddy was bigger and meaner, but Phil was in better condition. Either way it wouldn't be pretty.

"Daddy—" Unsteady on my feet, I wedged myself in between them.

"You think I'm the kind of man, you can say that to my face?" Daddy continued to harangue Phil, both of them standing now. Phil said nothing; he was a noble statue, the kind the Greeks prayed to when they still thought beauty could save them from the volcano.

"Phil didn't mean anything, he was making a joke, about me," I pleaded.

"A joke? I'll tell you what's the joke." Daddy turned on me. "You and your fruity friends, inviting us to this dolls' tea party." The sweep of his arm knocked his wine glass to the floor. At the other end of the table, Ariana and Tomas were clearing Lazlo's precious dishes as fast as humanly possible. Mama cried softly into a wadded-up napkin.

"I thought you were doing so well," she wailed at me. "I thought everything was just fine."

"'Everythin' was jes' fi-ine,'" Daddy mimicked Mama's soprano drawl. "Only you would think that, Bitsy. Hell, I've known Julie was a fag ever since he cried at the Fourth of July picnic."

"I was scared of the fireworks," I said stupidly, a kid again in sweaty T-shirt and bare feet, listening for the gunshot echo after each burst of gold and silver light.

"That's not what you said," Daddy taunted. "You said you were crying because they were so byoo-tee-ful."

Phil threw the contents of his glass in Daddy's face. My sister chose this moment to return from the bathroom. Daddy's red face grew redder from the wine dripping down into his shirt collar.

"Get out, Phil! Get out!" I shoved him backward, my palm against his chest. The hurt in his eyes gave me only a moment's pause.

"Why do you have to be like them? They're never going to want you. Why do you keep doing this?"

"Just go, now!"

Daddy kicked Phil's chair over, but Phil was already at the door, out of range of his fists. Good food and drink, and twenty-five years behind the desk of Selkirk Builders, had robbed my father of the agility to pursue bigger game than women and children.

Laura Sue clung to my shoulder. She dabbed at the cake stain on my shirtfront with a wet napkin, spreading a watery brown smudge all across the breast pocket. "We'd better go," she said.

"Lulu, I'm so sorry, I don't know how this happened."

"It's always like this," she said, sounding much older than her eighteen years. "There's nothing you can do."

"Please don't let this change…your plans."

"Nothing's changed."

When Mama returned from retrieving the family's coats, I bent to kiss her cheek, but she turned aside with a tragic expression. Southern women love no-account men; every smashed glass and squandered dollar is another stitch in their martyrs' robes. In her mind she was probably already toting up the love she had wasted on her second son, starting with her fourteen hours in labor.

So at last it was only me and Tomas and Ariana with the remains of the cheesecake, like seagulls picking through a shipwreck. I washed the dishes in steaming hot water, refusing conversation. Without being asked, Tomas made up my bed on the couch. Ariana dried the dishes with a towel patterned with musical notes, which is not the sort of thing you expect a real musician to have. Maybe they were a gift from Lazlo's mother; maybe she visited once a year from Romania, dropping in unannounced with a box of honey cakes and the phone number of a nice Jewish girl he should call.

"You don't have to do that," I said to Ariana.

"I know." Putting a wineglass down perilously close to the edge of the sink, she came over and kissed me.

"You don't have to do that, either. No one's here."

"Asshole." She held me tight and I pressed my face into her warm hair, letting my tears fall, tears that had nothing to do with beauty, however much I might wish it otherwise, for both of us.